Farai Makamba, a 27-year-old student from Zimbabwe, used to keep his university books on his desk at home in Beirut.

Now they’ve been replaced by his passport, travel documents, and cash.

“I have a plan for myself in case I need to leave urgently,” he says.

Mr Makamba, whose name we have changed to protect his identity, returned to Lebanon in September to finish the final year of his master’s degree in mechanical engineering.

He spent the summer holiday at home in Harare.

He came back with the hope that the conflict would de-escalate. But since Hamas attacked Israel on 7 October last year, there has been near-daily cross-border fire between Israel and Hamas’s ally Hezbollah, the Iran-backed military group which is based in Lebanon.

This last week has seen the deadliest days of conflict in Lebanon in almost 20 years.

As many as one million people have been forced from their homes across Lebanon, the country’s Prime Minister, Najib Mikati, has said.

Israel’s military says it is carrying out a wave of “extensive” strikes in southern Lebanon and the Beqaa area, aiming to destroy Hezbollah infrastructure. The group’s leader Hassan Nasrallah was killed in an airstrike on Friday.

The week before last, 39 people were killed and thousands wounded when pagers and walkie-talkies used by Hezbollah members exploded across the country. Hezbollah blamed Israel, which has neither confirmed nor denied it was behind the attack.

The US, UK, Australia, France, Canada and India have all issued official advice for their citizens to leave Lebanon as soon as possible.

African students have told BBC News they now face a dilemma – whether to remain in Lebanon as Israel continues to attack or return home to countries such as Uganda, Zimbabwe and Cameroon.

At the American University of Beirut (AUB), where Mr Makamba is studying, there are around 90 African students on a scholarship programme.

Mr Makamba says there has been a “huge jump in fear” among students, especially since the pager and walkie-talkie explosions.

“We don’t know who is carrying a ticking time bomb in their pockets,” he says.

“Is it your taxi driver? Is it your Uber driver? Is it the person you are walking next to?”

Mr Makamba’s days used to be filled with classes and seeing friends. Now he says he only leaves the house to go to shop for essentials and the tension is palpable.

He recently stocked up on staples such as bread, pasta and bottled water in case of shortages.

The campus is closed and several of his classes have been moved online.

“Everyone is nervous. Even the way we communicate is different,” he says.

“When we finish class, our professor now says: ‘Have a good day and stay safe.’ We say the same thing because we know what is happening in the country.”

“No-one is safe.”

Public schools have also closed and the ministry of education says they are being used to accommodate people who have fled their homes because of the Israeli airstrikes in the south of the country.

The scholarship programme funding African students at AUB has given international students the option to go home and finish their course online.

But some say that will not be possible.

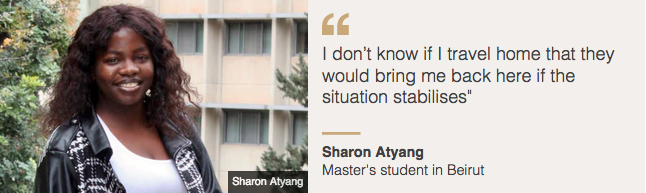

Sharon Atyang, a 27-year-old student from northern Uganda, is currently completing her master’s in community development at AUB.

She says electricity and internet issues at home will make it almost impossible to complete her studies online.

“I am also on a scholarship, and I don’t know if I travel home that they would bring me back here if the situation stabilises,” she says.

Adele Pascaline from Cameroon, whose name has been changed to protect her identity, also says completing her undergraduate radiology degree back home will be almost impossible.

“I cannot do my clinical rotations back home, but I need to complete them as part of my degree,” she says.

Nevertheless, the continuing attacks have meant she now has a return ticket.

The Mastercard Scholarship Program finances dozens of African students in Lebanon.

Mastercard Foundation said it is closely monitoring developments and working with AUB to support students.

Its spokesperson said: “AUB is regularly communicating with the students and has offered support for their health and well-being.

“The academic curriculum remains flexible and necessary accommodations have been made to account for the current disruptions and to ensure academic continuity for the enrolled students. International students who wish to return home are supported to do so.”

While it is still possible to leave Beirut via the international airport, tickets are difficult to get hold of. Several airlines such as Emirates, Qatar Airways, Air France and Lufthansa have suspended their flights to and from the city.

Ms Atyang says that from her bedroom in Beirut, she can hear the sounds of the sonic booms caused by Israeli fighter jets flying low over the city.

“I was in a reading room and when I heard the sound barrier breaking, I just ran. But I had nowhere to run. I found myself hiding in the toilet,” she says.

The stress of waiting for another attack has left her “emotionally and mentally unstable – [unable] to do anything”.

She said many students have asked their professors to extend deadlines for assignments.

Between trying to study and write her thesis, Sharon is also answering frantic calls from her family in Uganda.

“They are demanding that I go back home, they are telling me I need to prioritise my life over academics.”

Some African governments have begun evacuations.

The Principal Secretary for Diaspora Affairs in Kenya, Roseline Njogu, confirmed that nine Kenyans had arrived back in the country in August.

She urged other Kenyans who wished to leave to register for evacuation with the embassy. There are an estimated 26,000 Kenyans currently in Lebanon.

Last month, the former spokesperson for Ethiopia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Nebiyu Tedla, told the BBC they were monitoring the situation closely and were “preparing plans to evacuate if necessary”.

He added that there are an estimated 150,000 Ethiopians in Lebanon, the vast majority domestic workers.

Some of these workers face additional challenges as they work under Lebanon’s strict kafala system, which means they must ask permission from their employers to leave.

For students like Mr Makamba and Ms Atyang, getting out of Lebanon might be easier to organise. But they are held back because of their desperation to finish their studies.

Both say they will make a decision in the next few days.

Ms Atyang says it is particularly hard for African students.

“You are on your own, and you have to take care of yourself,” she says.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!