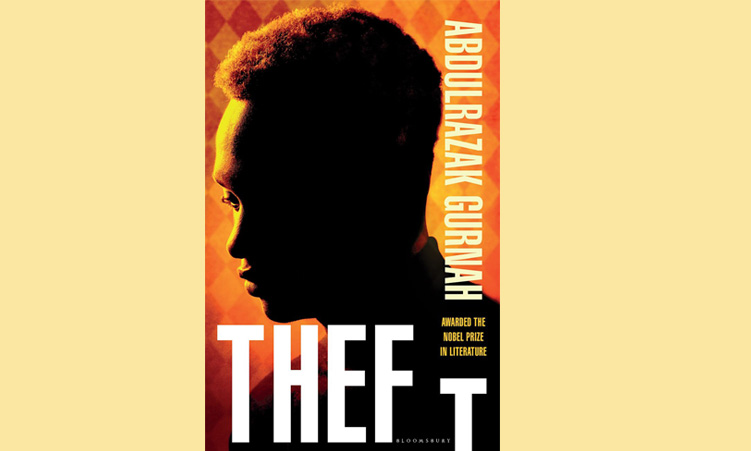

The receipt of a big award inevitably ramps up the pressure on whatever the winner publishes next, but there can be no such fears over Abdulrazak Gurnah’s, ‘Theft’, his first since becoming a Nobel laureate in 2021.

Set between his birthplace, Zanzibar, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, it’s a quietly powerful demonstration of storytelling mastery, at once coming-of-age chamber piece and wide-angled postcolonial panorama, pegged to the inner lives of its central trio – all teenagers followed into adulthood.

Meanwhile, sketched between the lines, is family heartache spread over several generations, all narrated in a quicksilver style that gives you the pleasurable sense that you’re putty in the hands of a warm yet clear-eyed authorial intelligence.

It begins by tracing the marital misery that led to one of its characters, Karim, growing up under the eye of a stepbrother who nurtures his ambition to go to university.

His story is twined with the unexplained arrival of a younger boy, Badar, an orphan seemingly taken into servitude in Karim’s well-off household; a murky arrangement considered payback for an ancestral wrong alluded to in the book’s title, and a state of affairs that unsurprisingly lights a slow-burn fuse of envy, suspicion and resentment.

We see the boys as teenagers, then adults, as the novel moves from the 90s into the 00s, with nothing directly stated about the timeline, unless you count a passing mention of radio headlines about Srebrenica and Yitzhak Rabin.

Karim and Badar’s separate experience of parental abandonment leaves them with a certain fellow feeling in spite of their divergent circumstances in the here and now, and the narrative is shaped around their uneasy co-dependency against the backdrop of Zanzibar’s post-independence transition from proxy cold war battleground to service-economy playground for wealthy foreigners whose whims have the power to brutally upend the lives of its inhabitants, as the novel’s left-turn climax shows.

The story, rife with pathos, is told from both boys’ points of view, as well as that of Fauzia, a schoolgirl whose epilepsy leaves her parents fretting about her marriage hopes. Badar and Karim’s separate inheritance of loss will take its toll on her life too, as the book’s initially unhurried pace ratchets up into nigh-on unbearable tension.

Throughout, Gurnah nimbly covers vast acres of storyline: witness the five-page stretch when Karim becomes a new dad, sweeping us from gleeful pregnancy announcement to toxic household squabbles, not entirely assuaged by uncle Badar’s newfound ability to settle a crying child.

Sometimes the characters know more than we do, sometimes less, and Gurnah’s consistently wrongfooting approach supplies a large part of the book’s energy.

It all keeps us on our toes, as does Gurnah’s habit of revealing pivotal events almost as if inadvertently letting them slip; an appealing narrative delivery mechanism, as though he’s casually sprinkling the action with dozens of little plot twists.

The technique not only grips our attention but adds to a sense of characters buffeted by historical forces beyond their control, a predicament that the book discreetly allows to let hang in the air as a symptom of post-imperial aftershock.

The conclusion – crackling with jeopardy, ultimately cathartic – moves all of the patiently assembled plotlines of ‘Theft’ into place for a riveting denouement that is both unguessable yet entirely in keeping with the logic of a book whose emotional heft derives from situating us inside a particular character’s understanding, only to shatter it with a switch to another point of view.

In dramatising the difficulty of escaping the shadow of a past its protagonists can’t understand, Gurnah flirts with crushingly gloomy determinism as well as the sunnier possibilities of hope, and it’s not the least of this wonderful title’s achievements that it leaves you wondering to the very last which way he’s going to go.

– The Guardian

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!