The influx of migrants across the southern US border has become a critical factor in the US presidential election. But what is little known is the role of drug cartels in making a dangerous journey across Mexico even more perilous.

With its strip clubs, taco stands and buzzing motorbikes, San Luis Rio Colorado is typical of Mexican border communities.

In a migrant shelter, a stone’s throw from the towering, rust-red fence that separates the town from the US state of Arizona, Eduardo rests on a shady patio.

On one wall, there’s a large wooden cross. And it’s here that Eduardo began to process – and recover from – his terrifying ordeal in Mexico.

Eduardo, who is in his 50s, used to run a fast-food restaurant in Ecuador. But organised crime has tightened its grip in his former, mostly peaceful, South American home.

“As business people we were extorted,” he says. Eduardo was threatened with death if he didn’t pay a ‘tax’ to the gang. “What could we do? To save our lives we had to leave.”

Eduardo never wanted to migrate, but he was frightened and decided to head to the US to ask for asylum.

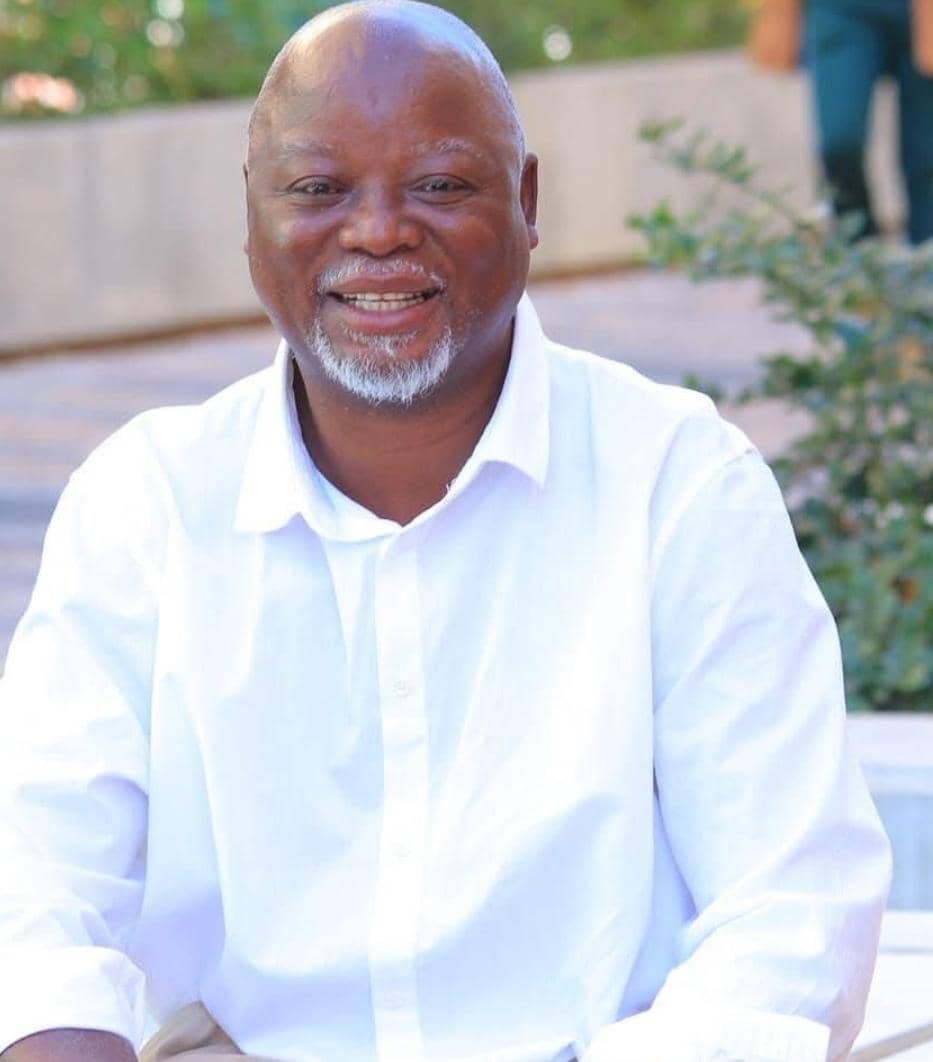

Eduardo at the migrant shelter in San Luis Rio Colorado

His story is typical of thousands of people from many parts of the world fleeing violence and seeking a new life in the US.

