Warning: This story contains details of violence, including sexual violence, which some readers may find disturbing. The name of one of the participants – Ravi – has been changed to protect his identity.

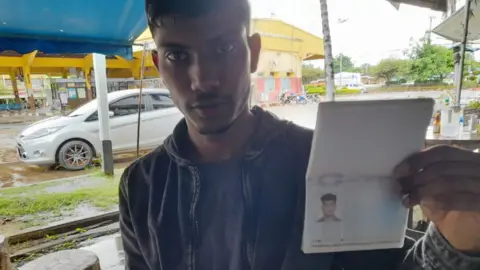

Ravi travelled to Thailand dreaming of a better life for him and his new wife.

Instead, the 24-year-old Sri Lankan found himself trapped in the Myanmar jungle, being tortured for refusing to help trick lonely, rich men out of thousands in so-called romance scams.

“They stripped off my clothes, made me sit on a chair and gave my leg electric shocks. I thought it was the end of my life.

“I spent 16 days in a cell for not obeying them,” he continued. “They only gave me water mixed with cigarette butts and ash to drink.”

But that was not the worst of it, he says. Five or six days in, two girls were brought in and gang raped in front of him.

“When I witnessed it, I feared, ‘What will these people do to me?’ It was then that I doubted they would let me live,” Ravi said.

Ravi said he was left so badly injured it felt as if one side of his body was paralysed

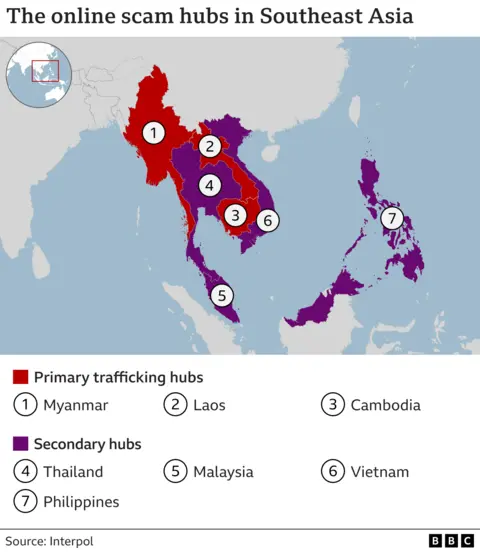

In August 2023, the UN estimated that more than 120,000 people, most of them men from Asia, had been forced to work in scam centres in Myanmar like the one Ravi found himself in.

The centres are fed by a steady stream of aspiring migrant workers from all over the world. The Sri Lankan authorities say they know of at least 56 of its citizens alone who are trapped in four different locations in Myanmar, although the Sri Lankan ambassador to Myanmar, Janaka Bandara, told the BBC that eight of them had recently been rescued with the help of the Myanmar authorities.

Ravi was one of those aspiring migrants, tempted by the promise of a job in data entry with a basic salary of 370,000 rupees ($1,200).

The computer specialist jumped at the chance – it was money he couldn’t dream of in Sri Lanka, which has been hit by an economic crisis.

And so, he took out a loan of 250,000 rupees ($815) to pay the recruiter.

Ravi arrived in Bangkok in early 2023, but was immediately sent to Mae Sot, a city in western Thailand.

“We were taken to a hotel, but soon handed over to two gunmen. They took us to Myanmar crossing a river,” Ravi explained.

The group ended up in Myawaddy – a town at the centre of recent fighting between the military regime which seized power three years ago, and allied anti-coup forces.

From there, they found themselves in a camp run by Chinese-speaking gangmasters, surrounded by tall walls and barbed wires, with armed guards protecting the entrance around the clock.

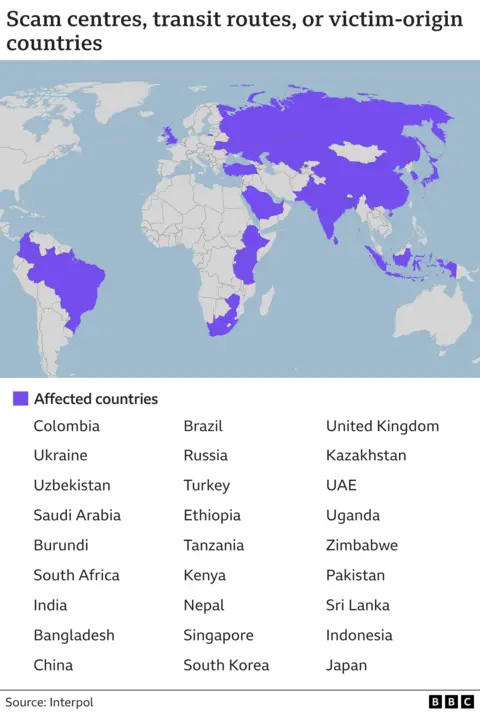

“We were terrified. About 40 young men and women, including Sri Lankans, individuals from Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and African countries, were forcibly detained in the camp,” he said.

