IN December 1977, a meeting that would change the history of southern Africa took place at the seaside holiday house of South African prime minister John Vorster.

It was at that meeting with his defence advisers that Vorster made a watershed decision to step up military and political action against Swapo, which in the mid-1960s had launched an armed struggle aimed at ending South African control over the then-South West Africa.

The upshot of that meeting, of which the minutes were declassified more than 20 years later, was that it was decided that the South African military would no longer be fighting an essentially defensive war against the People’s Liberation Army of Namibia (Plan), but would embark on pre-emptive attacks against Plan forces. That meant that the conflict between Plan and the South African military was to be expanded into Angola.

The devastating attack on Cassinga on 4 May 1978 was one of the most immediate consequences of the decision taken at that meeting.

What also followed was more than a decade of escalating warfare against a Cold War backdrop. The South African military would end up clashing in battle not only with Swapo’s Plan fighters, but also the Angolan armed forces and their Cuban allies, assisted by the Soviet Union, and simultaneously would be providing crucial support to Unita, fighting a bitter civil war against Angola’s MPLA government that would still continue for years after the South African Defence Force had left Angola and Namibia had made a mostly peaceful transition to independence.

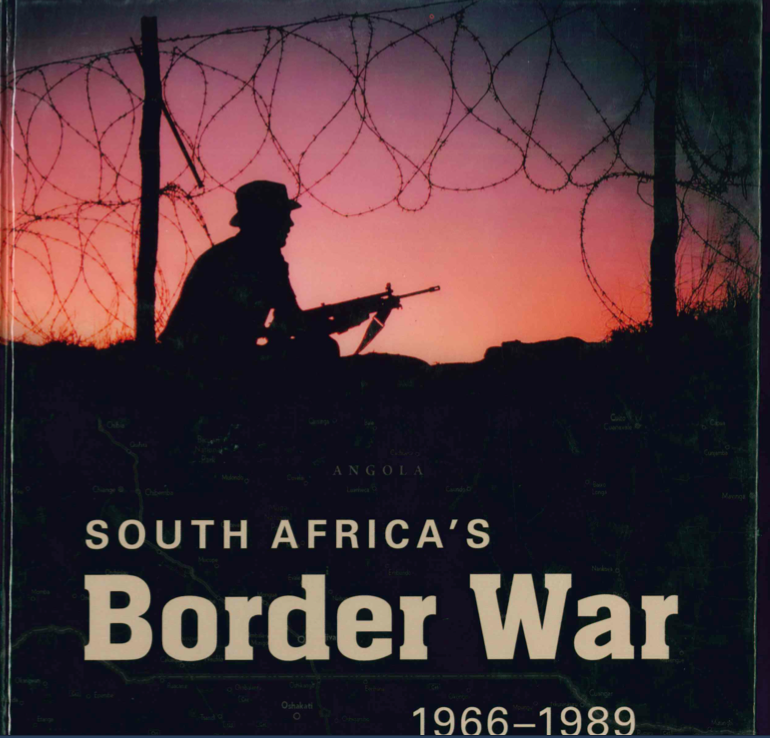

Author Willem Steenkamp recounts the secret December 1977 meeting at Vorster’s holiday house in the new edition of ‘South Africa’s Border War’ – his account of the military conflicts that stemmed from South African rule over Namibia.

Having been out of print for many years since it was first published in 1989, ‘South Africa’s Border War’ has been updated and appears in a new edition under the banner of the South African publishing house Tafelberg.

It is a detailed account of a turbulent period in the history of southern Africa – but in the absence of key voices, specifically from the Swapo and Plan side of the war, it is not a definitive account.

Over some 330 pages, richly illustrated with photographs, Steenkamp gives a year-by-year account of the launch of Swapo’s armed struggle against South African rule in Namibia in 1965/66 and South Africa’s response to that pivotal development, the South African military’s invasion of Angola in 1975 in reaction to the collapse of Portuguese rule in that country, and then the steady escalation of the conflict in northern Namibia and Angola over the almost 15 years that followed.

Eventually, by 1988/89, it was to end in a negotiated settlement which Steenkamp argues was a result that delivered to the main players what each of them ultimately wanted: Swapo won independence for Namibia, and South Africa secured a multi-party democracy that was not under communist influence in Namibia.

In his view, the real losers in the struggle were probably the Cubans and the Soviet Union.

Much bloodshed preceded those results, though. And although Steenkamp cites casualty figures for each year that the war dragged on, a proper record of the toll the war took on the foot soldiers on both sides and on the civilian population in especially northern Namibia is absent. Human human rights abuses that were committed during the course of the conflict are acknowledged only in passing, for example.

The yearly and lopsided death tolls recorded by Steenkamp give an indication of the heavy price in human lives paid. For instance, in 1980 the South African security forces recorded a fatality figure of 100 in its own ranks, compared to 1 447 Plan combatants claimed killed; in 1981 the SA military had 56 fatalities and claimed to have confirmed having killed 1 479 Plan combatants; in 1982 the death tolls were 77 on the South African side and 1 286 on the Swapo/Plan side.

As detailed and well-illustrated as ‘South Africa’s Border War’ is – although more maps would have helped the reader to better navigate the battle grounds on which the war was waged – this is not the complete history of the decades of conflict in southern Africa that preceded Namibia’s attainment of independence in 1990. It is a South African perspective of that history – something that Steenkamp acknowledges early, in his foreword – and therein lies the main qualm the Namibian reader would probably have with this publication.

Often, as Steenkamp describes the operations of the South African Defence Force and its top brass, one is also left wondering what the thinking was on the other side of the conflict. What were the Plan commanders thinking and planning at that stage? Faced by the formidable military might that the SADF was, what were the strategies of the Plan high command at that point?

Some individual combatants on the Swapo and Plan side of the war have recorded their experiences in print, but the top commanders of Plan and historians are yet to give full written accounts of Plan’s conduct of the armed struggle.

In the absence of the necessary Namibian balance, something like photographer John Liebenberg and historian Patricia Hayes’ excellent and evocative photographic collection ‘Bush of Ghosts’ (2010) would be a fitting neighbour of ‘South Africa’s Border War’ on the bookshelf.

Namibia has now been independent and at peace for longer than the 23 years that the border war lasted. The truly Namibian history of the war should have been written by now.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!