To be African is not a choice, it is a condition. It is simply the only opening I have for making use of all my senses and capabilities. – Breytenbach*

He who has no memory of past struggles, the lost ones as well as those won, will have no future. – Daniël Bensaïd

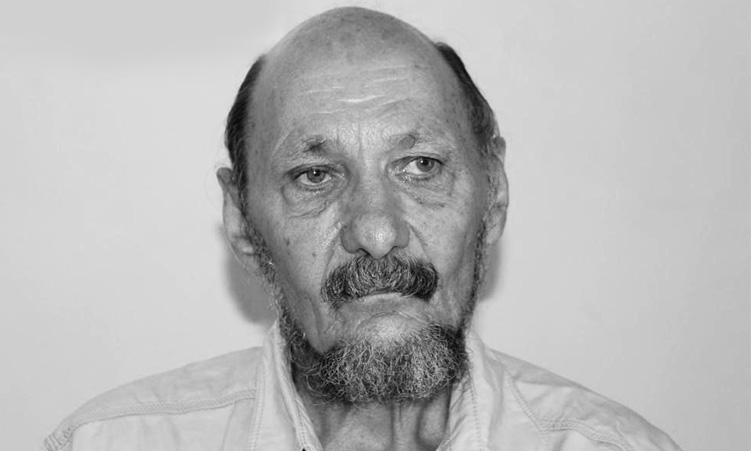

THE DEATH OF Breyten Breytenbach, South African poet, prose writer, painter and activist in Paris, France, on 24 November, leaves a deep void in the cultural and intellectual life of Africa.

Born in Bonnievale in the Western Cape on 16 September 1939, Breyten came from a creative family of authors, photo-journalists and military officers.

While he left South Africa for Paris in the early 1960s, where he married a Vietnamese women, Yolande, Mariposa Sonrisa Ruiseñor, his heart’s partner, he remained quintessentially African.

Apartheid meant that after his marriage he was not allowed to return to the country of his birth for many years.

INCARCERATION

Much later, he co-founded Okhela [Zulu: ignite the flame], a resistance group fighting apartheid in exile.

On an illegal visit to South Africa in 1975, Breytenbach was betrayed, arrested and sentenced to nine years of imprisonment for high treason.

The author recounted his experiences in a richly-textured book, ‘The True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist’, in 1984.

Released in 1982 as a result of international and domestic pressure, he returned to Paris and lived alternatively in Paris and Gorée Island, Senegal, where he founded and headed a fine art workshop for African artists.

This was the beginning of a long and deep engagement with West Africa that profoundly shaped his eventful life.

WRITER, ARTIST, PUBLIC INTELLECTUAL

As a prodigiously productive writer and thinker, his work includes several anthologies of poetry, novels and essays, many of which are in Afrikaans, many translated from Afrikaans to English, and many published originally in English. His first public engagement in the literary field, titled ‘Die Swart Kaart’ (in which he outlined his philosophy of art and literature against the literary currents at the time) appeared in the November 1964 edition of the literary magazine Sestiger.

Initially his work resonated with the literary and art currents of the time: Symbolism, Surrealism, the New Realists and the Sestigers, an Afrikaans literary movement that included writers such as Bartho Smit, Etienne Leroux and André P Brink, among others.

He was undoubtedly an influential writer and critical thinker in the literary, political and philosophical realms.

Some of his most memorable collected speeches were published by Penguin Books (2015) under the title ‘Parool/Parole’.

This collection provides a unique insight into the mind and heart of a dialectical thinker as it amounts to a topography of critical engagement with ethics and the emphatic imagination in politics and life.

LITERARY WORK

Before saying something about his literary work, allow the writer to speak for himself on how he saw his role in society.

This direct quotation comes from his memorable speech at the Skrywersberaad/Writers’ Summit of July 1989. It reads verbatim:

“As a writer I shall continue attempting to plot the shifts in power and conceptions; to help keep alive the dream of a free, democratic, decent and just South Africa; to help foster notions of the ethics of resistance; of the need to build democracy, to elicit dialogue, to test ideas, to promote resilience, to nurture revolutionary patience, to ask for respect for the texture of consciousness, to shore up international solidarity, to shore up fire …

“Our contribution is our rich diversity, our recognition of the need to go beyond ourselves, to enlarge, embrace, draw forward, maybe even to blend extremes while keeping the common good in mind.”