While scam centres have popped up across South East Asia, they have been particularly prevalent in Myanmar, where they have generated billions of dollars for both Chinese underworld crime syndicates, and the various armed groups operating in border towns.

In this particular scam centre, the focus was so-called romance scams. The cost of such scams to victims is hard to establish, but the FBI found in its 2023 Internet Crime Report that there had been more than 17,000 complaints of confidence or romance scams in the US, with losses totalling $652m.

According to Ravi, he and the others were forced to work up to 22 hours a day – getting only one day off each month – and told to target wealthy men, particularly in Western countries, by building romantic relationships using stolen phone numbers, social media and messaging platforms.

They contacted the victims directly, typically making them believe the first message – often just a simple “hi” – was sent by mistake.

Some people ignored the messages, Ravi says, but lonely people or those looking for sex often took the bait.

When they did, a group of young women at the camp were forced to take explicit pictures to further entice the target.

After exchanging hundreds of messages in just a few days, the scammers would gain the trust of these men and persuade them to invest large sums of money in fake online trading platforms.

Fake apps then display false investment and profit information.

“If a person transfers $100,000, we return $50,000 to them, saying it is their profit. This gives the impression that they now have $150,000, but in reality, they only get back half of their initial $100,000, leaving the other half to us,” Ravi explained.

When the scammers have taken as much as they can from the victims, the messaging accounts and social media profiles disappear.

Disobey, and you faced – as Ravi had – beatings and torture.

But there are ways out: you can pay.

One man who did exactly that was Neel Vijay, a 21-year-old from Maharashtra in western India, who was trafficked to Myanmar along with five other Indian men and two Filipino women in August 2022.

He told the BBC that a childhood friend of his mother had promised him a call centre job in Bangkok, and had charged them an agent’s fee of 150,000 Indian rupees ($1,800).

“There were several companies run by Chinese-speaking people. All of them were scammers. We were sold to those companies,” Neel said.

“When we reached that place, I lost hope. If my mother hadn’t given them the ransom money, I would have been tortured like others.”

Neel made it back to India in less than two weeks with the help of Thai authorities

Neel made it back to India in less than two weeks with the help of Thai authorities

Neel’s family paid the gang 600,000 Indian rupees ($7,190) to release him after he refused to be involved in the scam, but not before he had witnessed the brutal punishment meted out to people who either didn’t meet the targets or couldn’t afford to pay the ransom.

After his release, the Thai authorities helped him get back to India, where his family has taken legal action against the local recruiters.

Ravi was also passed between gangs during the six months he was trapped in Myanmar.

He ended up in the cell after a confrontation with the team leader led to a fight.

“I told them that I couldn’t scam these people. Even though I had no money, I didn’t feel like stealing someone else’s hard-earned money. The thought alone caused me great mental anguish,” Ravi said.

Finally, the “Chinese boss” came to see Ravi and offered him “one last chance” to work again – a new opportunity due to his expertise in computer software.

“I had no choice; half my body was paralysed by then,” he added.

Neel, an Indian victim, was rescued by Thai authorities and crossed the river to safety

Neel, an Indian victim, was rescued by Thai authorities and crossed the river to safety

For a further four months, Ravi managed Facebook accounts set up using a VPN, artificial intelligence apps, and 3D video cameras.

Meanwhile, Ravi begged to be allowed to go to Sri Lanka to visit his ill mother.

The gang leader agreed to let him go if Ravi paid a ransom of 600,000 rupees ($2,000) and an additional 200,000 rupees ($650) for crossing the river and entering Thailand.

His parents borrowed money – putting their house up as collateral – and transferred it to him, and Ravi was taken back to Mae Sot.

When he was fined 20,000 Thai baht ($550) at the airport for not having a visa, Ravi’s parents had to take out a further loan.

“When I arrived in Sri Lanka, I had a debt of 1,850,000 rupees ($6,100),” he said.

He may be back home now, yet Ravi barely sees his new bride.

“I work day and night in a garage to pay off this debt. We have pawned both of our wedding rings to pay the interest,” he said bitterly.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!