Veteran French conservative Michel Barnier has taken over as prime minister, almost two months after France’s snap elections ended in political stalemate.

He said France had come to a “serious moment” and he was facing it with humility: “All political forces will have to be respected and listened to, and I mean all.”

President Emmanuel Macron named the EU’s former chief Brexit negotiator, ending weeks of talks with political parties and potential candidates.

Mr Barnier, 73, arrived at the prime minister’s residence at Hôtel Matignon in Paris on Thursday evening, taking over the role from Gabriel Attal, France’s youngest ever prime minister who has been in office for the past eight months.

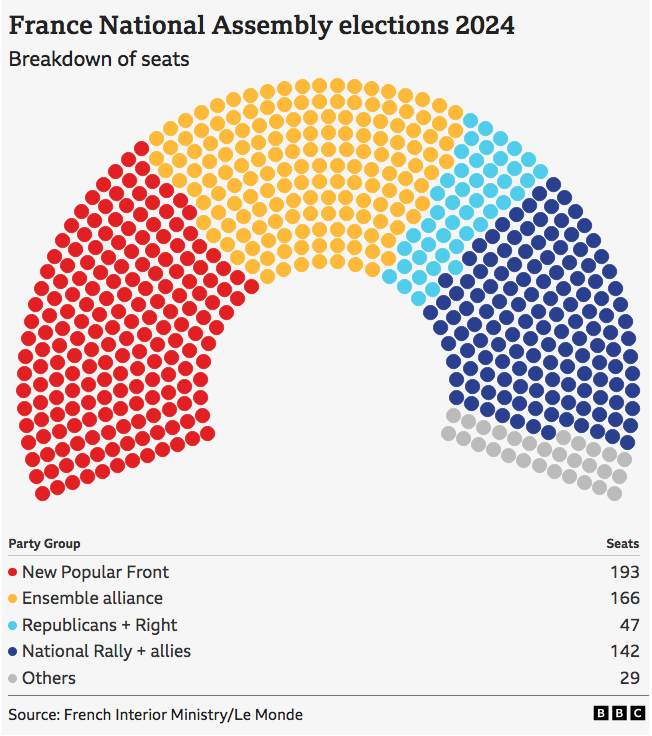

His immediate task will be to form a government that can survive a National Assembly divided into three big political blocs, with none able to form a clear majority.

But Mr Barnier will need all his political skills to navigate the coming weeks, with the centre-left Socialists already planning to challenge his appointment with a vote of confidence.

He said he would respond in the coming days to the “challenges, the anger and the sense of being abandoned and of injustice that run through our towns and countryside”.

He promised to tell the truth to the French people about the financial and environmental challenges facing the country, and to work with “all those in good faith” towards great respect and unity.

It has taken President Macron 60 days to make up his mind on choosing a prime minister, having called a “political truce” during the Paris Olympics.

In his farewell speech outside Hôtel Matignon, Gabriel Attal said “French politics is sick, but a cure is possible, provided that we all agree to move away from sectarianism”.

Having led the marathon talks on the UK’s exit from the European Union between 2016 and 2019, Mr Barnier has considerable experience of political deadlock. He has had a long political career in France as well as the EU and has long been part of the right-wing Republicans (LR) party.

Known in France as Monsieur Brexit, he is France’s oldest prime minister since the Fifth Republic came into being in 1958.

Three years ago, he tried and failed to become his party’s candidate to take on President Macron for the French presidency. He said he wanted to limit and take control of immigration.

Mr Macron’s presidency lasts until 2027. Normally the government comes from the president’s party, as they are elected weeks apart.

But the man who has called himself “the master of the clocks” changed that when he called snap elections in June and his centrists came second to the left-wing New Popular Front.

President Macron has interviewed several potential candidates for the role of prime minister, but his task was complicated by the need to come up with a name who could survive a so-called censure vote on their first appearance in the National Assembly.

The Elysée Palace said that by appointing Mr Barnier, the president had ensured that the prime minister and future government would offer the greatest possible stability and the broadest possible unity.

Mr Barnier had been given the task of forming a unifying government “in the service of the country and the French people”, the presidency stressed.

Mr Barnier’s initial challenge as prime minister will be to steer through France’s 2025 budget and he has until 1 October to submit a draft plan to the National Assembly.

Gabriel Attal has already been working on a provisional budget over the summer, but getting it past MPs will require all Mr Barnier’s political skills.

His nomination has already caused discontent within the New Popular Front (NFP), whose own candidate for prime minister was rejected by the president.

Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the leader of the radical France Unbowed (LFI) – the biggest of the four parties that make up the NFP – said the election had been “stolen from the French people”.

Instead of coming from the the alliance that came first on 7 July, he complained that the prime minister would be “a member of a party that came last”, referring to the Republicans.

“This is now essentially a Macron-Le Pen government,” said Mr Mélenchon, referring to the leader of the far-right National Rally (RN).

He then called for people to join a left-wing protest against Mr Macron’s decision planned for Saturday.

To survive a vote of confidence, Mr Barnier will need to persuade 289 MPs in the 577-seat National Assembly to back his government.

Marine Le Pen has made clear her party will not take part in his administration, but she said he at least appeared to meet National Rally’s initial requirement, as someone who “respected different political forces”.

Jordan Bardella, the 28-year-old president of the RN, said Mr Barnier would be judged on his words, his actions and his decisions on France’s next budget, which has to be put before parliament by 1 October.

He cited the cost of living, security and immigration as major emergencies for the French people, adding that “we hold all means of political action in reserve if this is not the case in the coming weeks”.

Mr Barnier is likely to attract support from the president’s centrist Ensemble alliance. Macron ally Yaël Braun-Pivet, who is president of the National Assembly, congratulated the nominee and said MPs would now have to play their full part: “Our mandate obliges us to.”

The former Brexit negotiator had only emerged as a potential candidate late on Wednesday afternoon.

Until then, two other experienced politicians had been touted as most likely candidates: former Socialist prime minister Bernard Cazeneuve and Republicans regional leader Xavier Bertrand. But it soon became apparent that neither would have survived a vote of confidence.

That was Mr Macron’s explanation for turning down the left-wing candidate, Lucie Castets, a senior civil servant in Paris who he said would have fallen at the first hurdle.

The president has been widely criticised for igniting France’s political crisis.

A recent opinion poll suggested that 51% of French voters thought the president should resign.

There is little chance of that, but the man Mr Macron picked as his first prime minister in 2017, Édouard Philippe, has now put his name forward three years early for the next presidential election.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!