ACCRA–When it opened in 1963, Ghana’s oil refinery symbolised pride and hope for the first African country to escape colonial rule. Now the plant stands idle in a sign of the economic shadow that has crept over one of the continent’s brightest stars.

The discovery of oil in Ghana in 2007, added to its gold and cocoa wealth and its other major asset, stable democracy, gave it a chance to start catching up with oil giant Nigeria and regional West African economic powerhouse Ivory Coast.

The year after oil began flowing in 2010 economic growth spiked to 14,8%, one of the highest rates in the world.

Now, however, the country faces high levels of public debt, a currency that has fallen sharply, a yawning budget deficit and inflation that recently rose as high as 17%.

Chronic power shortages have led to lengthy rolling blackouts, angering voters and raising business costs.

The growth that propelled Ghana to official ‘middle income’ status in 2010 is forecast at a modest 3,9% this year, lower than the average for sub-Saharan Africa.

Economists say Ghana’s prospects are still bright over the medium term but only if it quickly restores fiscal stability.

The 45 000 barrel-a-day Tema Oil Refinery east of Accra is a case in point: it played a key role in Ghana’s oil sector for decades, but was subsidised by the government. In practice some of those payments were not made, leaving it in debt.

A mechanical fault has now put it out of action for a month.

To stabilise the economy, the International Monetary Fund last week agreed to a US$918 million aid programme that also aims to help increase tax collection and strengthen central bank policy.

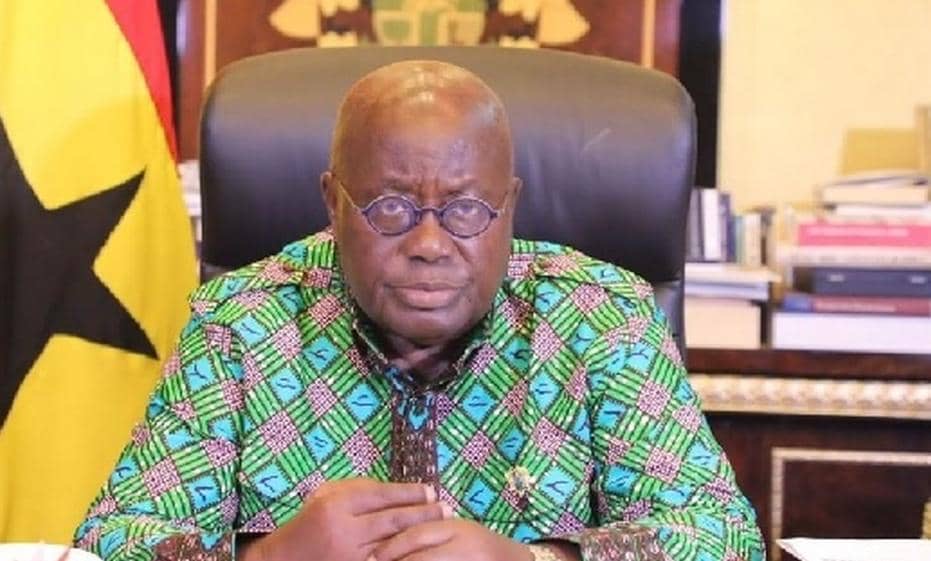

The sagging economy presents an opportunity for the opposition New Patriotic Party, whose leader Nana Akufo-Addo blames the National Democratic Congress government for the problems.

Akofo-Addo lost narrowly to president John Mahama in 2012 and is set to run against him again next year in what is likely to be a close election between two parties with government experience and similar ideological stances.

