JAIL terms that exceed the expected lifespan of long-term prison inmates are not constitutional in Namibia, the Supreme Court ruled in a landmark judgement yesterday.

Sentences of imprisonment for such a long period that it would leave the sentenced offender without a realistic hope of ever being released from prison amount to cruel, degrading and inhuman punishment and infringe the prisoner’s constitutional right to human dignity, judge of appeal Dave Smuts found in a judgement on four long-term prison inmates’ appeal against the jail terms to which they were sentenced in February 2002.

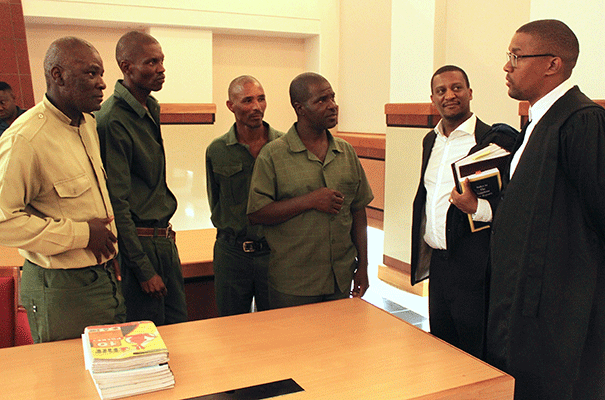

Judge Smuts, with four other appeal judges agreeing with his judgement, set aside the sentences of 30 years’ imprisonment on each of two murder charges that Zedekias Gaingob, Erenstein Haufiku, Salomon Kheibeb and Nicodemus Urikhob received at the end of their trial in the Windhoek High Court, and replaced those with two sentences of life imprisonment for each of the men.

The Supreme Court ordered that the two life prison terms should run concurrently, and are backdated to February 2002.

The effect of the Supreme Court’s decision is that having now been sentenced to life imprisonment, the four men would have to serve 25 years of imprisonment, counted from February 2002, before they would become eligible to be considered for release on parole.

Gaingob, Haufiku and Kheibeb were each sentenced to an effective jail term of 67 years, while Urikhob was sentenced to 64 years’ imprisonment, after they had been convicted of having robbed and murdered an elderly couple in a night-time attack at a farm in the Okahandja district in April 2000.

In terms of Namibia’s Correctional Service Act of 2012 and a regulation published under that law, someone sentenced to life imprisonment after 15 August 1999, which was when the previous Prisons Act came into force, would be eligible to be considered for release on parole or probation after serving at least 25 years in prison without committing or being convicted of any crime or offence during that period.

Someone not sentenced to life imprisonment, but instead given a jail term of twenty years or longer, would in terms of the law become eligible for release on parole or probation after having served two-thirds of their sentence.

The prison terms to which the four appellants were sentenced were in effect more severe than life prison terms, judge Smuts remarked. He noted that, with jail terms of 67 or 64 years, the men would have been eligible to be considered for release on parole only after 44 and a half years or 42 and a half years in prison, respectively.

Those sentences effectively left the four men – aged between 22 and 36 at the time of their sentencing – without a realistic hope of being released during their lifetimes, judge Smuts said.

He added that it appeared the sentences imposed on the four appellants were intended to circumvent the parole provisions that the parliament determined as appropriate. Such an approach of imposing excessively long sentences to circumvent a prisoner’s right of having the hope of an eventual release from jail conflicted with the offender’s right to dignity, judge Smuts said.

The crimes that the four men committed were “brutal and vicious in the extreme”, and justified that they had to be permanently removed from society by being sentenced to life imprisonment – however, while still left with the hope that they could be considered for release on parole after serving 25 years of their sentences, judge Smuts also stated.

Both judge Smuts and acting judge of appeal Theo Frank, who wrote a concurring judgement, pointed out that an effective sentence of 37 and a half years’ imprisonment would mean that an offender had been sentenced to a jail term that was harsher than life imprisonment.

Such prison terms of more than 37 and a half years could rightly be described as inordinately long and were thus liable to be set aside, judge Frank said.

Both judges also noted that the parole board would have to be satisfied that someone serving a life prison term would not re-offend and would be likely to lead a useful, responsible and industrious life before deciding to release the prisoner on parole.

Chief Justice Peter Shivute, appeal judge Elton Hoff, and acting judge of appeal Yvonne Mokgoro agreed with judge Smuts’ judgement.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!