On one level, Breytenbach’s work is best described as an artist’s enduring and playful search for his own identity.

This was mediated by his biography as an exile, political activist, polymath cosmopolitan and traveller between worlds and cultures.

On another level, Breytenbach engaged with the complexities of the lived experience, the fragile consciousness of the power and limits of words, concepts and language and the tyranny of modernity.

This, in turn, relates to the relationship between language – especially Afrikaans – and public power and how meanings are created and debunked.

Afrikaans was both part of justifying racism and apartheid, as well as one of the means for bursting the petrified arteries of the Afrikaner elite.

COUNTER-HEGEMONIC THINKER

The above made Breytenbach a counter-hegemonic thinker, deeply suspicious of all constructs of power and their vulgarities.

In this he was influenced by the French intellectual and writer, Albert Camus, and by a brand of Zen Buddhism.

Camus had a nose for those oppositions which possess a genuinely emancipatory potential from which he could wrest meaning.

Breyten’s essay, ‘Imagine Africa’, originally presented at the ArtTerial conference, Gorée Island, in March 2007, provides one of the most nuanced articulations of envisioning Africa and its future differently.

His conclusion is particularly poignant for the present and the future.

It reads: “For I believe that it is possible to strengthen and season the freedom of the mind, singly and collectively and that this freedom constitutes the necessary lever for bringing about further changes.”

Such were his artistic gifts, that he refused to accept and endure the alienating emptiness of apartheid.

Instead, he invoked the power of a composite identity: Afrikaner/African.

Two sources are especially useful in understanding this construct: The author’s ‘The Afrikaner as African’, a paper he read at a conference in Zanzibar in May 1998, and his insightful preface to Frederik van Zyl Slabbert’s ‘Afrikaner Afrikaan Anekdotes en Analise’; (Afrikaner African Anecdotes and Analysis) published in 1999.

Of course, Breytenbach was not alone in this. Frederik Van Zyl Slabbert, André P Brink, C Louis Leipoldt, Bram Fischer, Uys Krige, Antjie Krog, Martin Versfeld, Johan Degenaar, Neville Alexander, Etienne Leroux, Beyers Naude and others, departed from the premise that the ethical life vests in engagement; that they were part of Africa, and that reconciliation was ultimately a cultural and not a political project.

THE BEAUTY OF NATURE

Yet another theme enriches his work: His deep engagement with nature.

The author found redemptive meaning in the natural splendours of South Africa and Africa.

Unlike so many intellectuals, he would never renounce the need for beauty. ‘Return to Paradise’ (1993) is Breytenbach’s latest exploration of his African and South African identity: A journey of the heart and mind into his complex relationship with the country of his birth.

In it he writes of the beauty of the mountains, valleys, rivers, vineyards, orchards, heat, wind, mostly of the Boland, where he grew up and went to school.

MIDDLE WORLD

Breytenbach’s ‘Notes from the Middle World’, his Fernando Pesson lecture (eThekwini, 7 October 1996) explores the question of identity: ‘Who are You?’ with commendable insight.

He traces the origin of the Middle World to Constantine Cavafy, the Alexandrian poet of Greek extraction who died in 1933.

He it was who famously wrote: “And now, what’s going to happen to us without barbarians? They were, those people, a kind of solution.”

His poetry, as well as his prose, have been marked by a combination of Kafkaesque and a dose of Buddhist scepticism and a celebration of life; images connect often surreal worlds to the grinding realities of apartheid, magical realism to critical realism.

His was not the easy ideological answer, but the search for what makes us truly human and free.

On a personal note, I met Breyten Breytenbach through his work in 1967 and at Dakar, Senegal, in July 1987 as part of a delegation of South African passport holders who journeyed to West Africa to engage in discussions with the African National Congress (ANC) on the future of South Africa.

Breyten and his beloved wife, Yolande, visited Namibia in February 2017.

On that occasion, he spoke about The Middle World and how to reimagine Africa at a meeting of the local Socratic Society.

The vision has not faded in his pilgrimage of 85 years, nor is it likely to fade soon.

Thank you, Breyten for your radical freedom and infectious humanity and for inventing and mining words in all their frailty and power.

May the Force be with Yolande, the children, family and friends.

* André du Pisani is emeritus professor of politics at the University of Namibia

- * Breyten Breytenbach, ‘Return to Paradise’.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!