South Africa – a country plagued by the Tartarean past of apartheid that sought to tear down, rip apart and destroy through the name of segregation and ‘racial purity’.

During this period of racial segregation, the battle between black and white made headlines and attracted worldwide attention.

Cape Town, like many other South African cities, felt the impact of the Group Areas Act of 1950, particularly in the vibrant, multi-racial neighbourhood of District 6.

Assigned a whites-only area by the government, the rest of the residents, most of whom were Coloured, were relocated in the barren areas of the Cape Flats with their homes, heritage and memories all left for ruination.

Out of this ash, a hero was born.

On 17 October 1966, Ivy Kriel gave birth to Ashley James Kriel – a baby boy that would in his short life, impact the visibility of his peers and the narrative of the Coloured youth in the Cape Flats during the apartheid struggle.

The only son of Ivy and the late Melvin James, Kriel was the also the youngest in the family after his sisters Michel Assure and Melaney Adams.

He was a natural-born leader, as described by those who remember him. He had a knack for mathematics, science, and strategic thinking displayed by his prowess in a game of chess. These traits made Kriel the quintessential spearhead in the vanguard of pupil protests and political involvement at Bonteheuwel High, where he completed his school career in 1985.

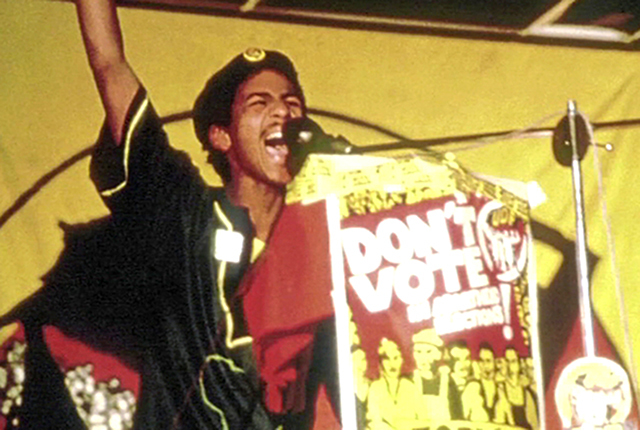

Despite being a teenager, Kriel, as an eloquent public speaker and coordinator, became influential in the Bonteheuwel area with his involvement with the Bonteheuwel Inter-schools Congress (Bisco) and the Bonteheuwel Youth Movement (BYM), where he organised school boycotts, protests and other activities of rebellion in line with the African National Congress (ANC)’s defiance towards the apartheid government.

Along with fellow pupils Anton Fransch, Andrew ‘Gorrie’ November, Coline Williams and Gary Holtzman, Kriel became a target for the apartheid security police for his contribution to the anarchy in Bonteheuwel.

Due to the vigorous surveillance from the security police, on 27 December 1985, Kriel was forced to go underground – a pathway that would see him grow from a juvenile into a man. During this period he became part of the ANC’s armed wing, uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK), where he was helped to move across borders and finally ended up at an MK training camp in Angola.

While at camp, Kriel became proficient in isiZulu, trained in the use of various small arms and the making of homemade explosives, as well as close-quarter, unarmed combat. He quickly rose in the ranks, later leading the Ashley Kriel Detachment (AKD).

Anti-apartheid dignitaries Joe Slovo and Chris Hani, reluctantly sent him to South Africa in 1987, when he was 20 years old.

Entering the country via Lusaka and Gabarone, Kriel was unable to make contact with his family due to security reasons and he took up a place of residence in one of his old teacher’s home in Athlone.

At the tender age of 20, many youngsters, still finding their feet, have hopes and dreams of a bright future, of travelling, finding love and building families.

Ashley Kriel, did not have that luxury.

On 9 July 1987, answering a knock on the door, believed to be municipal workers, Kriel was arrested by the security police, shot in the back, and died at a house in Hazendal, Athlone.

Captain Jeffrey Benzien, member of the Bonteheuwel unit of the security police claims Kriel had a gun under a towel when he answered the door, which conveniently went off while they were trying to handcuff him.

Independent forensic investigator, Dr David Klatzow, refutes these events, claiming the gunshot wounds were not close-contact but rather consistent with a shot fired from a distance, while Kriel was handcuffed. His sister Michel, who returned to the house, found blood inside and outside, including on a spade. She believes he was tortured. Benzien was granted amnesty for the death of Kriel through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

Ashley James Kriel – a name not often mentioned in the media, history books or by politicians and historians who have ‘black-washed’ the anti-apartheid struggle, was a beacon of hope and a hero for the Coloured youth not only in Bonteheuwel, but across all plains.

On his release from prison in February 1990, Nelson Mandela acknowledged Kriel’s sacrifice for the anti-apartheid struggle.

Today we remember the selflessness of the ‘Che Guevara of the Cape Flats’.

With additional information from sahistory.org.za and actionkommandant.co.za.

– @JonathanSasha on social media.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!