PetroSA has chosen Equator Holdings, run by notorious political operator Lawrence Mulaudzi, to bankroll exploration of its offshore gas reserves and rebuild critical gas infrastructure — a project that sits at the heart of government’s multibillion-rand gamble on gas.

On 11 December 2023, the Petroleum, Oil and Gas Corporation of South Africa (PetroSA) held a two-hour press conference to try to defend its R3.8-billion deal with Russia’s Gazprombank.

If the experience was bruising, it did not show.

Just hours later, the same officials held a private signing ceremony to cement a deal that is far bigger and more dubious with politically connected businessman Lawrence Mulaudzi.

Mulaudzi was a key character in the Mpati Commission’s investigation into corruption and malfeasance at the Public Investment Corporation (PIC) – his name is mentioned 176 times in the final report.

He has also been accused of channelling money to a company linked to EFF deputy president Floyd Shivambu, and a trust linked to former ANC treasurer Zweli Mkhize.

The deal, quietly inked on 11 December, gives Mulaudzi’s company, Equator Holdings, the mandate to fund and rebuild critical gas infrastructure that is at the heart of government’s multibillion-rand gamble on gas.

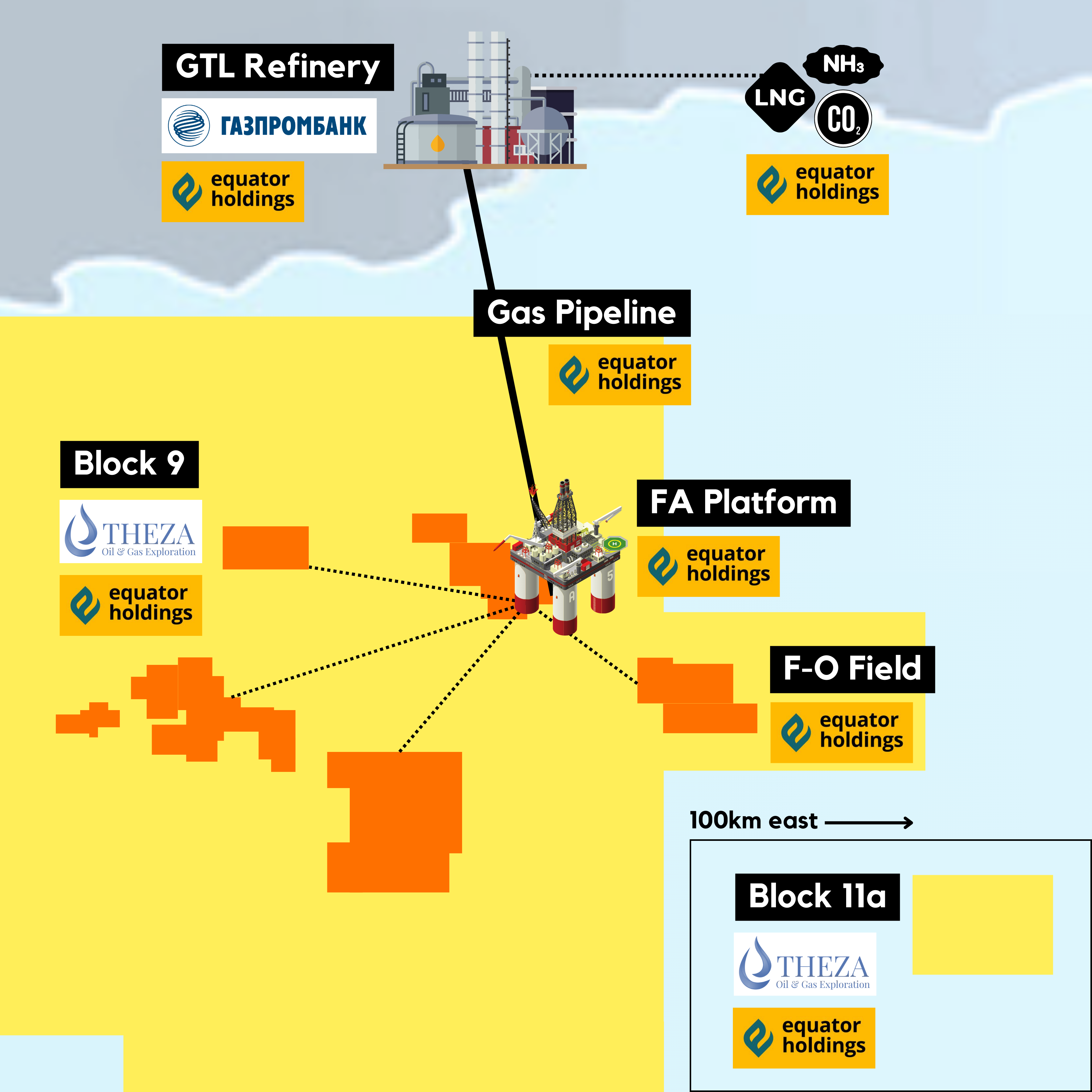

This includes refurbishing the FA offshore platform – which connects offshore gas to pipelines that bring it onshore – and the gas portion of PetroSA’s Mossel Bay refinery.

PetroSA confirmed that in each of these cases, Equator will both fund and execute the projects.

It is unclear where Equator will find the money. Mulaudzi’s own finances are precarious: Absa previously seized his Bentley and last year obtained two debt judgments against him totalling R2.8-million; his former landlord Aucap tried to repossess his Camps Bay home over unpaid rent.

But Mulaudzi brushed aside all criticism: “We are… pleased as a company to enter into this partnership with PetroSA which will provide security of gas supply and unlock infrastructure bottlenecks in the energy space for [the] South African economy,” he said in a two-page letter sent on behalf of the company.

“Although we cannot disclose the details of the transactions as we are bound by legal confidentiality provisions, we can confidently state that Equator Holding[s] complied with PetroSA requirements… We have every intention to deliver, and we will!”

