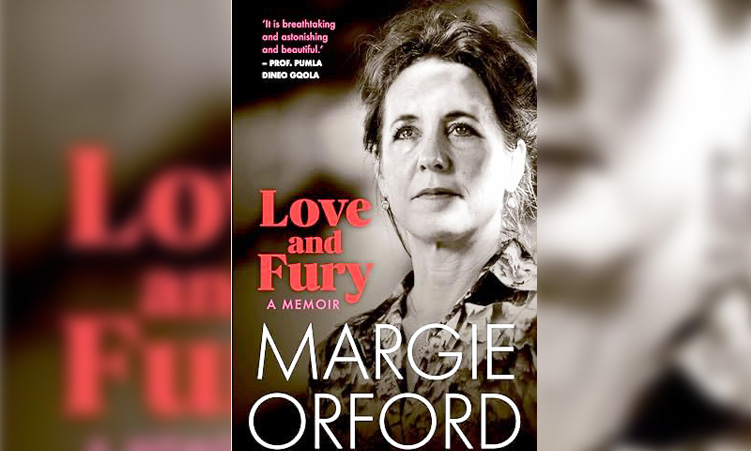

Some books can give you insights you never knew you needed or wanted.

‘Love and Fury’ by Margie Orford is one such book.

Writing one’s story can be a means of catharsis, a way of healing and dealing with traumatic experiences.

As Orford ironically puts it: “This book kept me alive; I will give it that.”

Home, exile and the liberation struggle have been the key themes in Namibian autobiographies.

However, while the desire for freedom is the focus in Orford’s memoir, it is personal freedom she yearns for.

This memoir is brutally honest and disturbing. It is often philosophical and always articulate.

Orford was born in London, raised in Namibia, got married in London to her South African partner, became the mother of three daughters, was educated in South Africa, studied in New York for her master’s degree and in the United Kingdom for her doctorate, got divorced 25 years later, and now lives in London with her new husband.

This memoir gives the story behind her Clare Hart novels (and the exhaustive research behind them) for which she has been hailed as the queen of South African crime fiction.

But it also tells the story of her writing career, of a marriage (her parents’ and her own first marriage), of her close relationship to her sister Melle, of sexual abuse, and of her constant battle with severe depression.

A major theme is the author’s “almost killing” and impossible challenge of balancing her role as a wife and mother with her relentless desire to write.

“Mind or body – that was the choice, because I did not know how to inhabit the middle ground,” she writes on page 19.

“Writing and sex, creativity and love should be entwined, but I did not yet know how to weave them together. It felt then as if it had to be one at the expense of the other: writing or sex, creativity or love,” she writes.

This ongoing conflict between the two roles will resonate with many of her women readers.

PATRIARCHY EXAMINED

Orford frequently suffered migraines and insomnia, and was often suicidal. She is a feminist and subjects patriarchy in southern Africa and marriage to rigorous examination.

“Marriage is an institution in which, generation after generation, women are forged. That is both sanctuary and prison […] marriage can be a place where loneliness hides in plain sight”. (p4)

She sees the high number of violent crimes against women in southern Africa as being rooted in the patriarchal mindset of most men, and took the time to investigate the violence as essential research for the writing of her Clare Hart crime fiction series – one of which, ‘Blood Rose’ (2007), is set at Walvis Bay – in which the protagonist is a woman detective.

“The terrorisation of women seemed central to the construction of male identity. The attacks I knew about were so excessive it seemed the intent was not only to kill the woman, but also to obliterate her body.

“ As if the assailants were driven by an endless internal rage at women, which was […] a rage at the vulnerability women represent in patriarchal society.” (p.144)

Many other topics interlink and recur throughout the memoir – family life and its challenges, driving ambition, writing, anger, identity, love, restlessness and rootlessness, divorce and the toll it takes, pervasive violence, sexual abuse, deep depression and mental illness.

Despite these mostly negative sub-themes the book makes for an insightful and informative read.

This is mainly due to the author’s writing style, which includes the use of humour, intertextuality, irony, imagery and natural dialogue.

The characters come to life as does the author herself in all her complexity.

The structure of the memoir aids the reader, since instead of long chapters in chronological order, the author uses flashbacks together with short chapters and location to divide her text.

The role of place is significant – with five of the six sections given the names of cities or countries.

There is rarely a feeling of the author being ‘at home’.

She is usually on the move and “In Transit” – hence the title of one section.

This heading speaks to the restlessness and constant need for movement of the author, which can be interpreted as a form of escape.

What links me to this author, apart from our love of literature, is firstly that we shared an office for some months at the University of Namibia, when we both were teaching in the English department in the mid-1990s, and secondly that we both worked with male inmates, which gave us huge insight into a different world and men’s mindset.

Orford gave weekly lessons in writing to prisoners in Franschhoek prison over a year from which a book emerged (‘Fifteen Men: Words and Images from Behind Bars’, 2008), while I co-facilitated workshops in alternatives to violence at Rundu and in Windhoek over several years.

‘Love and Fury’ is published by Jonathan Ball.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!