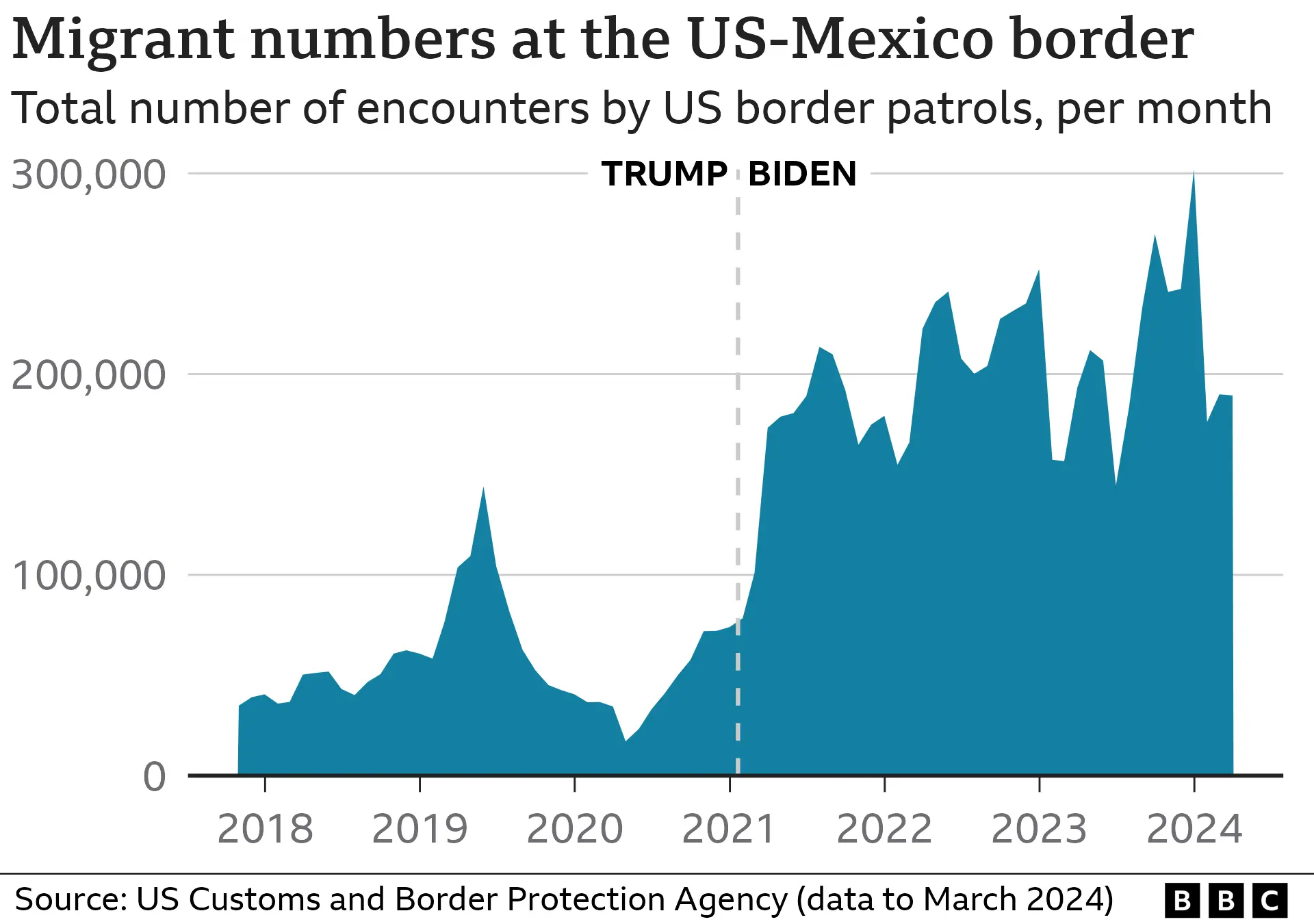

After a record number of arrivals at the end of 2023, Democratic President Joe Biden proposed stricter immigration measures which include shutting the border when it’s overwhelmed. His opponent Republican Donald Trump says he will introduce mass deportations if elected in November.

