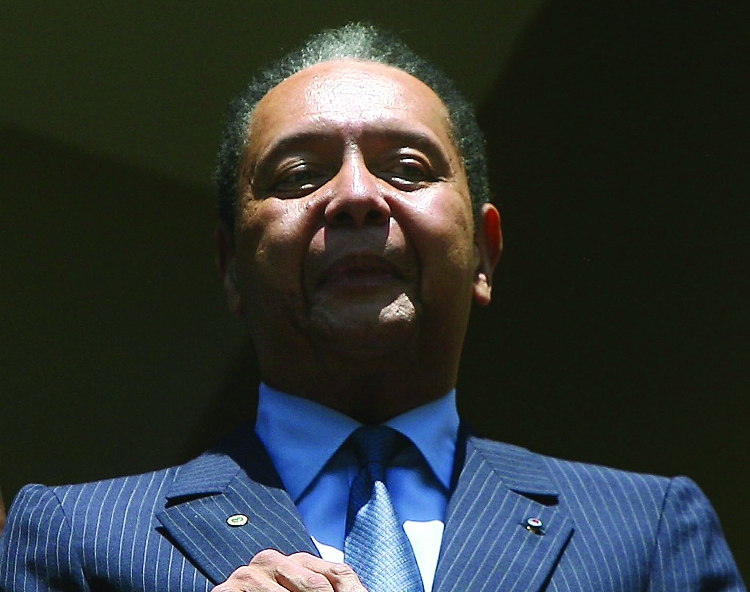

•Clarens RENOISHaiti’s former dictator Jean-Claude ‘Baby Doc’ Duvalier, who ruled the impoverished Caribbean nation with an iron fist from 1971 until his ouster in 1986, died on Saturday of a heart attack. He was 63.

The death of Baby Doc, as he was commonly known, marks the end of a dark chapter for a desperate country plundered first by his ruthless father – Francois ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier, a physician-turned-populist politician – before being further ravaged by his son.

An estimated 30 000 people were killed during the reign of the Duvalier father and son, rights activists say.

Baby Doc returned to Haiti in 2011, after 25 years of exile, but victims, opponents and activists never saw him face justice.

Despite that, reaction to his death was muted on the streets of Haiti.

President Michel Martelly, on Twitter, called him “an authentic son of Haiti” and sent his “sincere condolences to the family and to the nation”.

“Love and reconciliation must always prevail over our internal quarrels. May he rest in peace,” wrote Martelly, who said he was paying tribute to the former president “despite our quarrels and our differences”.

Baby Doc’s death in the capital Port-au-Prince was announced by the health minister, Florence Guillaume Duperval, who said the cause appeared to be a massive heart attack.

The younger Duvalier came to power when he was just 19 years old, and for a decade-and-a-half ruled as Haiti’s self-proclaimed ‘president for life’.

Like his father, Baby Doc allowed little room for dissent, barring opposition, clamping down on dissidents, rubber-stamping his own laws and pocketing government revenue.

And like his father, he made liberal use of the dreaded Tonton Macoutes, a secret police force loyal to the Duvalier family.

The notorious sunglass-wearing Macoutes terrorised Haitians, arresting and torturing untold numbers of political opponents, thousands of whom vanished without ever being accounted for.

Born in Port-au-Prince on 3 July 1951, the young Duvalier watched the intrigue and paranoia escalate in his father’s 14-year government, which began in 1957 and saw waves of arrests, executions, bombings and 11 failed coups.

At the age of 11, he survived an attack that killed three of his bodyguards.

In 1986, he was forced into exile in a popular uprising, as pro-democracy forces rallied in the streets amid international condemnation of the rampant human rights abuses during his regime.

Baby Doc fled Haiti for a life of luxury in France, thanks to the hundreds of millions of dollars allegedly pilfered from the coffers of the most impoverished country in the Americas.

He was said in reports to have looted as much as US$300 million before being forced to flee.

In the late 1990s, former political prisoners brought charges of “crimes against humanity” against Baby Doc in a Paris court, claiming they were tortured over a period of years, but the lawsuit later foundered.

In 2007, Duvalier called on Haitians to forgive him for “mistakes” committed during his rule, even as the government in power at the time insisted he face trial.

After his return, he was charged in a slow-moving prosecution on corruption and embezzlement allegations dating to his years in power.

Efforts to bring him to justice became tangled in legal motions and appeals, and proved unsuccessful in the end.

Reed Brody of Human Rights Watch, who helped victims build their criminal case against Duvalier, lamented that the former dictator never paid for his crimes.

