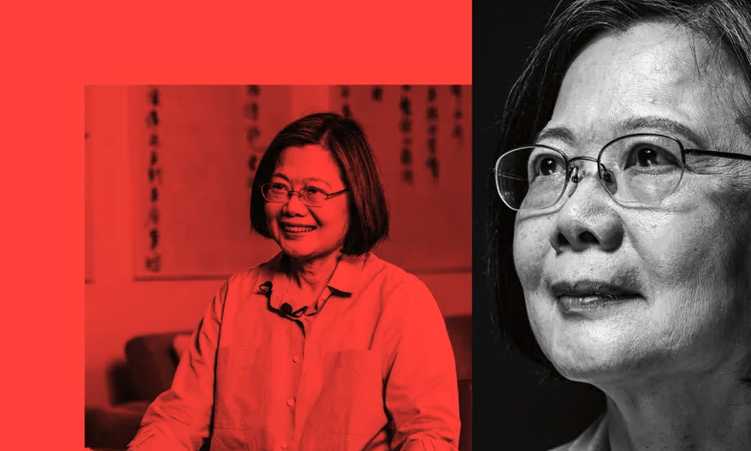

It is a well-known fact that the diminutive, soft-spoken president of Taiwan does not like doing interviews.

It’s taken months of quiet negotiations to sit down at Tsai Ing-wen’s dining table in her Taipei residence, not long before she leaves office after eight years and hands over to her successor William Lai.

Even so, the president seems keener to ask about me than talk about herself. She is certainly more comfortable showing us her cats and dogs than answering questions in front of a rolling camera.

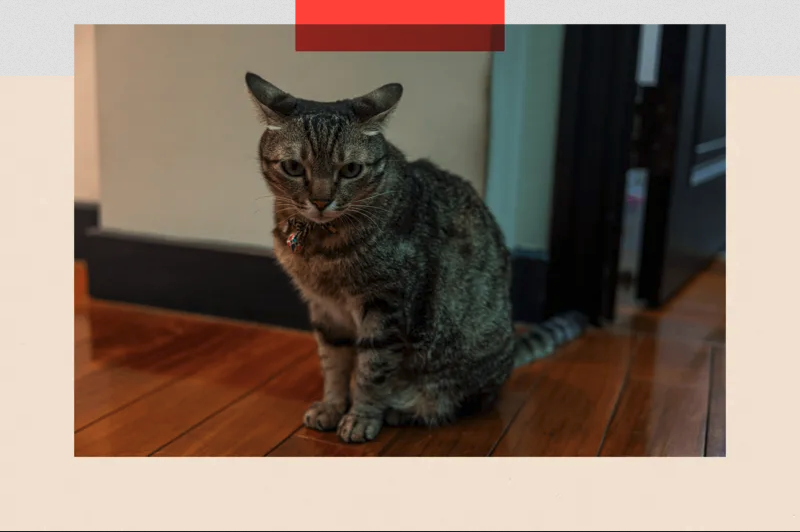

“That’s Xiang Xiang,” she says, pointing to the large, grey tabby eyeing me suspiciously through the open doorway. “Would you like to meet her?”

When Tsai Ing-wen swept to power in 2016, she was dismissed as a dull bureaucrat and ridiculed as a “cat lady” – a swipe at her for being middle-aged and unmarried. She embraced the image, appearing on magazine covers holding Xiang Xiang in her arms. Soon, her supporters adopted a new sobriquet: Taiwan’s Iron Cat Lady.

Tsai admits to a sneaking admiration for Margaret Thatcher, although she’s quick to add it’s because of her toughness as a female leader, not her social policies.

In Tsai Ing-wen, Taiwan found an unlikely champion. During her two terms, she carefully yet confidently reset the relationship with Beijing, which has claimed the independently governed island as its own for 75 years.

She stood up to an increasingly authoritarian and aggressive China under Xi Jinping; she held on to a vital US alliance under Donald Trump and buttressed it under Joe Biden. At home, she expanded the island’s defence and legalised same-sex marriage, the latter a first for Asia.

While Tsai shied away from the spotlight in Taiwan’s boisterous politics, Xiang Xiang became a celebrity. She played a starring role in Tsai’s 2020 re-election campaign, along with the president’s other cat, a ginger tom called Ah Tsai.

Tsai has her detractors. Beijing is no fan, and neither are the many older Taiwanese, who want better relations with China, where they have family and business interests. Domestically, she has been criticised for not doing enough for the economy – the rising cost of living, unaffordable housing and a lack of jobs cost her party young voters in January’s election.

And her biggest critics fear that she has made the island of 23 million more, rather than less, unsafe.

Put crudely, this is what any Taiwan leader faces: a much bigger, wealthier, and stronger neighbour, who says he owns your house, is willing to let you hand it over without a fight, but is ready to use force if you refuse. What do you do?

