Stacy Herbert chats to The Namibian about being diagnosed with type I diabetes, recalling how her heart sank as she was briefed on the condition.

Not knowing much about the disease, Stacy Herbert’s heart sank as her doctor briefed her on the condition.

“Your pancreas is producing little or no insulin. Insulin is a hormone that is used by the body to allow sugar (glucose) to enter cells to produce energy. It has no cure.

“You have to manage the amount of sugar in the blood using insulin, and monitor your diet and lifestyle to prevent complications,” she recalls vaguely hearing the nurse who was counselling her say.

Herbert (37) says her mind was racing with the possibility that she might die, her limbs may need to be amputated and that the condition could affect her chances of having a baby.

The then-29-year-old former primary school teacher visited the doctor in 2015 when she started experiencing blurry vision, fatigue and excessive thirst.

“I visited one doctor who performed a series of tests. He told me that I had borderline diabetes, but that I was still safe. I was advised to improve my diet and exercise a bit.

“He also prescribed sachets of energy powders to dissolve in water. It made things worse. I drank a lot of energy drinks, as I did not have the right information,” she says.

Feeling weak a few months later, Herbert visited another doctor, who once again did a blood glucose test.

“The staff were quite shocked and wondered how I still managed to stand, as my sugar level was really high. By then, I had consumed a lot of sugary drinks. I was frequently thirsty.”

She describes receiving her diagnosis as feeling like a death sentence.

It was all the more devastating because her grandmother died from the condition.

“I never realised it could happen to me. I was immediately put on insulin and tablets.”

NEW REALITY

Herbert says it took time to get used to a new regime of taking insulin and tablets, monitoring her blood sugar, changing her diet, and eating at certain times.

“I lost a lot of weight, as my fat cells were being attacked rapidly. I eventually learned to manage it. It is still hard after all these years, but I get by.”

As someone who really loves her food, especially potatoes which she can no longer indulge in, Herbert says this aspect of her diagnosis was particularly challenging.

“I now drink a lot of water and sugar-free drinks. People have a tendency to eat exactly what they are forbidden to eat, but you need to obey the doctors’ orders to survive,” she says.

In coming to terms with her new reality, Herbert decided to start helping others, especially children, after discovering there were pupils at Flamingo Primary School, where she taught at the time, who also lived with type I diabetes.

“I decided to be a support system to children and their families. This illness is much worse on children. They have to learn about injections at an early age, and it is really painful.

“They cannot eat what their friends are eating, or whenever they want to, and they can fall into a coma quickly,” she says.

When starting her initiative, Herbert asked doctors, dieticians and people in the community for information on children who had been diagnosed with type I diabetes, and approached some parents who were struggling to afford medication.

She says she has donated blood glucose testing/monitoring machines to five schools and 10 children, as well as five others in hospital since initiating the project. Herbert also kept high-sugar carbonated drinks in the school’s fridge in case of an emergency involving one of the pupils.

“I also dedicated time to explain to staff at school what symptoms to look out for in their pupils,” she says.

Soon, she started educating the staff and pupils at other schools about the condition through workshops and information sessions.

A COSTLY CONDITION

Herbert says she could empathise with some parents of children with diabetes who could not afford the medication, those who did not have medical aid, or those whose medical aid funds had been exhausted by the cost of treatment.

She then decided to write letters to five schools at Walvis Bay to help organise fundraising events.

“Daily insulin injections and pumps can be very expensive.

My fundraising activities started with a day on which pupils and teachers had to wear denim and donated N$5.

“The money was used to buy diabetic care packages, which included blood sugar monitors, bracelets, test strips, as well as notebooks for children with type I diabetes to record their blood sugar readings,” she says.

Herbert says the project also raises awareness through pamphlets and handing out medical alert wristbands to children with diabetes, which include emergency contact numbers.

Former Flamingo Primary School principal Ursula Damens says she welcomed the project as it was a learning experience.

“I really welcomed the idea when she first started talking about it. I did not think of it just as a fundraiser, but as an educational experience for the staff and the pupils.

“Pupils and teachers started coming on board immediately to support the initiative.”