Full marks for confidence, but a closer look at the deal suggests that PetroSA appointed Equator without any evidence that it had either the money or technical skills for a project of this scale, raising serious doubts about the probity of the process.

The first tender

In January last year, PetroSA issued three tenders: one was to restart the gas-to-liquids (GTL) refinery in Mossel Bay, which was eventually awarded to Gazprombank Africa.

The other two tenders focused on PetroSA’s offshore gas fields, which until 2020 provided the feedstock for the GTL refinery.

RFP 0003 was to appoint a technical partner who could restart the wells and drill new ones in the turbulent oceans off the Eastern Cape, while RFP 0004 was a funding-only version of the same project.

By mid-2023, PetroSA had selected preferred bidders for the two overlapping tenders: Theza Oil & Gas wanted to drill the wells using its own funders (RFP 0003), while Equator Holdings – Mulaudzi’s company – wanted to fund the deal (RFP 0004), which PetroSA estimated could cost $1.2-billion (R21.6-billion).

It is not clear how Equator qualified. The tender was explicit that any successful bidder “must be an established player, or credible financial institution” to avoid being eliminated. Equator was neither.

The company was registered in 2018, but has no website and no track record we could find in the financial sector or energy space; to the extent it operates, it appears to do so from Mulaudzi’s Sandhurst home.

In fact, Equator had submitted a bid for RFP 0001, the tender that Gazprombank bid for and won, but it scored 0 out of 100 and was disqualified because the “[a]uthenticity of entity could not be established”.

Another “elimination criteria” of RFP 0004 was that bidders had to demonstrate “sufficient funding to support [the] proposal”. This, the tender suggested, should be in the form of an “indicative term sheet or letter, outlining at least success fee, interest rate, duration, maximum funding and any other material conditions”.

Equator had secured a letter of intent from the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC) suggesting it may be willing to invest up to R1-billion in the project – once it had evaluated the project and done a due diligence. But this is far more preliminary than the term sheet the tender required.

A spokesperson for the IDC confirmed that “[t]he IDC did not issue a term sheet to… Equator Holdings.”

Unfazed, PetroSA selected Equator as the preferred bidder to bankroll the R21.6-billion expansion of its upstream gas assets.