Tsai’s predecessor, Ma Ying-jeou, chose conciliation and a Beijing-friendly trade deal.

But he miscalculated how young Taiwanese would react to what they saw as appeasement. In 2014, thousands took to the streets in what became known as the Sunflower Movement. When President Ma refused to back down, they occupied parliament.

Two years later Tsai Ing-wen was elected on a very different calculus: that the only language Beijing understands is strength.

Now, as she prepares to step down, she says she has been vindicated: “China has become so aggressive and assertive.”

Dear Beijing – back off

“Wow, you’re really tall,” the president exclaims, craning her neck at a lanky, young soldier standing stiffly to attention.

He tells her he is 185cm and she asks, with genuine concern, “Are the beds here big enough for you?” They are, he reassures her.

This was on a recent morning in April at a new special forces training centre on the outskirts of Taipei, which Tsai had just opened.

The relaxed and chatty president disappears when she enters the cavernous dining hall, where hundreds of crew-cut recruits stand to attention and shouted “Zong Tong Hao!”, or “Hello, President!”

She almost looks out of place in these settings. Her speech is worthy and matter of fact, with no soaring rhetoric. And yet such visits are quite frequent, to make sure the military reforms she has pushed through are paying off.

One of the most difficult was a return to a year of military service for all men over the age of 18. While she admits it is not popular, she says the public accepts it is necessary: “But we have to make sure that their time spent in the military is worthwhile.”

For a former law professor and trade negotiator, Tsai has spent a surprisingly large amount of time as president donning camouflage fatigues. In one famous image she’s seen shouldering a rocket launcher. The reason: she believes Taiwan cannot hope to fend off Beijing without a modern, well-trained military in which young Taiwanese are proud to serve.

While China’s threat of invasion is not new, it is only recently that President Xi Jinping has gained the military capability to mount what would still be a huge and risky operation. His threats have also become more urgent and ominous. He has said twice that a resolution over Taiwan cannot be passed down from one generation to another, which some have interpreted to mean that he wants it done in his lifetime.

On the other side of the strait, Tsai has set about rebuilding Taiwan’s outdated, demoralised and ill-equipped ground forces. It has been an uphill struggle, but results have begun to show. Yearly defence spending has risen significantly to about $20bn (£16bn).

“Our military capability is much strengthened compared to eight years ago. The investment we have put in to military capacity is unprecedented,” Tsai says.

I have spoken to many in Taiwan’s opposition who genuinely believe Tsai’s strategy of building up the military is naive, if not dangerous. They point to China’s powerful navy, the world’s largest, and more than two million active troops. Taiwan’s forces are not even a tenth of that.

To Tsai and her supporters that is missing the point. Taiwan is not trying to defeat a Chinese invasion, they say, but dramatically increasing its price to deter China.

“The cost of taking over Taiwan is going to be enormous,” Tsai says. “What we need to do is increase the cost.”

Tsai was no stranger to Beijing, or the Chinese Communist Party, when she became president. Her unorthodox rise to power began in the mid-1990s, when she cut her teeth as a trade negotiator. She then caught the eye of Chen Shui-bian, the first president from the pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). He appointed her to run Taiwan’s top body for dealing with China. There she rewrote the book on how Taiwan should handle Beijing.

She has long known where the red lines are – and she believes that to resist China, Taiwan needs allies: “So strengthening our military capacity is one and working with our friends in the region to form a collective deterrence is another.”

Many in Tsai’s party, the DPP, now talk of a new alliance that stretches from Japan and South Korea to the north, through the Philippines to Australia in the south – with the US as quarterback, holding the team together. But this is theoretical at best. There is no Asian Nato and Taiwan enjoys no formal military alliances. Despite mutual antipathy towards Beijing, Tokyo and Manila are both deeply reluctant to vow support for Taiwan. Even that most important ally, Washington, has stopped short of guaranteeing it would put boots on the ground.

But Tsai is optimistic. “A lot of other countries in the region are alert and some of them may have a conflict with China,” she says, referring to rival claims by Beijing, Tokyo and Manila over disputed waters and islands.

“So, China is not an issue for Taiwan only. It is an issue for the whole region.”

The power of soft power

Painting China as a big, bad bully is not hard for a Taiwan president. The trickier job is to find allies who would risk irking the world’s second largest economy.

And that’s why Taiwan leads such an increasingly lonely diplomatic existence. In the last decade China has put the squeeze on many of the island’s allies who still recognise it – only 12 remain now, most of them tiny Pacific Island and Caribbean micro-states.

Tsai believes the way out of this diplomatic isolation is to build alliances with what she calls “like-minded democracies”.