“Duvalier’s rule was marked by systematic human rights violations. Hundreds of political prisoners held in a network of prisons died from mistreatment or were victims of extrajudicial killings,” Brody said.

“Duvalier’s government repeatedly closed independent newspapers and radio stations. Journalists were beaten, in some cases tortured, jailed, and forced to leave the country.”

Baby Doc returned to Haiti on 16 January 2011 in what he said was a gesture of solidarity with a nation that had been devastated the year before by a massive earthquake, which levelled much of Port-au-Prince and claimed more than 100 000 lives.

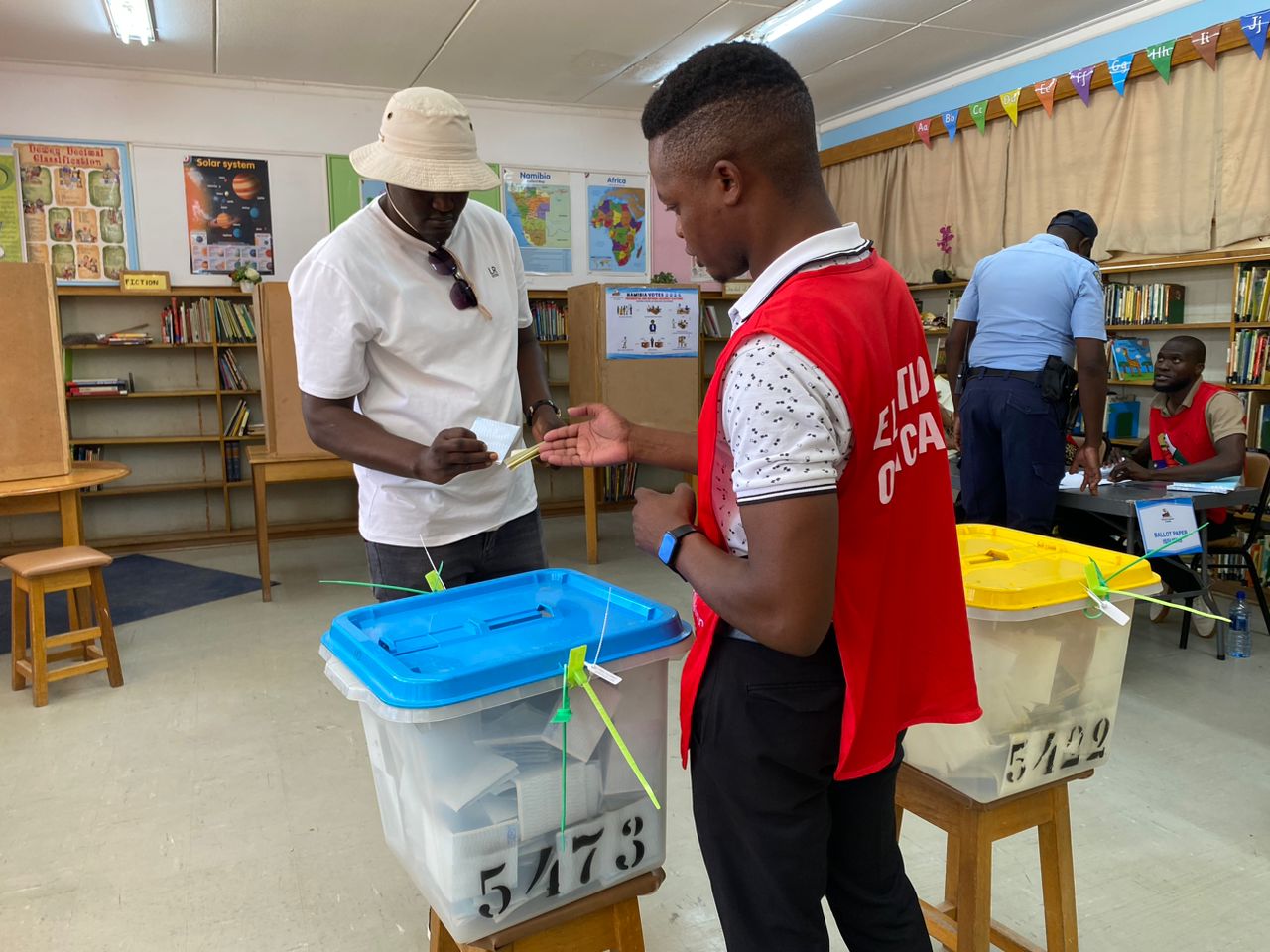

The day after his unexpected return, police arrested him on charges of embezzlement. In February 2013, he pleaded not guilty to charges of corruption and human rights abuses.

Other than his brief jailing shortly after his arrival, he remained free for the rest of his life.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!