“The Evaluation Team evaluated the bids in accordance with the evaluation criteria that was published, and points were allocated accordingly. The Evaluation Team subsequently recommended Equator Holdings as the preferred partner,” PetroSA told us in a written response that failed to answer questions about the seemingly glaring gaps in the Mulaudzi bid.

Equator did not want to discuss specifics but told us: “We confirm that prior to the award, we submitted a detailed proposal to PetroSA, which we believe complied with all the set requirements. We also provided documents that were required in this bid.”

The ‘arranged marriage’

Predictably, PetroSA now had a problem. Two bidders had been selected to fund the same projects: Theza, which would execute and fund the project, and Equator, which would only fund it.

PetroSA’s alleged solution was to play matchmaker between Theza and Equator: “[PetroSA] said that they will, at the appropriate time, look at introducing the [other] party,” Theza’s chief executive and majority shareholder Barend Hendricks told us.

“They said they would like for us to see if there are synergies.”

In October, with or without PetroSA’s prompting, they formed EquaTheza: 90% owned by Theza and 10% owned by Equator.

A source within Theza put it more bluntly: “They were foisted on us… They don’t add any value to us as Theza.”

PetroSA denies this: “PetroSA did not pressure Theza to partner with Equator. Theza and Equator Holdings decided to form EquaTheza voluntarily on their own accord.”

Equator/Mulaudzi dispute the source’s claims as well: “Any other relationships that have been formed… have been done so independently and voluntarily without the assistance of PetroSA…

“Allegations by you of ‘foisted’ relationships with any company not only undermine us as an entity but they are an insult to those companies themselves.”

The agreement struck between the new business partners was that Equator would support Theza in its efforts to secure financing from local development finance institutions such as the PIC, IDC, and the Development Bank (DBSA).

Hendricks confirmed that Mulaudzi had set up a meeting with the IDC to discuss funding but said it went no further, and that Theza had found funding elsewhere.

Despite this, Equator remains a 10% shareholder in the deal. Asked what he knew about his new business partner, Hendricks said: “Zero. I did not even Google the man. Up to today, I don’t know who the shareholders of Equator are.”

Echoes of PIC manipulation

The “arranged marriage” between Theza and Equator bears a striking resemblance to the Tosaco deal funded by the PIC, which made Mulaudzi infamous.

In 2015, Tosaco, the BEE partner of French energy company Total, was looking to sell its 25% stake. The PIC had been approached by two suitors: the Kilimanjaro consortium led by Mulaudzi and the Sakhumnotho consortium led by Sipho Mseleku.

The Mpati Commission, which investigated malfeasance and corruption at the PIC, would later conclude that then-chief executive, Dr Dan Matjila, had quietly engineered a union between the two consortia.

“Dr Matjila… testified that he was thinking that the two (Mr Mseleku and Mr Mulaudzi) should combine forces even if he did not say so,” the Mpati Commission report noted, adding: “[I]t is incredulous that his thinking can manifest into reality by accident… Simply put, real decision-making was effected outside of the PIC governance processes.”

The Tosaco deal was a perfect example of where things were going wrong at the PIC: R1.7-billion was approved to buy the 25% stake in Total, then another R100-million was tacked on – without proper approval – to cover “transaction fees”, including R80-million for Mulaudzi’s own company.

Once the deal had been approved, Matjila is alleged to have pressured Mulaudzi to give bogus loans to a young entrepreneur who had befriended then minister of state security, David Mahlobo.

“[A]t no point did I regard this as a loan,” Mulaudzi told the Mpati Commission. “This was based on the request made by Dr Matjila… there is no way I would have said no to the CEO of the PIC… as a businessman, you never wanted to be ostracised by Dr Matjila.”

AmaBhungane’s own investigation uncovered that a front company, controlled by senior PIC executive Paul Magula, was given a R24-million stake in Mulaudzi’s PIC-funded deal.

Read amaBhungane’s previous investigations on Mulaudzi: Leaked WhatsApps: How access to PIC execs may have facilitated deals and WhatsApps expose Floyd and the ‘Red Boys’

At the time, Mulaudzi claimed that his company had been “subjected to various offensive, unfounded allegations that intended to create a narrative that we as a company did not act ethically and properly in our dealings with the PIC”.

