Minister Gwede Mantashe commissions the first significant seismic survey in 50 years in the pursuit of natural gas and petroleum.

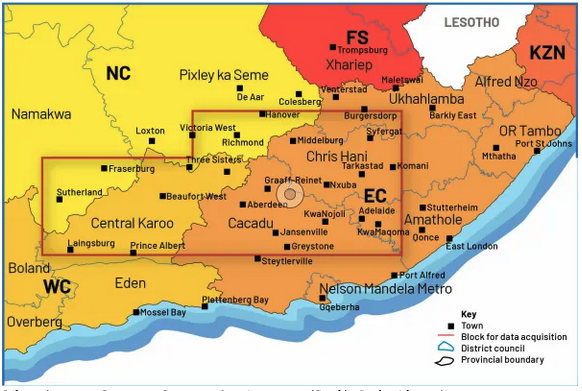

For the first time since the 1970s, the south-central Karoo Basin – a vast region that stretches from the Northern Cape, across the Western Cape and into the Eastern Cape – will be subjected to large-scale land seismic and airborne surveys to explore for oil and gas that may lie below the ground.

On 30 August, Mineral and Petroleum Resources Minister Gwede Mantashe published a Government Gazette inviting written comments on his intention to investigate the subsurface geology of this region. The surveys aim to assess geological risks and examine whether there are enough resources to justify extraction.

In essence, Mantashe wants to know if the Karoo Basin holds commercially viable oil and gas reserves. If they exist, the discovery could pave the way for local oil production, potentially reducing fuel prices and diversifying South Africa’s energy mix.

But it could also mean fracking – an extraction measure that is water intensive and may be environmentally harmful if improperly implemented – which communities in the Karoo, a known water-scarce area, are deeply concerned about.

The Department of Mineral and Petroleum Resources (DMPR) told Daily Maverick that the investigation will start as soon as the Environmental Impact Assessment has been completed, which is estimated to take six months from November 2024.

“If we want to know if we have any resources at all that could be brought into production, we won’t know until we’ve drilled holes and we won’t know where to drill the holes until we’ve done some geophysical surveys,” said Dr Raymond Durrheim, geosciences professor at Wits University and previous South African Research Chair in Exploration, Earthquake and Mining Seismology.

“Otherwise, you’ve just got no idea what wealth we might or might not have – there might be opportunities that we are missing.”

Geophysical surveys

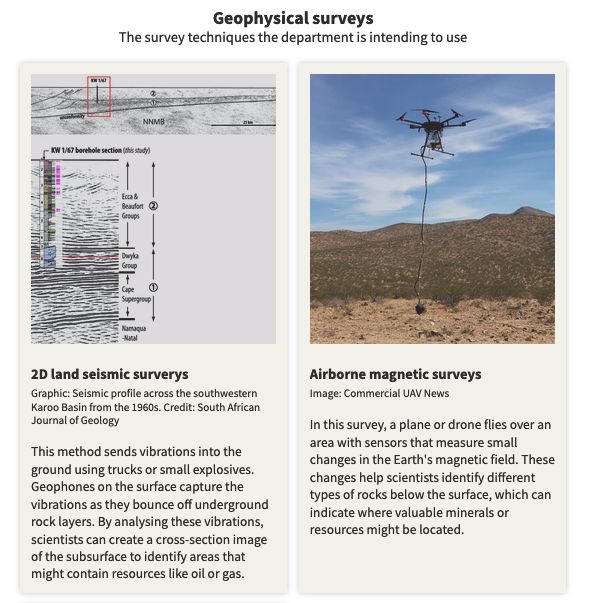

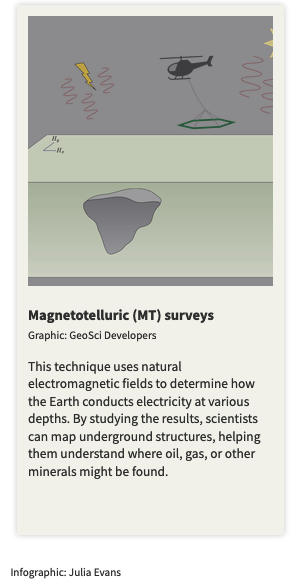

To investigate the oil and gas potential, the DMPR plans to use 2-D seismic data profiling, airborne magnetic surveys and magnetotelluric surveys. These techniques don’t require digging deep into the ground; instead, they rely on measurements taken from the surface to create detailed maps of what lies beneath.

