The eastern Free State is still Ace Magashule’s empire of destruction.

I’m on a trip to the original sin site of State Capture: the Estina Dairy Farm now called the Integrated Vrede Dairy Project. Here, black Free State farmers were bilked out of hundreds of millions of rands in the first incursion by the Gupta family into South Africa.

The Commission of Inquiry into State Capture confirmed that money meant for the project was laundered out of the province to pay for the 2013 Sun City Bollywood wedding of the Gupta daughter, Vega Gupta, to Aakash Jahaggarhia.

Vrede. A decade on, in the Eastern Free State, the town called ‘peace’ in Afrikaans is broken and nearly dead. It symbolises how the country has struggled to recover from the lost decade of grand corruption.

Like so many other towns in the beautiful mielie gold province, it’s also testimony to former ANC strongman and provincial premier Ace Magashule’s reign of extraction. Magashule hired the Gupta money-man Ashok Narayan as an advisor in the Premier’s Office, and a long line of bureaucrats facilitated the theft of at least R280-million from the province’s agriculture budget and its redirection to the wedding planners and as the initial deposits for the mega-state capture project.

Ten years later, as we drive through Bethlehem, Memel, and Warden off good national roads into rutted provincial routes and finally onto broken municipal roads in what were once thriving farming towns, the poem Ozymandias comes to mind, its words resonant.

Shelley wrote of corrupted legacies, and how a monument to a tyrant lay lost in the desert, its decaying inscription read: “Look on my works, ye Mighty and despair”. Shelley ends: “No thing beside remains. Round the decay of that Colossal Wreck, boundless and bare, (t)he lone and level sands stretch far away”.

The Free State is not desert, of course. It is rich mealie land, golden fields as far as the eye can see and beautiful in the ways that the central parts of our country show up. There is some gas exploration, tourism and gold mining, now reaching the end of its life. Magashule and the ANC had much to build on when apartheid ended, but the towns are now monuments to what happens when the shadow of State Capture replaces the provincial constitutional state.

Decay is visceral on the roads, making one see what happens when governments go wrong. I’ve learnt that you can feel corruption when visiting Eskom, Transnet, and other sites of capture. There is a lethargy of people and place when an institution is repurposed for taking from rather than giving in service to the country. So, it is in the Free State.

Shops are shuttered, and the economy is informalised. Hawkers’ stalls, a Boxer store, and informal hairdressing salons service people. Cash loan businesses thrive, the money secured by Sassa grant cards, show how the grants economy keeps many rural towns limping along. The tractor seller is the most prosperous business.

It was supposed to be different after 30 years of cross-funding of provinces by the National Treasury, which runs an economy still classified as middle-income, which means quite wealthy. With relatively high taxes for a developing country, this cross-subsidisation should have meant that the Free State government would have done much more to maintain the economy and improve employment and opportunity. The gap between the funding and the reality on the ground is corruption.

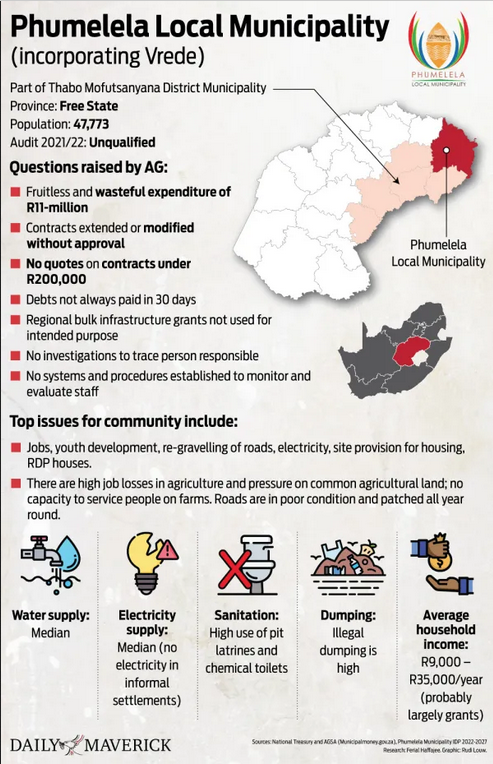

Thembalihle, the dirt-poor township of Vrede, remains a stubborn apartheid spatial distance from the centre when good governance could have mediated the gap. The auditor general’s numbers tell the story. The development gaps are yawning and getting wider. Instead of rising prosperity, there is increasing poverty.

