The Government of National Unity’s power-sharing model will be the foundation going forward – a new centre will form, says DA federal chairperson Helen Zille. This means the Government of National Unity is not going anywhere; it might just have a different political party mix.

DA federal chairperson Helen Zille says it is improbable that any party in South Africa will get a majority vote again, showing that the idea of a Government of National Unity (GNU) is here to stay.

This week marks 100 days since the GNU was formed. It has survived, and been well received locally and globally, but only sometimes in the ANC, which is the lead partner, with the DA as a second lead.

“In time, the ANC will disintegrate,” says Zille “and, in its place, a new political centre will form.”

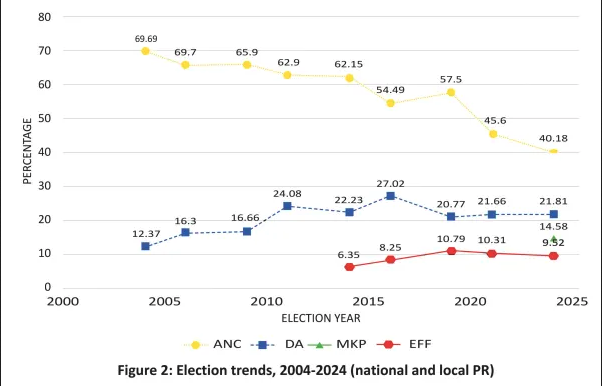

Zille said: “No party [is likely to] get above 50% [in an election] again. It’s possible, but unlikely.”

When Zille was asked if the same was true for the DA, she said: “We don’t have a ceiling.”

However, in the May election, the DA did not reach its ambitious goal of getting more than 30%, plateauing at 21.8%. Zille says that, in an era of coalition governments, anything over 20% support is significant.

The ANC’s strategy is to use the GNU to rebuild its image with disillusioned voters and claw back the majority it has lost for the first time in 30 years.

Zille says: “There will be a realignment of the centre and a new majority of constitutionalists [will be formed].”

At the height of the State Capture era, when reformists in the ANC struggled to gain dominance, every day there was talk of a new centre as veteran supporters assessed the depth of support for the dominant Radical Economic Transformation figures who ran the ANC with Jacob Zuma.

That faction has left to join the MK party, which at 14.6% had the best showing by a start-up splinter party since 1994.

In 2017, President Cyril Ramaphosa won the party presidency. In his words, it was only a “beachhead” of support for reforming the ANC. He has just over 1,000 days left in office before he becomes a lame-duck President when he steps down from the party’s top job at the end of 2027.

Pushback against the GNU within the ANC and in its tripartite alliance is significant. This week’s one-day strike by Cosatu was a proxy strike against the GNU, and the South African Communist Party is tepid about power sharing and sceptical of the role of capital in keeping it on track.

The fact that the business community approves of the GNU in a spirit of market acclaim reveals the shadow on its left.

Deputy President Paul Mashatile is regarded as the ANC heir incumbent, and his power base is Gauteng, where provincial party leaders have resisted the GNU spirit. Gauteng Premier Panyaza Lesufi torpedoed provincial power sharing and, this week, the ANC in the province allied with ActionSA to form a metropolitan government in Tshwane. It overrode its principle that, as the biggest party, it should take the mayor’s chain and has agreed for ActionSA’s Dr Nasiphi Moya to take the top seat.

For the DA, this move may hurt in the short term but, in the medium term, it plays into its plans to sustain its gains in the cities and ride on a sharp service decline in the three Gauteng metros to consolidate a base in the north of the country.

The outcome of the next ANC conference, says Zille, will begin repositioning a new political centre for South Africa. For a party to grow, she says, it needs three things. “It must have a coherent political philosophy, strong internal institutions from branches upwards and it must crowd in talent.”

The implication is that the largest party no longer has these attributes, but it still has a liberation ethos that continues to resonate with South Africans. In his assessment of the election, ANC grandee and National Executive Committee member Joel Netshitenzhe says: “The liberation ideal has not been defeated in the 2024 elections. It is alive and well, dispersed across many platforms, and in some instances hijacked by pretentious rhetoric.”

He casts his analysis wide to find that parties with roots in the liberation Struggle had a collective support of 66%.

“Parties that have their origins in the politics of the liberation movement [including as splinters] are, in the main: ANC, PAC/APC, Azapo, UDM, Cope, EFF, ATM and MK. The aggregate support for this grouping was 63.8% in 1994, 70.4% in 2019 and now at 66%.

“This therefore suggests that the liberation idea still lives – the mass forces that seek the elimination of apartheid colonial relations remain committed to this ideal. However, a significant bloc among them – including millions who abstained – has lost confidence in the ANC as the pre-eminent platform to attain this objective,” wrote Netshitenzhe.

He has charted how the ANC’s decline is mirrored in election after election, with local government elections leading to shape-shifting declines for Africa’s oldest liberation movement.

The assessment says that parties with a history in “white politics” garnered 28.82% of the vote.

A sizeable lobby in the ANC wanted to form a GNU from the liberation movement parties, but negotiators chose a power-sharing model built from both sides, including the Patriotic Alliance (PA). The PA started as a party rooted in coloured communities but is growing fast enough to have a broader appeal.

Depending on who wins the ANC presidency in December 2027, South Africa’s political landscape will realign either by consolidating the social democratic centre of the GNU now in place or a more populist and left centre. In this context, a centre refers to one that holds the polity together rather than centrist conservatism.

“The GNU will have to hew its way to higher rates of growth and development in complex domestic and global milieus. What is clear, though, is that socioeconomic policy will need serious focus on the vulnerable [mainly unskilled and semiskilled workers, and women and youth].

“The multiparty government should consciously avoid a political centre’s macabre dance of death: a cold elite rationality which is desensitised to mass aspirations and sentiment, and thus vulnerable to populist denigration,” says Netshitenzhe.

Either way, South Africa is headed into an era where the power-sharing model of the GNU will be the foundation of how governments are formed.

The first 100 days have confounded critics who expected the 10-party bloc to disassemble, given the wide range of politics and personalities at its heart. But it has sustained itself, and won the imagination both of the country and the continent for the speed with which the government was formed.

Internal competition in the Cabinet means that the public is more focused than ever before. With the next elections less than two years away, for the first time the people are finally a factor in how politics shapes South Africa.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!