In late 1907, the 38-year-old Rudolf Pöch set off on a salvage expedition to collect as much material as possible about people he called “Bushmen”, who he, like many of his colleagues, believed were on the verge of extinction.

Pöch was not some amateur collector, having spent 1904 to 1906 doing research in German New Guinea.

Generously funded by the Imperial Academy of Sciences in Vienna, his expedition featured state-of-the-art equipment, including at least three cameras, two phonograph recording devices and a movie camera.

Assisted by the German military, he travelled to Gobabis and Rietfontein, collecting and measuring bodies.

From Namibia he headed to Bechuanaland and then south to the Cape Colony, covering some 2 600 kilometres and returning to Austria in 1909 with what contemporaries described as a magnificent collection consisting of copious notes and diaries, more than 15 000 artefacts, some 2 000 photographs, 80 skeletons, 150 skulls and the corpses of a San couple preserved in a barrel of salt, plus more than 30 minutes of movie and a number of phonograph recordings.

These recordings are the focus of Anette Hoffmann’s ‘Listening to Colonial History: Echoes of Coercive Knowledge Production in Historical Sound Recordings from Southern Africa’ (Basler Afrika Bibliographien, 2023).

A much-viewed short video entitled ‘Bushman speaking into the phonograph’, based on a film he made and later synchronised with sound, has been hailed as the first ethnographic film with synchronised sound. Pöch is lauded as one of the founders of Austrian anthropology and has been the subject of a number of books and articles, including an insightful hour-long documentary film produced in 1992 by Andrea Gschwendtner called ‘Der Menschenforscher’ and available as ‘The Anthropologist’ with English subtitles.

Enter Hoffmann, who has done extensive field research in Namibia and is a foremost audio historian. Her concern is with how colonial knowledge is coercively produced and archived and this short book makes for compelling reading. Originally published in German, Basler Afrika Bibliografien is to be congratulated for producing a highly readable, inexpensive translation.

For the more theoretically inclined, the first two chapters on the nature of the colonial archive and how it straitjackets and smothers the voices of the colonised and the subalterns will be of interest, but the general reader will undoubtedly be beguiled by the second half of the book, which features Pöch at work and where Hoffmann demonstrates how close listening to the recordings not only for their sounds but also for their silences, and a deep reading of Pöch’s writings coupled to a wider socio-historical contextualisation can generate fresh insights and upend conventional scholarly wisdom.

These recordings are readily available on the web and the book conveniently supplies a list of web addresses for readers who might wish to access them.

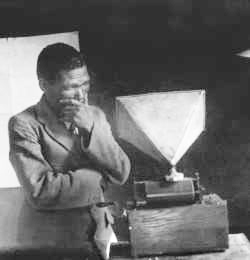

man from southern Namibia listens

to a sound recording, 1931.

Photo: Hans Lichtenecker, Archives

Basler Afrika Bibliographien

Hoffmann focuses on two sets of recordings. The first deals with a person called young |Kxara, Pöch’s factotum, ‘fixer’, gatekeeper and interpreter. But, surprise, surprise, the recording features Pöch in a rant displaying all his prejudices and fears using a mixture of hardly comprehensible languages, and completely throws his linguistic competence into doubt.

But it is the second set featuring the ‘older’ |Kxara, now accompanied by fresh translations by Job Morris, a Naro-speaking activist, which is the final push that undermines Pöch’s scholarly edifice as |Kxara subversively admonishes Pöch for his stinginess and lack of sharing.

Much contemporary research now suggests that the bedrock of San society is not “primitive affluence” – the belief that they do not have to work hard to satisfy their needs – but conviviality or sharing.

One reason the movie ‘The Gods Must be Crazy’ is so popular at Tsumkwe is said to be that in some of the scenes the star, N!xau ‡Toma, complains in Ju/’hoan about the inane repetitions the film’s producer and director, Jamie Uys, insists upon, to the latter’s obliviousness.

Those labelled “Bushmen” made their lives not only against but also within colonialism, as Hoffmann reveals the ambiguities and paradoxes which unsettle the neat categorisations of the colonial archive.

But Pöch was not exceptional. Starting with Galton’s ‘The Art of Travel’ (still in press!), scientific collecting guidebooks for use in the global South were intrinsically coercive and exemplars for demonstrating masculinity.

Pöch’s corpus has one merit: It is so comprehensive that this alternative analysis so admirably done skewering Pöch’s scholarly sanctimoniousness is possible.

So, a minor quibble: as Geertz famously commented: “All ethnography is part philosophy and a good deal of the rest is confession.” Maybe some confession would enable readers in future generations to undertake a ‘deep’ reading of this book?

– Robert Gordon is an anthropologist whose publications include ‘Mines, Migrants and Masters: Life in a Namibian Compound’ (1977), ‘The Bushman Myth and the Making of a Namibian Underclass’ (1992), ‘Picturing Bushmen – The Denver African Expedition of 1925’ (1997) and ‘Ethnologists in Camouflage’ (2022).

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!