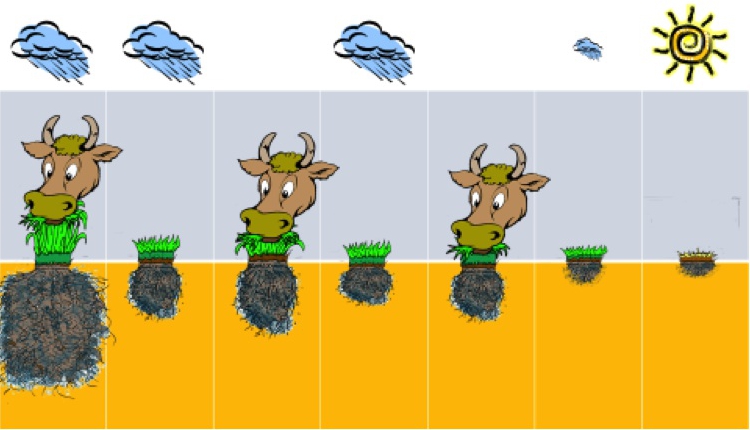

AXEL ROTHAUGECONTINUOUS and overly-frequent grazing during the rainy season (top picture) can kill perennial grasses within 2-3 years.

Grazing management is of a atmost importance during the rainy season, when grasses are growing actively. Once perennial grasses become dormant in winter, grazing hardly affects them as they are not metabolically active.

Summer provides moisture and the mineralisation of plant nutrients that fuel grass growth. They are absorbed by grass roots and circulated through the tuft. A big, strong root system can absorb much soil moisture and nutrients resulting in plentiful vegetative growth.

The aim of grazing management in summer should be to help grasses grow a big root system, but we cannot see below-ground. Thus, we use above-ground clues to guess when the root system is large enough to allow grazing of grass tufts without ill effects.

I am not aware of specific research on when a perennial grass plant is ready for re-grazing, probably because grazing readiness is a complex condition influenced by multiple factors difficult to reduce into a single experiment. In principle, a perennial grass plant is ready to be grazed again when it flowers and makes seeds. A perennial grass lives for many years. Its roots and tillers are replaced annually and are only a year old but the organism itself, the tuft, is around for a long time, even for centuries. In all these years it only takes one seed to establish itself successfully to replace the mother-plant and ensure generational continuity.

Making seeds is a costly metabolic process that requires lots of starch energy. A tuft can only make energy available for seeding if it has accumulated enough starch reserves. Thus, if a perennial grass flowers, its reserves must have been replenished, its root system must have recovered and it is ready for grazing without fear of damage.

Flowering is the clue that re-grazing can occur.

In full flower, grass contains marginally fewer nutrients than when younger. Graziers who prioritise animal nutrition re-graze perennial grasses before they flower, to ensure best forage quality for their livestock.

This weakens the grass tuft but as long as it rains well, it does not seem to matter.

Once moisture becomes limiting in below-average rainy seasons, these harshly utilised tufts die off easily. This is often seen on farms where efficiency of grass utilisation is maximised.

Repeatedly grazing perennial grasses before they flower wipes them out once the rains fail. Their starch reserves are just too depleted to survive harsh grazing and dry conditions.

A perennial grass tuft should not be grazed down to ground level. This may remove some of its basal buds (growth points) that could have developed into tillers, delaying recovery.

A grass tuft grazed very short takes several weeks longer to re-grow than a less harshly grazed tuft and the grazier loses grass production accumulated over a season.

Allow 5-10 cm of stubble on the tuft to facilitate faster re-growth after grazing. This level of grazing should be achieved within 10-14 days in summer so that the animals are removed to a different grazing area before serious re-growth starts and the “second bite” that is so damaging happens.

In winter, when perennial grasses are dormant, there is no re-growth after grazing and the tuft cannot be damaged by harsh grazing, unless desperately hungry animals dig it out with their hooves to consume it roots-and-all. Again it is advisable to leave 5-10 cm of stubble on the tuft to shade it and prevent radiation damage to the dormant buds.

In summer, allowing perennial grasses the time to recover from grazing until they flower and make seed maintains their present vigour and their current abundance, i.e. it maintains the status quo.

Grazing flowering grasses prevents mature seed from being produced and the grass population will not expand. To expand the population of perennial grasses to make more grass, requires a longer recovery period after grazing.

Grass rest will have to be extended until seeds mature, fall off the plant and add fresh seeds to the soil seed bank. Seeds germinate and establish in subsequent seasons only if climatic conditions are conducive and are facilitated by light grazing. Growing more grass is thus a variable and multi-year process.

Therefore, utilisation grazing management preserves the current condition of the grass sward, and restorative grazing management makes for more grass over a number of years.

The grazier has to correctly identify and apply that type of grazing management needed by his rangeland and farming enterprise in any specific year.

For example, applying utilisation management when the grass sward needs restoration damages perennial grasses and shrinks the carrying capacity of the farm. It makes for rich fathers but poor sons. Unfortunately, Namibian rangelands are currently mostly in the “poor son” phase.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!