Limited environmental disturbance

Durrheim explained that if land seismic surveys are carefully planned and well executed, you can minimise the negative impact on the environment.

For instance, the vibrations and movement of equipment used in 2D land seismic surveys (like a heavy metal pad under the weight of a truck) can disturb local vegetation and wildlife, especially in sensitive ecosystems (of which the Karoo is). But the impact is typically temporary and can be minimised with careful planning.

The DMPR said the seismic survey, “is intended to be done in a responsible manner without disturbance to land and infrastructure. Any impact on people during operations is expected to be minimal to nil.”

As these initial surveys can have a limited environmental impact if well planned, even some Karoo communities are open to getting more geological data of the area.

“We want credible research to be done to augment the state of knowledge, including the subsurface geology of the Karoo and the potential risks associated with this sort of development,” said Derek Light, an attorney from Graaff-Reinet who represents hundreds of landowners in the proposed area in the Karoo.

“The manner in which it’s being done is, however, of concern, because of its limited publication, vague nature and the fact that it’s limited to calling upon landowners in the subject area to comment,” added Light, who also represents AgriSA and its provincial affiliates in the affected area.

Does this mean fracking?

If enough oil and gas reserves are found, extraction would likely involve fracking (hydraulic fracturing), which raises social and environmental concerns. Unlike conventional gas, the Karoo Basin’s shale gas is trapped in tightly packed rock, located 1km to 4km below the surface, and requires high-pressure liquid injection to crack the rock and release the gas.

The exact reserves are still unknown, which is why seismic surveys are crucial. While concerns about fracking remain, it’s the only viable method for extracting shale gas, and development could take decades if resources are found.

Durrheim explained that there has been desktop assessment and a few holes drilled in the region since the last time seismic surveys were done in the 1960s and 1970s.

“Essentially, we have to repeat the exercise,” he explained, “the difference is that we now have a different target – i.e. oil and gas in the shale source rock rather than oil and gas in a sandstone reservoir, and have much better seismic surveying technology.

“At this point, we really don’t know [what reserves we have],” said Durrheim. “Until we drill a few holes, hopefully in the best spots that have been identified by geophysicists, it’s all speculation.”

Pros and cons of fracking for gas

The CSIR put together a Scientific Assessment of the Positive and Negative Consequences of Shale Gas Development in the Central Karoo in 2016.

Light noted that this assessment was done by more than 200 specialists (including Durrheim) and was internationally peer reviewed.

“They all found that there were limits of knowledge that needed to be augmented by further research, that there was limited decision making and that there was a need to develop proper regulation,” said Light.

“That report confirmed that our concerns were real.”

Environmental impact

Water

Shale gas development requires large amounts of water, a scarce resource in the Karoo region, which already faces water stress and over-allocation.

“Here in the Karoo, we’ve got over 90 towns, most of which rely on underground water sources,” Jonathan Deal, prominent Karoo environmentalist and founder of the Treasure Karoo Action Group told Daily Maverick. “If one of those aquifers on a farm, or adjoining a town or a settlement, is polluted [from fracking], there is no plan B for water – it’s finished.”

Biodiversity

The Karoo is a biodiversity hotspot, home to unique and sensitive ecosystems that could be fragmented by gas development. The CSIR report recommended that efforts to mitigate environmental damage should focus on a landscape-level approach to conservation, rather than focusing solely on physically disturbed areas.

Air quality and greenhouse gases

While shale gas is often touted as a cleaner alternative to coal, the CSIR assessment noted that its impact on greenhouse gas emissions depends heavily on methane leakage during production and transportation. Uncontrolled leaks could negate or even reverse the potential benefits of reduced carbon dioxide emissions.