When I completed my book Days of Zondo—The Fight for Freedom from Corruption, I searched for light at the end of our dark tunnel. And found it, I thought.

“In January 2022, (Ephraim Makhosini) Dhlamini and the other beneficiaries were finally given what was rightly theirs when the Free State handed over the Vrede Dairy Project to them, in one of the small victories against State Capture,” I reported.

In April 2024, I’m in Vrede to see what happens when State Capture is caught, bound and reportedly ended. The Vrede Integrated Dairy Project’s grand brick entrance is familiar. This is because journalists beat a hot trail there to hear the stories of Dhlamini and other farmers. They were told by then Agriculture MEC Mosebenzi Zwane (who would later become the Gupta point man as Mines Minister) to sell their cattle. “The locals were taken for a ride,” the State Capture Commission report found. “They were duped Nonqawuse-style, and persuaded to sell their cattle on the basis that the government would donate dairy cows to them…”. The local farmers didn’t get the cows and were only ever the on-paper owners of Estina.

The beneficiaries are still fighting for what’s theirs; they remain only the on-paper owners of the Phumelela Integrated Farming Trust, the name of the new project. It received R18.9-million from the provincial government and generated R5.6-million in 2023. This is an alarming return on a public investment now well north of R280-million. In 2023, the 61 beneficiary farmers received a gift card of R1,300 and a 5kg meat parcel from the slaughter of two cattle, according to answers in the provincial legislature earlier in 2024.

Terence Maela, who manages the farm on behalf of the trust, said he had inherited a limping operation with animals in poor health.

The operation of 202 cows started producing 1,000 litres of milk a day and is up to 4,000 litres now. “There are black farmers who can do things. I trust myself. We have arrived,” Maela told EWN in this interview.

Maela is trying his best, and Premier Mxolisi Dukwana has also attempted to close the corruption taps. He blew the whistle on Magashule and gave necessary evidence before the State Capture Commission.

A dairy farmer who did not want to be named and who works with emerging farms of a similar size says the Vrede farm is underproducing. Dairy farming has moved to the Eastern seaboard, he says, and feed-lot farming is more expensive. Dairy farming in Vrede is like pitting a Lesotho pony against a racehorse. We visited the farm on the Easter weekend, when the entire country goes on holiday, and it was empty but for the cows and a single foreman. The expensive machinery was quiet.

“A dairy farm doesn’t shut down and go to sleep. It has to be fully staffed every day. It’s like being a nurse or a police officer. You’re always on,” says the dairy farmer, which suggests it is not being optimally run.

The Guptas, who despatched unqualified underlings to run Estina, caused ruin and devastation. They knew nothing about dairy farming. Maela knows a lot, but more is needed to even consider paying the beneficiaries the dividends they say are their due.

AmaBhungane reported over the years that animals have died, and money has been siphoned into the Free State tender machine. The animals look healthier now, but the farm is still a cost centre rather than a profit centre to improve the lives of the first known victims of the state capture years.

“Almost every town is like this. There are no opportunities, and young people are not working. These are grant-based economies. Of 2.9 million people, one million are on social grants,” says the province’s DA Free State leader, Roy Jankielsohn. Like many rural towns, maintenance in Vrede is done by local work crews supported by local businesses. “They are proud of their towns,” he says.

Jankielsohn has calculated the cost of the dairy project at R7.3-million per beneficiary. Even if government had given each person a fraction of that amount, it would be much more than a gift card and a meat hamper to make up for their lost cattle.

When you go through the auditor-general reports for the Free State municipalities, wasteful expenditure runs to the billions of rands each year. Budgets of this size, if wisely used, should have catalytic growth effects on provincial economies.

Ace Magashule’s posters festoon poles across the province as he contests the elections under the banner of his start-up, the African Congress for Transformation. In his stump punt, Magashule’s legacy in the Free State is of a thriving place which still needs him.

The story of the Free State’s towns tells a different tale. The State Capture Commission recommended investigations with a view to prosecution for Magashule, the Ozymandias of the province. He is about as far from jail as Mars is from the moon as the National Prosecuting Authority has struggled to mount effective prosecutions in the Free State.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!