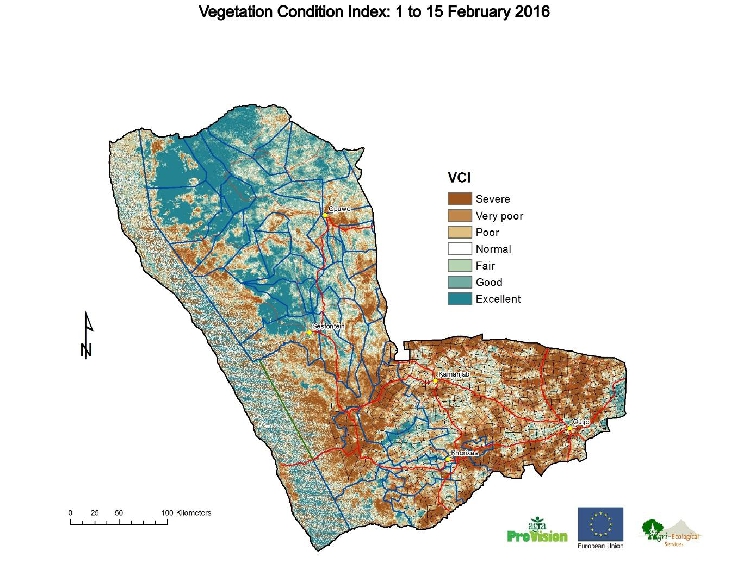

TWO types of drought are pestering Namibia this year: climatic and man-made. The climatic drought is caused by too little rain. On the map of the Kunene region, the brown areas around Outjo, Kamanjab, Khorixas and south of Sesfontein received too little rain. The vegetation is dry, even though it is already late February, normally the height of the rainy season.

On the other hand, the northern Kunene region is blue. It has received a lot of rain. Its vegetation is green. Yet, we all know that farmers in the northern Kunene also suffer drought, despite the copious rain. Only the mopane/omusati is green; there is no grass. Grazing cattle destroyed the grass sward long ago and now, all the rain in the world will not make it grow again. The green mopane reflects the good rainfall. The hungry people reflect the broken grass sward, destroyed by injudicious grazing. The northern Kunene suffers a man-made drought. And because we caused it, we can do something about it, too.

The grass sward is broken by too many livestock (especially grass-eating cattle) being present on the land, always. I don’t think there are necessarily too many cattle on the land in the Kunene. Regular droughts like the present one cause large numbers of cattle to die off and bring the population size down again to its ecological limits.

The poor grass sward is caused more by the cattle being always there. What little grass starts growing in response to rainfall is grazed down immediately by cattle. Everywhere. Throughout the whole rainy season. Grass does not get a chance to grow out, establish itself and reproduce. It is eaten to death. Rain or no rain, there is no grass.

How to cope with this man-made drought? Various Namibian Acts of Parliament empower local role players in the Kunene region to regulate livestock numbers and grazing patterns to preserve the natural vegetation and prevent the calamity of a man-made drought.

The Soil Conservation Act enables the of agriculture minister through his agent, the Directorate of Animal Production, Extension and Engineering Services to intervene, reduce livestock numbers, enforce planned grazing that enables grass to recover and even evacuate certain areas completely to protect the soil and the grass sward it nurtures, obviously in collaboration with local and traditional leadership structures. What more do you need to protect the soil and its grass sward?

But this Act is not applied. As a result, cattle spread all around freely, graze where they want to, never give the grass a chance to recover and cause their owners hunger even this year, when it rains a lot in northern Kunene, let alone during a climatic drought.

The Communal Land Reform Act empowers traditional authorities to regulate grazing in their area of jurisdiction, determine livestock numbers and grazing patterns.

They can even penalise the owners of trespassing cattle that invade their commonage from a neighbouring area. What more powers do you need to protect your commonage grazing?

But most traditional authorities are not even aware that they have these powers, let alone are they able to apply them to the benefit of the people they are leading. As a result of not regulating grazing, they lead their people straight into disaster.

So the first thing that should be done is to create awareness of these legal resources amongst the relevant stakeholders. Thereafter, grow competence to apply these powers to the benefit of rural communities. The people and structures are in place, but they need to become active in these fields, preferably under the energetic guidance of the Kunene Regional Council.

These measures will take time. It will be too late to save the situation this year, but maybe next year already it could be better.

Then there are a large number of technical solutions to address the perpetual fodder deficit. One of the most appealing is to establish cultivated pastures of indigenous grazing grasses on some of the fertile valley and floodplain soils near the Kunene river, using its water to strategically irrigate the fodder crop until it can sustain itself on rainfall only.

Move a majority of the cattle off the rangeland and onto vast pastures during the rainy season, allowing the veld to recover over a number of years. When the cattle are moved back onto the veld in winter, their movement has to be controlled to follow a sensible grazing pattern.

The good rains received since independence have made us complacent. We have run down our reserves, depleted our resilience. Perhaps this year’s pending disaster will shock us into action? If not, perpetual poverty looms in the future.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!