Jobs

The CSIR assessment acknowledges the potential shale gas development has to create jobs in the Karoo region. If a significant amount of gas was found, they estimate that it could lead to 2,500 direct operational jobs in drilling, trucking and power generation – with residents of the study area probably able to fill 15% to 35% of these positions, increasing over time as training proceeds.

However, many of these jobs may be temporary, tied to the exploration and production phases, which could last anywhere from a few years to a few decades.

Economic impact

Benefits

The assessment acknowledges that shale development could boost the local and national economies through job creation, increased tax revenues and reduced reliance on imported energy.

The discovery of commercially viable shale gas reserves could also attract foreign investment and contribute to economic growth.

South Africa’s national oil company, PetroSA, already invests in oil in Mozambique, Nigeria and Sudan, and elsewhere in the world. Producing it locally could add local economic benefit.

Risks

Shale gas development comes with economic risks, especially the “boom and bust” cycle typical of extractive industries. If not carefully managed, rapid growth can drive up inflation, widen inequality, and harm other key sectors like agriculture and tourism. To ensure long-term economic stability, experts from the assessment say it’s crucial to plan ahead, invest in diversifying the local economy and make sure the benefits are shared fairly.

Energy

Key energy strategies, like the National Development Plan 2030 and the Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) recognise natural gas as important in the transition towards more sustainable energy. And Mantashe’s 2024 draft Gas Master Plan notes that shale gas development in the Karoo would make South Africa “… a net exporter of natural gas with significant economic benefits”.

Read more: Mantashe’s Gas Master Plan scant on key details such as finance

However, the viability of shale gas extraction remains uncertain, and the CSIR assessment advises that the potential benefits, such as job creation and improved trade balance, must be weighed against risks, including water resource depletion, biodiversity threats and infrastructure challenges in the Karoo region.

Ongoing community concerns

For communities in the Karoo, the debate over shale gas development has been ongoing for more than a decade. Light explained that his community’s opposition to shale gas exploration, which began in 2009, led to a moratorium on petroleum resource exploration in the Karoo in 2011. They also secured a court ruling that prevents hydraulic fracturing (fracking) until proper regulations are established.

Their concerns include a lack of understanding of the Karoo’s subsurface geology and groundwater structures, which could be impacted by such development.

As such, Light agreed that an investigation into the subsurface geology of the region, “is not a bad thing”.

But their concerns about the lack of proper regulation to control shale gas development remain.

Deal agreed, saying, “If it comes to pass that they find reserves, and they get through financial barriers, the concerns for me remain that the government has proven itself completely unable to monitor and enforce the standards of mining activity.”

Ultimately though, Light said that, “the body of people we represent remains opposed to shale gas development utilising hydraulic fracturing – but at the very least, we have to ensure that the state of knowledge is such that a proper assessment of the risks and benefits can be made. And if it were ever to proceed, that it is properly regulated.”

Light is developing the community’s response, which is due at the end of September.

Durrheim reflected: “People tend to forget fracking is only a relatively small process in the long chain from exploring, producing, transporting, refining, distributing and using petroleum.

“In my opinion, one of the main reasons for the opposition to fracking is that it has brought production close to communities that used to enjoy the benefits of petroleum, but didn’t incur social and environmental costs.”

The bigger picture

The African Union sees fossil fuels playing a crucial role in expanding African economies and energy access. However, climate science has shown that we have already run out of our carbon budget.

As Cormac Cullinan, environmental attorney, told Daily Maverick, “only a fraction of proven fossil fuels reserves can be burnt without triggering catastrophic impacts for Africa”.

The International Energy Agency has reiterated that we can’t afford any more fossil fuel expansion, and governments must stop approving new fossil fuel projects if we have any chance of restricting global warming between 1.5°C and 2°C since pre-industrial levels – after which, every fraction of a degree is likely to increase the burden of human suffering and the likelihood of tipping points.

“What is the point of spending lots of money and time exploring for oil and gas that we cannot use without causing terrible and irreversible harm?”

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!