In its recent letter, Equator cast Mulaudzi as a star witness: “Mr. Mulaudzi fully cooperated with the commission… We believe that throughout that process, Mr Mulaudzi was transparent, truthful and forthright with the commission. Hence this was even acknowledged by commissioners after his testimony.”

It added that it “will not comment any further on matters that… are unrelated to the work that Equator Holdings is engaged in with PetroSA.”

This included the questions we posed about Mulaudzi’s proximity to politicians.

In 2018, the Mail & Guardian uncovered payments made by Mulaudzi to Grand Azania, owned by the brother of EFF deputy president Floyd Shivambu – payments that were made after Shivambu sent Mulaudzi WhatsApps pleading for “urgent interventions” ahead of his 2017 wedding.

An investigation by Daily Maverick further alleged that Mulaudzi had made a R5.9-million payment, after receiving a second PIC-funded deal, that was used to pay for a luxury townhouse registered in the name of a trust controlled by the ANC’s then treasurer, Zweli Mkhize.

Importantly, all this information was in the public domain when PetroSA selected Mulaudzi to bankroll the R21.6-billion expansion of its upstream gas assets.

Asked if any of this information gave PetroSA pause, it said: “Mazars, the transaction advisor, is conducting a due diligence [on] all aspects of the transaction and at this assessment phase there are no substantive reasons for not proceeding with the transaction.”

Mazars’ director of corporate finance, Rishi Juta, said his team was appointed after Equator had already been selected as the preferred bidder for RFP 0004 but declined to discuss their role further, citing client confidentiality.

The problem, as we pointed out to PetroSA and Mazars, was that Equator was being awarded contracts far beyond what they actually bid for.

Scope creep

The tender that Equator had won was for “the provision of funding” only, which meant that the bidders had to show their financial credentials but were not required to have any technical expertise.

The “gas and infrastructure financing and reinstatement agreement” that Equator signed on 11 December 2023 was very different.

Equator would now be in charge of refurbishing PetroSA’s gas infrastructure: the deep-sea FA platform, the infrastructure and pipelines that bring gas onshore, the gas portion of PetroSA’s gas-to-liquids refinery, and any infrastructure required for the plant to handle ammonia and LNG.

The contracts that PetroSA signed with Lawrence Mulaudzi make Equator Holdings the lynchpin in the government’s multibillion-rand gamble on gas. (Photo: Supplied)

PetroSA’s acting chief operations officer, Sesakho Magadla, alluded to this in the 11 December press conference: “In Mossel Bay, you have two plants: you have the gas plant and you have the liquids plant. Gazprom is on the liquids [plant],” she told journalists.

“We have tail gas that is currently sitting offshore, that is outside the scope of the Gazprom [deal], that scope with regards to the infrastructure that we must reinstate – which is the FA platform… the pipeline… plus the gas part of the refinery – … because the winning bid on that one is a local entity, that process is still under way.”

She added: “[W]e are in the process again of embarking a feasibility study with a partner on the gas infrastructure, which is… Equator Holdings.”

AmaBhungane has seen a draft version of the contract which – if unchanged – shows that Mulaudzi’s company will not only conduct the feasibility studies and provide the funding but will be in charge of “all the design, engineering, procurement, construction, fitting, installation, testing activities, commissioning works and services”.

As a condition in the draft agreement, PetroSA added that Equator would have six months to provide “evidence that it possesses the necessary technical capability” to undertake the projects it had already been awarded.

We invited PetroSA to explain the logic of selecting Equator for a highly technical project without any indication that it had the skills and experience.

It initially told us: “The evaluation team that assessed the bids found Equator Holdings to be competent as outlined by the evaluation criteria,” then added in a subsequent response:

“The criteria published with RFP 0004 was used to identify the partner. There is an agreement signed between the parties and Conditions Precedent (CPs) which must be fulfilled in accordance with the contract.”

In his two-page letter, Mulaudzi told us: “We emphasise that there are no grounds that would disqualify Equator Holdings… We are also aware that there are interested parties that may have desired a different outcome… This does not come as a surprise, as we are mindful that we operate in a highly competitive environment, which may tempt losers to puke ‘sour grapes’.”

