In a recent public lecture on ‘The State of the Namibian Economy’, an eminent economist opined that at the heart of the problem lies the issue of policy.

Indeed, public policy matters: It is at the crossroads of ideas, values, envisioning, agency and resource allocation.

The speaker did not provide a full explanation for why this is so. The reasons for this are multiple and complex.

META-ANALYSIS

Any serious analysis of public policy and of politics demands meta-analysis. While there is a cabinet-endorsed template for policy that sets out the structure of policies, in meta-analysis we need to consider the ideas, methods and approaches to and the political grammar which it employs.

Based on my experience of policy design for government, it is evident that precious little thinking and meta-analysis go into policy design.

Many of the public policies are ‘cut-and-paste’ exercises, based on policies of other contexts and/or from international organisations and foreign consultants.

Meta-analysis is research-led and starts with a definition of the problem as public policy is intrinsically problem-oriented.

Once the problem has been adequately understood through public deliberation and credible research, meta-analysis proceeds to ask and truthfully answer, the following set of interrelated questions.

These may usefully be called the six ‘Is’. Collectively, they function as the toolkit for policy design and review.

– Information and Interests: The first ‘I’ refers to the information needed for and of policy. Do we have adequate credible information/data for and of existing policy?

The second ‘I’ is a definition of the interests.

In whose interest will the public policy work – how is the ‘public’ constituted?

Which interests are key or strategic? Subsidiary? Short, medium and long-term?

How do such interests relate to the wider notion of the ‘national Interest’; at best a contested and dynamic construct.

– Ideas or Ideology: The third ‘I’ refers to the Ideas or ideology that inform policy.

Are public policies preeminently ‘neo-liberal’? Market-based and related? Social-democratic? Socialist? Populist?

On what grounds do we privilege one ideology over another? Because, depending on the policy domain, governments often take contradictory ideological stances.

– Capacity and Impact: The fourth ‘I’ refers to the institutions and their capacities needed to craft, implement, monitor and review policy.

The fifth ‘I’ refers to the information flow and sharing required for decision-making and meaningful policy review.

The final ‘I’ refers to the differential impacts the policy is meant to have.

Such impacts must include delivery analysis, fiscal and social sustainability, governance and ethical considerations.

Meta-analysis rarely features.

The specific issue-, programme-, multi-programme and strategic analyses are often not done by harnessing a combination of techniques, notably: Cost benefit analysis, economic forecasting, financial planning, scenario generation, operational research, systems analysis, social indicators and impact assessment.

THE NATURE OF THE STATE

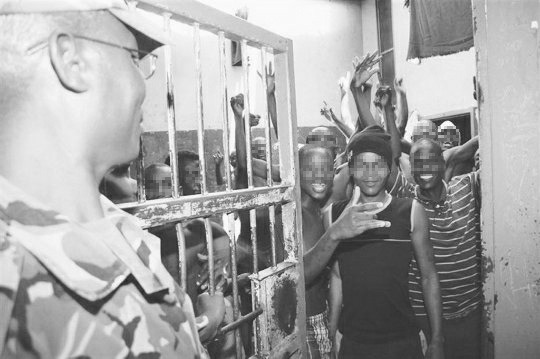

An equally important second reason why Namibia experiences policy failure, or has lacunae (gaps) in policy, relates to the nature of the state and its appropriated political practices.

Truth be told, Namibia has yet to develop both a policy- and a strategic culture.

Consequently, policy coherence is often low, interconnections across cognate policy domains are largely absent, ownership on the part of those expected to design and implement policy is rare.

More worrying, is the confluence between the governing party, government and the state.

Such a confluence not only compromises the values of transparency and accountability but creates frozen knowledge that can become dictatorial.

A structural condition that sustains the production and reproduction of knowledge developed in contexts different from the present, often with a clear bias towards the maintenance of public power through the reciprocal assimilation of elites.

There is simply not enough innovation and creative thinking in policy design.

While civil society does have some impact on public policy design, it hardly features in policy monitoring and evaluation.

The civic arena is affected by factional competition, the uneven presence of the state in parts of the country, and the ‘politics of the belly’.

Political networks of patronage kill meritocracy in public representation.

Small wonder, public policy is not seen as the crossroads of ideas, capabilities, resources and real empowerment.

- • André du Pisani is emeritus professor of politics at the University of Namibia (Unam)

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!