To that end she hosts dozens of parliamentary delegations from all over the world, a loophole for meeting foreign dignitaries from countries that don’t see Taiwan as one. Last month I attended Holocaust Memorial Day. There was music and poetry, and an impassioned speech to never forget by the representative from Germany.

There are also more unusual events. Earlier this week, while Xi Jinping was getting ready to welcome Vladimir Putin in Beijing, Tsai Ing-wen hosted a drag performance by Taiwanese-American Nymphia Ward. “This is probably the first presidential office in the world to host a drag show,” Nymphia reportedly told Tsai.

Both are examples of brand Taiwan – a democracy that the world should care about losing.

“People say we are more important than Ukraine – strategically our position is more important and our place in the supply chain – and that they should shift support to Taiwan. We say no. The democratic countries need to support Ukraine,” Tsai says.

Rather than Taiwan’s wildly successful chip industry, which could be replicated, instead Tsai wields the one thing she has and the Chinese Communist Party doesn’t: the soft power of democracy.

In the run up to January’s election, the rainbow flag was hard to miss at every DPP rally.

“In Taiwan we are free to live how we choose. We could not do this in China,” one couple told me.

It’s a remarkable change from when I was a student here more than 30 years ago. Taiwan was still emerging from four decades of military rule. I remember a gay friend desperately looking for a way to get to America. Back then, if you were found to be homosexual during your military service you could get thrown in jail or a psychiatric ward.

That changed but Tsai Ing-wen’s government went further than any in Asia when it pushed through legislation legalising same-sex marriage in 2019. A little over half the population still opposed it. Some, including church and family groups, ran a vociferous campaign against it. It was a big political risk, and one that could have cost her re-election.

Tsai calls it a “very difficult journey” but one she saw as necessary: “It’s a test to society to see to what extent we can move forward with our values. I am actually rather proud that we managed to overcome our differences.”

Taiwan is still conservative and patriarchal. I ask Tsai if she’s worried it might return to being a “boys club” once she, the island’s first female president, steps down. “I have a lot of opinions about that boys club!” she says but does not elaborate.

The island’s strength, in her opinion, is its mixed heritage – it’s a society of immigrants.

The Chinese came in many waves, sometimes centuries apart, and they joined hundreds of thousands of indigenous peoples.

“In… [such a] society, there are a lot of challenges,” Tsai says. “People are less bound by the traditions. The main goal is to survive [as a society]. This is why we have been able to move from an authoritarian age to democracy.”

And that is why she hopes Taiwan’s most important alliance – with the world’s most powerful country and democracy – will last no matter who makes it to the White House after November.

Best friends forever?

After Donald Trump’s stunning victory in 2016, Tsai Ing-wen rang to congratulate him – and she was put through. No US President since Jimmy Carter had taken a call from the president of Taiwan. Tsai has described the call as short but intimate, and wide-ranging.

The truth is Trump is a wild card for Taiwan. He’s criticised the island for “stealing America’s semiconductor industry”, but, as Tsai points out, he has also approved more arms shipments to Taipei than any of his predecessors. But she doesn’t want to discuss him, or the possibility of his return to the Oval Office.

What she does want to emphasise is the perception of a growing China threat.

“The rest of the world is telling China that you can’t use military means [against Taiwan]. No unilateral action is allowed and no non-peaceful means is allowed and… I think China got the message,” she says.

That might be wishful thinking. There has been no noticeable decrease in military pressure. Rather, China regularly sends dozens of military aircraft and ships across the median line that divides the waters and airspace of the Taiwan strait. In 2022, Beijing declared that it no longer recognises what was effectively the border. The trigger was one of Tsai’s diplomatic coups.

US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s historic visit in 2022 was celebrated in a Taiwan starved of international recognition. But China was furious, firing ballistic missiles over the island, and into the Pacific Ocean, for the first time ever.

It was a warning. Even some inside Tsai’s own administration worried quietly that Pelosi’s visit had been a mistake.

“We’ve been isolated for such a long time,” she says. “You just can’t say no to a visit like that of Speaker Pelosi. Of course it comes with risks.”

You can feel the tension in her voice. Her opponents say the Pelosi visit was reckless and left Taiwan more exposed. Even President Biden is thought to have opposed the trip.

But Tsai says this is the line Taiwan must walk.

“I had to turn a party of revolutionaries into a party of power,” Tsai Ing-wen says of her time at the DPP’s helm.

When she took over, she was an economics graduate leading a party of older, male radicals who had spent their early lives fighting for Taiwan independence – or behind bars for it.

There is no need for Taiwan to hold a referendum or declare independence, she says, because it is already an independent, sovereign nation.

“We are on our own. We make our own decisions; we have a political system to govern this place. We have a constitution, we have laws, we have a military. We think that we are a country, and we have all the elements of a state.”

What they are waiting for, she says, is for the world to recognise it.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!