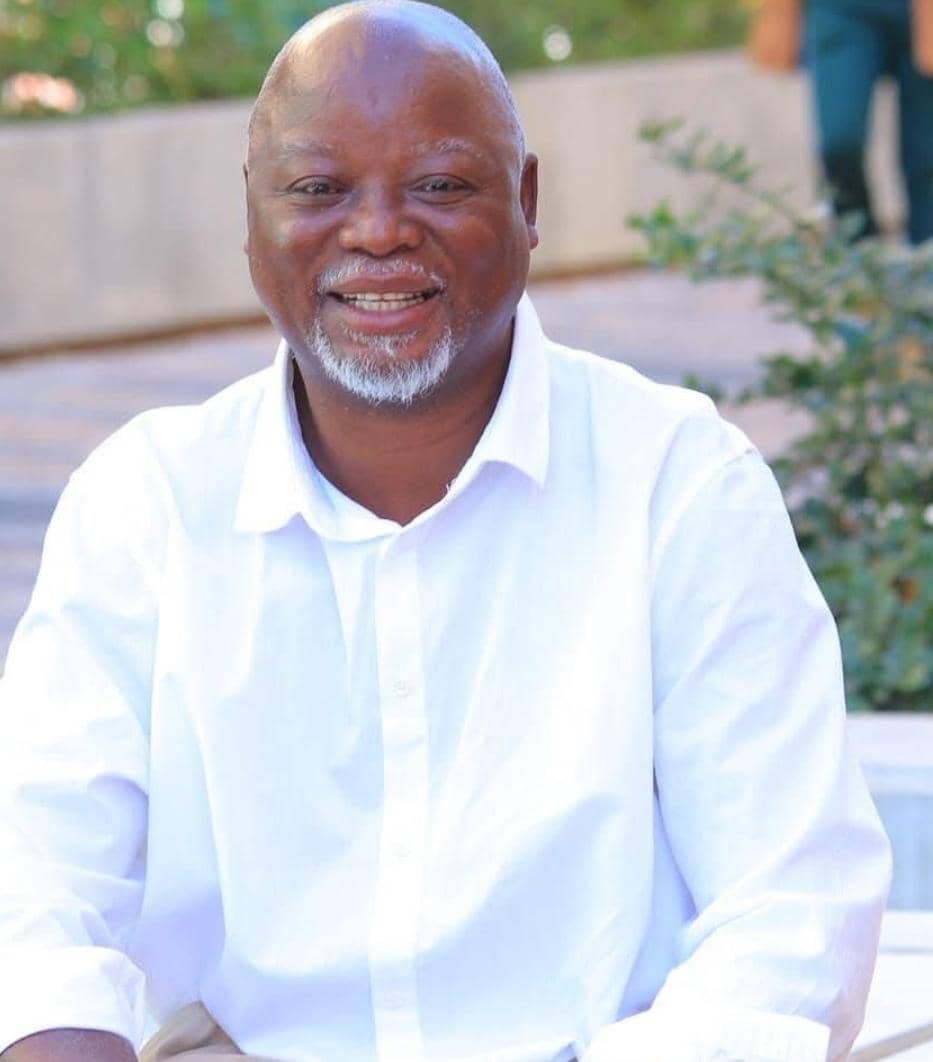

Mahama’s government defends its record and says mid-term prospects are healthy as fresh oil and gas finds come on stream from two offshore fields in the next few years.

The IMF deal is key to a plan to secure a bridge financing loan in the first half of this year followed by a Eurobond. It should also help unlock donor budget support.

But investors and economists say it is not a fail-safe route back to fiscal health.

“It will depend on implementation,” said Moody’s analyst Elisa Parisi-Capone. “We need to see how authorities progress in terms of fiscal consolidation.”

Ghana has struggled to implement past IMF programmes, especially in the run up to elections. Public sector wages ballooned in the 2012 election year, pushing the budget deficit to a huge 12% of GDP.

Moody’s downgraded Ghana’s sovereign rating last month in a move that took into account the IMF agreement. At the same time, the deal requires civil service reform to reduce the wage bill – a move that could lead to conflict with powerful unions.

With all that, the irony of the refinery breakdown may be how little it will be missed by an economy that has shifted radically from the state-dominated vision of Kwame Nkrumah, elected Ghana’s first president after independence from Britain in 1957.

Most of Ghana’s fuel needs these days are imported as finished product, not crude, and the refinery processes none of the roughly 100 000 barrels per day of oil produced by the Jubilee offshore field, operated by Britain’s Tullow.

Last year, the refinery processed just 18% of Ghana’s 3,7 million metric tonnes of fuel imports, according to Ghana Chamber of Bulk Oil Distributors figures.

– Nampa-Reuters

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!