Russian intervention

AmaBhungane’s research suggests that Mulaudzi has already started shopping for a technical partner. In October, he turned up at the office of South Africa’s honorary consul in Yekaterinburg, Russia, presenting himself as the executive director of EquaTheza.

A photograph of Mulaudzi’s visit to Russia in October was published on the honorary consul’s website with the caption: ‘Meeting with the executive director of EquaTheza Oil and Gas Exploration’. The post has since been deleted but the photo can still be found in the website’s source code. (Photo: Supplied)A photograph of Mulaudzi’s visit to Russia in October was published on the honorary consul’s website with the caption: ‘Meeting with the executive director of EquaTheza Oil and Gas Exploration’. The post has since been deleted but the photo can still be found in the website’s source code. (Photo: Supplied)

Hendricks told us that Mulaudzi was not in Russia on EquaTheza business but that his Russian partner had facilitated a meeting with Uralhimmash, a subsidiary of Russia’s sanctioned Gazprombank that specialises in gas infrastructure and equipment.

Russia’s state-owned entities have long been interested in PetroSA’s offshore development: in 2017, Rosgeo offered to spend $400-million (then R5-billion) to explore and develop blocks 9 and 11a; when the deal collapsed, some of Rosgeo’s technical experts formed Theza.

When Theza initially bid for RFP 0003, it proposed using Uralhimmash as its technical partner, with funding from Russia’s Exim Bank. But it had parted ways with both over concerns about sanctions.

“We have no Russian involvement, no Russian funding,” Hendricks insisted.

We asked if Uralhimmash had agreed to act as Equator’s technical partner. Equator would only say that it had engaged various strategic partners, including beyond South Africa’s borders: “This is meant to ensure that this project is executed efficiently, effectively, with the necessary capacity and required resources.”

PetroSA was equally coy: “Equator is having various discussions with a multitude of stakeholders as part of ensuring the successful execution of the transaction. As PetroSA, we are not at liberty to discuss in detail the stakeholder engagement proceedings of any of our strategic partners.”

Money woes

There is also the question of funding.

The original tender – to fund offshore gas exploration – required up to R21.6-billion. It is unclear how much Equator needs to fund the additional gas infrastructure projects it has been awarded.

But if the draft agreement is accurate, Equator is yet to secure any firm commitments. It shows that Equator has until March to show that it can raise money to refurbish the FA platform, the most urgent project on PetroSA’s list, and until June to show it has secured the rest of the funding.

Any money Equator lends to the project can be recouped with interest when the projects enter production, but this does not include the feasibility studies which Equator has agreed to pay for.

However, Mulaudzi’s own finances are famously chaotic, making it less likely that Equator will be able to raise funds from credible financial institutions.

Aside from having his Bentley and his Audi repossessed, it has also been reported that Mulaudzi is fighting off an application to seize his Camps Bay home after he was evicted from his Johannesburg offices for failing to pay rent, and then twice failed to stick to the repayment plans negotiated with his landlord.

In the past, the PIC had been willing to loan Mulaudzi’s companies R3.2-billion, but a spokesperson told us that this time it “has not considered funding Equator Holdings or any of its affiliates”.

When Mulaudzi approached the IDC for a letter of intent back in February 2023, it was on the understanding that Equator would partner with a little-known US-based company called Globus Energy Group.

Markam Naidoo, who is Globus’ local representative and also a director of Equator, told us that Globus had agreed to provide “funding support” to Equator and PetroSA but declined to provide specifics:

“So ultimately the funding would be a blend. We have relationships between the Middle East and the US. Ultimately our funding would most likely, for this type of project, come from the US – that’s where we are headquartered,” he told us.

We asked PetroSA if Equator had been able to secure finance, or even an indicative term sheet from the credible financial institution, which Equator was supposed to have to even get a foot in the door.

But PetroSA demurred: “The agreement between Equator Holdings and PetroSA enjoys the protection of an NDA [non-disclosure agreement] between the parties. Similar transactions have terms and conditions which each party needs to fulfil its obligations. It is of importance that the parties are afforded their rights to fulfil these obligations.” DM

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!