Robin du Toit is one of the beneficiaries of a wristband donated to her son, Coden.

She recalls being afraid when she was first informed of his diagnosis.

“He was only four years old in 2019 when he started feeling sick.

We were told he has type I diabetes. He was in hospital for about three weeks. I was really shocked because he was so young,” she says.

Coden, who is now nine years old, was informed of his illness and gradually grew accustomed to his condition.

He says he has learnt to cope with the condition.

“I have learnt to accept my fate and live with diabetes. It is mostly not hard to stay away from some foods, but sometimes I long to eat snacks like ice cream when my friends eat it.

“There are days when I do not feel well, although not too often.

The teachers usually inform my mother, who fetches me from school. I also learned to play safely so I do not get hurt,” he says.

Du Toit says: “It is a costly situation that needs injections, monitoring machines and insulin pens, among other things.

We are sometimes referred to buy the medication at a pharmacy, when the [state] hospital runs out of medication.

“I spend over N$1 000 on medicine because I do not have medical aid.”

The wristband Herbert has donated provides a sense of comfort, she says, because it includes Coden’s details in case of emergency.

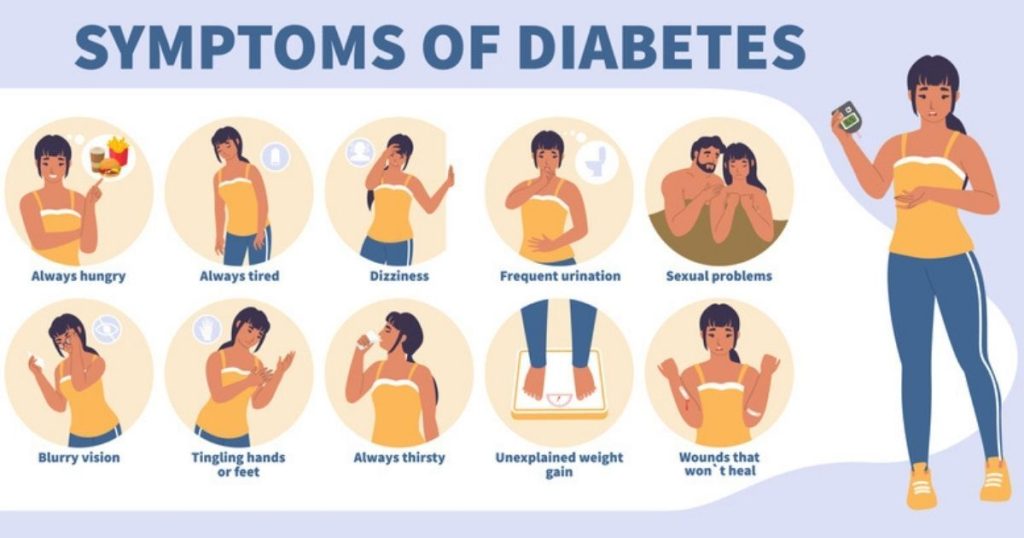

SYMPTOMS

Namibian optometrist Nadine Kruger, who currently works in Ireland, says diabetes affects the blood vessels, which causes blurry vision.

“When you visit your optometrist, they will look at the back of your eye, the only place in the body where you can view the blood vessels. Optometrists will often pick up changes in the blood vessels and refer you to get your blood sugar levels checked,” she says.

She says routine eye tests usually take place every two years, but for those who have diabetes, it is recommended to have eye tests done annually.

“The best way to view the blood vessels at the back of the eye is to get a dilated retinal exam, where they put drops in the eye that temporarily enlarge your pupil so they can have a better view of all the retinal blood vessels.

“You are also more at risk of getting glaucoma and cataracts if you have diabetes,” Kruger says.

Type I diabetes symptoms include weight loss, and an increase in infections in children, as well as heavier nappies in babies.

Parents of children with symptoms of diabetes are advised to take them to the doctor for a blood glucose test.

- • In 2021, over 537 million adults (20-79 years) globally were living with diabetes, which is one in 10 people.

- • In Africa, one in 22 adults (24 million) people are living with diabetes. This figure is predicted to double to 55 million by 2045.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!