What has stayed mostly under the radar in the debate about mass migration to the US is the role of Mexico’s deadly drug trafficking organisations.

Eduardo began his journey by flying from the Ecuadorean capital Quito to Mexico City. Then he boarded a bus north to Sonoyta on the US border, a journey of more than 30 hours.

The passengers were a mix of migrants and Mexicans. But what Eduardo didn’t appreciate was that his trip would take him across terrain controlled by some of Mexico’s most violent drug cartels and their associates – malevolent forces that dominate the business of migration.

The first time the bus was stopped, it was early morning, around 6am. Ten armed men wearing balaclavas got on board.

The bus was driven off-road towards the mountains. The men asked to see everyone’s papers. Once they established who the migrants were, they asked each of them for 1500 pesos (US$90) or they would be detained.

The migrants pooled their cash but were short by 200 pesos (US$12). The men let them off and 11 hours after being stopped, the bus was allowed to go on its way.

San Luis Rio Colorado, the border town where Eduardo recuperated at the migrant shelter, has also gained a reputation for the kidnap of migrants.

In May last year, neighbours of a modern, two-storey house on the edge of town reported unusual comings and goings. When the Mexican authorities swooped, five people were arrested and more than 100 migrants freed. Some of them had been held in the house for three weeks.

“They didn’t have food and water, and they were maltreated physically and psychologically,” says Teresa Flores Munoz, a local police officer involved in the operation.

She remembers a woman from India. “She was crying and holding her baby. She pushed the baby at me – she said I should take him, because they were going to kill him. It was really desperate.”

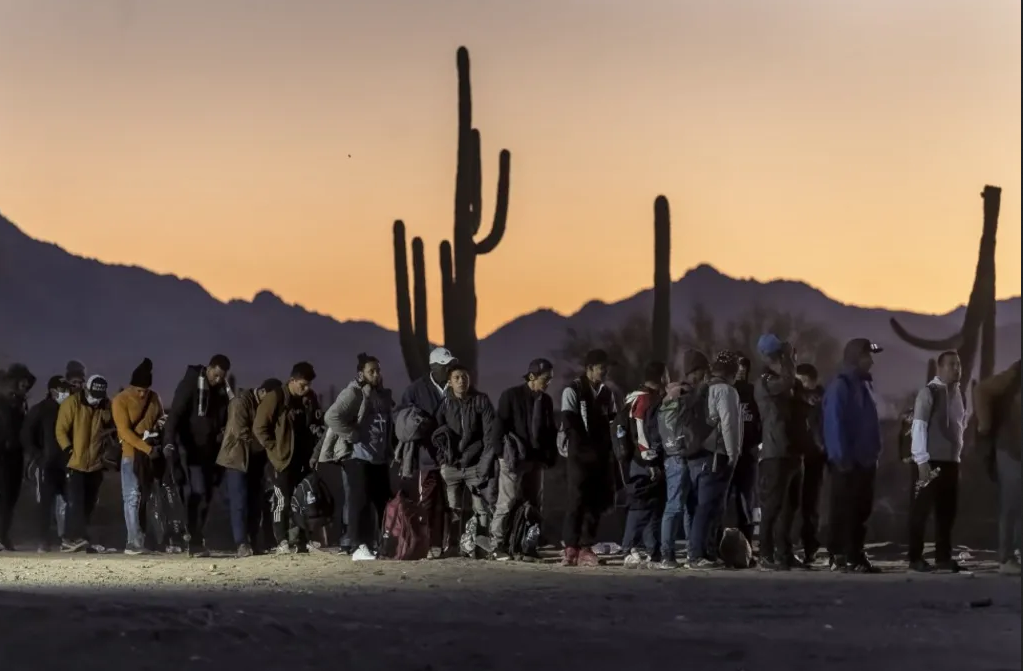

US border patrol pick up migrants at Yuma

Twenty-three nationalities were represented among the captives, including people from Bangladesh, Uzbekistan, China, Mauritania and Senegal.

