Namibia is endowed with many diversities: Cultural, ecological, geological and geographic.

And, as a resource-rich country, a variety of developmental options are available that can bring prosperity for our people.

Recently the energy and mining sectors have moved into the limelight, mainly because of oil and gas discoveries and the prospect of developing green industries – through alternative power sources such as solar, wind, hydro and biomass.

The hope is that exploiting the oil and gas reserves and alternative power sources will induce needed economic growth through industrialisation and value addition.

In addressing this, policymakers perceive the need for development being first and foremost an economic issue – how money is made and distributed across generational timespans.

However, environmental questions, especially the effects of climate change, must be considered simultaneously to ensure a safe and healthy life now and for future generations.

PROCLAMATIONS AND LEGISLATION

Unfortunately, it appears that economic and money issues are regarded as much more pressing, while environmental concerns are regarded as considerably less important.

This is especially relevant for the ‘green hydrogen, green industry’ components.

The demand for economic growth overshadows, by far, the need to act in an environmentally sustainable way.

This is substantiated by the fact that the industrial development of green hydrogen is happening in a proclaimed national park and is being funded through the Environmental Investment Fund.

This is important to note as Namibia’s national parks are proclaimed to protect and conserve biodiversity and ecological systems and processes on state land, not to develop industries.

To use them for industries, even if they’re called green, is a misuse of statutory power.

Leasing state land falls under the statutory functions of overall land administration; its demarcation is a function of the surveyor general.

Designating state land for specific use is therefore governed by laws made in parliament that grant regulatory and administrative power to several, but specific, institutions and office-bearers.

Therefore, to lease out state land for industrial development cannot be dealt with through legislation covering the administration and upkeep of national parks established to preserve and protect biodiversity and commensurate natural ecological systems and processes.

The rule of law dictates that institutions and their office-bearers can only exercise powers if they are provided for in a statute.

VITAL LIFELINE THREATENED

A similar situation is developing in the Kalahari Desert.

Mining licences may be granted for mining methods that risk permanently polluting a substantive ground water aquifer on which human lives and livelihoods depend, as well as natural life.

It entails uranium being mined with all tailings being discharged into the aquifer. Exploration is already under way.

The Stampriet Aquifer is the only reliable permanent fresh water source on which the ecosystem and a community of around 80 000 people depend.

The gain would be purely economic with an extremely narrow spread into the local community, if at all.

Environmentally, it appears that a sacrificial approach is being adopted.

This means that in areas in national parks leased out for industrial development, the ecological systems and processes and their biodiversity (that were to be protected) will be sacrificed for economic growth.

In the very old and sensitive ecosystem of the Kalahari Desert it could mean that some may be completely lost.

THE WEALTH TRAP

The mining and energy sectors are being portrayed as possible saviours of the Namibian economy and are gaining traction on the development agenda.

However, this sector’s track record is not commensurate with such hopes.

Where mining has produced immense wealth, it has not spread to local communities, but rather to multinational entities elsewhere.

The energy sector has neither the ability to satisfy all Namibia’s power demands, providing only about 60% of the power, nor energy needs with 0% of oil- and gas-based energy needs being provided from Namibian sources.

If the goal is power and energy self-sufficiency (which it should be) both subsectors fall drastically short.

They must therefore be fundamentally realigned to serve Namibia’s economic needs, rather than those of exclusively foreign investor needs.

ACCOUNTABILITY

Economic growth in the real economy is desperately needed for wealth creation within the Namibian economy and a less skew, more equal, wealth distribution. GDP growth alone, without any quality, is unsustainable.

Environmentally sustainable utilisation of resources – without destroying ecological systems, especially fragile and unique ones such as in the Southern Namibia Desert – must trump economically driven priorities, which are not environmentally sustainable or which don’t create meaningful wealth in Namibian communities.

The Constitution sets this out as general policy and it must percolate into the development agenda.

The utilisation of natural resources, both renewable and non-renewable, must be regulated and implemented in a transparent and accountable manner.

Benefits derived from the right to access such resources must be done so that they are shared in a way that has meaning within the Namibian economy; wealth must also be created within the Namibian population.

These principles should be set firmly in binding legislation for all investors regardless of whether they are domestic or foreign.

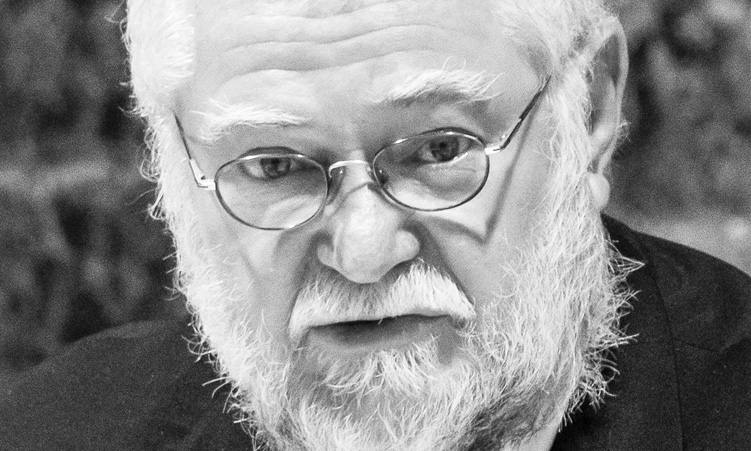

- • Calle Schlettwein is the Minister of Agriculture, Water and Land Reform

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!