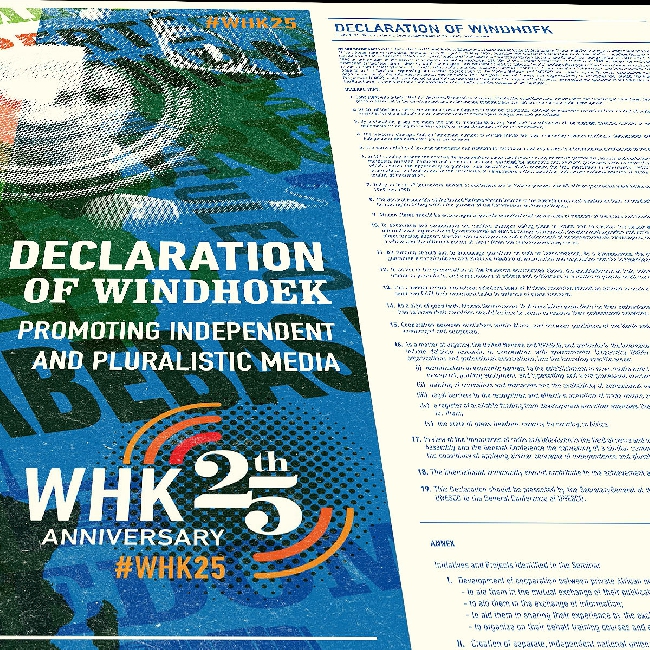

All too often declarations remain just that: declarations, pieces of paper filed away and forgotten. Not so with the Declaration of Windhoek on ‘Promoting an Independent and Pluralistic African Press’ adopted on 3 May 1991, says HENRY MAINA.

The timing was perfect. The winds of change were blowing for a second time after the liberation from colonial rule in the 1960s as many countries in Africa embarked on a democratisation process leading to the end of military and one party regimes.

Up until then, independent professional journalism was a rarity and efforts to entrench it came at a huge price. African journalism, in its various manifestations, has largely been worshipful and reverential of authority, primarily as a means of self protection and remaining economically viable.

But the situation has been changing fast, not least thanks to the Windhoek Declaration. In the new spirit of democratisation, the Declaration contributed directly and indirectly to changing the media landscape in Africa.

In essence, the gathering in Windhoek marked the beginning of a solidarity movement of journalists, editors and media owners and the emergence of media development organisations across the continent.

The Media Institute of Southern Africa (Misa), an organisation with chapters in 11 countries of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and which promotes independent and pluralistic media, was formed in 1992.

One of its first projects was the establishment of an email alert system to make Africa and the rest of the world aware of violations of media freedom as soon as they occurred – much to the surprise and anger of governments which, up to that stage, had been able to act against journalists without much international attention. Regular conferences were held to share experiences in setting up and maintaining newspapers against all odds.

Following in the footsteps of Misa, similar organisations were initiated in Eastern and West Africa with mixed levels of success. The Media Foundation for West Africa has emerged as a strong sub regional actor on media freedom advocacy.

The Media Institute of Kenya and the East African Media Institute took off but became moribund not long after their infancy.

Discussions on forming a global coalition started at the Windhoek conference and the International Freedom of Expression Exchange (Ifex) was established a year later. Ifex is now a worldwide actor on freedom of expression.

The Declaration gained global relevance at Unesco’s General Conference in 1991 when a resolution ‘recognised’ that ‘a free, pluralist and independent press is an essential component of any democratic society’.

The conference described the Declaration as ‘a catalyst in the process of encouraging press freedom, independence and pluralism in Africa’ and resolved to ‘extend’ such declarations ‘to other regions of the world’.

It also recommended to the United Nations General Assembly that 3 May be declared ‘International Press Freedom Day’. The UN did so in 1993.

Since then, 3 May is a date observed every year to celebrate the fundamental principles of press freedom, to evaluate press freedom around the world, to defend the media from attacks on their independence, and to pay tribute to journalists who have lost their lives in the exercise of their profession.

While Unesco leads the worldwide celebrations by identifying the global theme and organising the main event in different parts of the world each year, many parallel national celebrations are also conducted.

The Declaration left its impact around the globe in other ways as well. In 1992, a Unesco conference of media practitioners held in Kazakhstan adopted the Declaration of Alma Alta, declaring ‘full support for, and total commitment to, the fundamental principles of the Declaration of Windhoek’, and acknowledging ‘its importance as a milestone in the struggle for free, independent and pluralistic print and broadcast media in all regions of the world’.

The Declaration of Santiago (Chile), which followed in 1994, expressed the same support.

Two years later the Declaration of Sana’a (Yemen) stated that, in line with the Windhoek Declaration, the ‘establishment of truly independent, representative associations, syndicates or trade unions of journalists, and associations of editors and publishers is a matter of priority’. Finally, in 1997, the Declaration of Sofia (Bulgaria) urged ‘all parties concerned that the principles enshrined in this (Windhoek) Declaration be applied in practice’.

Celebrations on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of the Declaration – also held in Windhoek – were used by activists to propose and adopt a new document that would address issues specific to broadcasting, the African Charter on Broadcasting. The Charter proposes a three tier system of public, commercial and community broadcasting.

The worldwide recognition of the Windhoek Declaration and the solidarity of African journalists made it possible to use both documents as powerful lobbying tools.

They kick started the liberalisation of media laws in Africa and encouraged many journalists to start independent newspapers, for example The Post in Zambia in 1991, MediaFax in Mozambique in 1992 and The Monitor in Malawi in the same year.

The demand for truly public broadcasters has become a common call around the continent – although with mixed success so far. Community radio stations are flourishing in many countries – even though many struggle financially.

Like the African Charter on Broadcasting, the AU’s Declaration recognises the three tier system and demands that ‘all state and government controlled broadcasters should be transformed into public service broadcasters’.

The Windhoek Declaration also informed the Midrand Declaration on Press Freedom in Africa, adopted by the Pan African Parliament in 2013, as well as the Midrand Call to Action on Media Freedom in Africa, also adopted by the PAP in the same year.

Twenty five years after Windhoek, there has been some progress with regard to media freedom in most African countries and the lofty goal features prominently in many an official speech. However, an ‘independent, pluralistic and free press’, as the Declaration demanded, is still far from being a matter of course.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!