According to local reports, the kidnappers demanded US$2,500 from each migrant, double from pregnant women.

If the migrants do not have the money, the gangs demand it from relatives either back home or north of the border in the US.

These extortionists and hostage-takers are not only professional criminals – some are also law enforcement. As Eduardo’s bus continued north through the Mexican states of Sinaloa and Sonora, he says they were stopped at six police checkpoints where officers demanded money from the migrants.

“If you didn’t have cash they called you over. They said, ‘take off your trousers, take off your clothes’, and you have to give them everything, like your suitcase. If you didn’t have money they took your papers – that’s how I lost some documents.”

Photos taken secretly on a bus raided by armed men

Photos taken secretly on a bus raided by armed men

Bus holdups targeting migrants aren’t unusual. In San Luis Rio Colorado, we worked with a local Mexican journalist. After he left us, he sent us photos, taken secretly, of his bus home being stopped by a gang, their faces covered.

“Everyone on the bus knew they were sicarios [hitmen] for the drug and migrant trafficking mafia,” he said.

The masked men only questioned people they suspected weren’t Mexican – those in poor clothing, their faces fearful. The five or six migrants taken off the bus were each extorted of up to US$50.

The door of the men’s truck bore the logo of an agency of Sonora’s State Prosecutor – AMIC (Agencia Ministerial de Investigaciones Criminales) – can be seen. Our journalist colleague thinks it was faked.

Eduardo’s most distressing experience on his journey from Mexico City north to the border happened in the state of Sonora too, around three hours from Sonoyta.

Again, the bus was stopped by armed men. And because there was not enough cash to hand over, two Colombian families, including five children, were forced off the bus, loaded into a truck and driven away.

“We didn’t have enough money to save everyone,” says Eduardo, his voice breaking.

He was now penniless, his $3,000 savings gone. This meant he couldn’t pay a “coyote” or people smuggler in Sonoyta to get him across the border illegally into the US.

The bus driver told Eduardo he risked being kidnapped if he stayed there, and dropped him in San Luis Rio Colorado instead, where Eduardo made his way to the migrant shelter.

Abducted migrants, or those who refuse to pay the men with guns, may face a terrible fate. Further west along the border, the city of Tijuana has been a jumping off point for people entering the US illegally for decades.

And recently, bodies of migrants have been found in the hills east of the city – shot in the head, execution-style. There is speculation they were people who tried to make it onto American soil without paying a “coyote” or the criminal group that controls that part of the border.

What is evident is that the cartels have diversified their economic activities to include extortion, kidnap and human smuggling, says Dr Victor Clark Alfaro, a professor at San Diego State University.

Border at Tijuana

“I call them ‘narco-coyotes’ because they not only cross people, they also cross drugs into the US,” he says, adding that migrants can be forced to take narcotics with them.

In Tijuana, the infamous Sinaloa cartel controls groups of human smugglers and so does the Jalisco New Generation cartel.

“Violence is one of the key elements of organised crime,” says Dr Clark. “Violence used to control their own territories, and against innocents.”

In San Luis Rio Colorado, Eduardo rested, felt better and got a local job. But after his journey from hell across Mexico, he chose not to risk an illegal crossing into the US with a “coyote”.

Instead, he registered with a free, US government online app called CBP One which allows migrants to schedule an appointment at a US Port of Entry.

Getty Images

Getty Images

If they pass security screening, they may be paroled into the US and allowed to work while they wait for an immigration hearing. This is one of the Biden administration’s measures designed to dilute the power of the cartels.

Two things have kept Eduardo focused on making it to the US. One is his Catholic faith. The other, some very unwelcome news from Ecuador about a friend, who – like Eduardo – was being extorted by criminals.

Eduardo had wanted the two of them to travel north together. But his friend didn’t want to leave family – he told Eduardo he would fix things with the gang. He couldn’t.

“The men went to my friend’s shop. They killed him there,” says Eduardo, in tears. “So, if I’d stayed in Ecuador… Well, I give thanks to God… I’ve suffered, but I’m still alive.”

In March, Eduardo entered the US legally.

BBC photos by Tim Mansel

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!