In the footsteps of the Damara, San, Ovahimba and Ovaherero, Namibia’s tourism landscape offers an opportunity to experience the country’s pre-colonial times. Namibia is mostly known for having the world’s oldest dunes that meet the cold Atlantic Ocean, coupled with its contradictory vastness and the beauty of its heritage.

Over 200 kilometres north-west of Windhoek lies the town of Omaruru, founded by the Zeraua family in 1863.

Tour guide of 26 years Gotfriet Ekandjo says Omaruru is where some Ovaherero gather around the holy fire to pray for matters like the country’s prolonged drought.

When the war between the Germans and Hereros started in 1904, Omaruru was attacked and surrounded by Herero warriors. The town is home to a cemetery where graves of both Ovaherero and Germans are.

The town also houses the Franke Tower, which was built in 1907 to commemorate the victory of the Germans over the Ovaherero. A drive to the Omandumba San Living Museum at !Oe≠gans in the Dâures constituency take tourists back in time. The San community at the living museum showcase how they make fire using sticks, grass and determination.

Xao Kgau, the head of the community, says families are rotated at the museum every three months.

They live at Tsumkwe in north-eastern Namibia, which has one of the biggest San communities in the country.

“We come here to stay for three months and show the traditional lives, how the elders lived in former times. When we are done, we go back, then other families come,” Kgau says.

These museums display the forgotten history of these indigenous communities, while international organisations have called on the government to treat marginalised communities as equals. Kgau touts the leaf of the Moringa tree and the juice of the aloe plant for bringing them the type of medicines that the modern world cannot, while the marginalised San community, who were original custodians of Namibia, showcase their hunter gathering skills. An hour’s drive deeper into the Erongo region will lead you to the village of Okombahe, where many years ago the San community made rock paintings of themselves and their livestock.

In an effort to uplift their village, the Damara community at Okombahe started a sustainable conservation and small-scale mining project in the Erongo Mountains. Rock painting and small-scale mining are part of Namibia’s heritage and tourism route.

The route of the San people in the Erongo region is marked with rock paintings and drawings, like the famous ‘The While Lady’, which is estimated to be 5 000 years old.

The heritage demands a 70-kilometre round-trip hike through the mountains.

Once victorious at the hike, tour guide Chrisley Awaseb explains how the painting was found during colonial times.

Abbel Hendrik Breuil found the painting and decided to name it based on the white colour of one of the paintings. Since then, questions around the painting’s name have not subsided.

The heritage route takes tourists deeper to the Damara community from the Khorixas Mountains standing tall as they stomp their feet on the ground to the rhythm of traditional hymns filling the air.

The museum mimics old-time villages, designed in a circular format with an open middle section for dancing activities, and sections for blacksmiths, traditional medicines, a women’s workshop for jewellery making, a corner for traditional beer and a cooking area.

Damara goabs (kings) used to have more than two wives and would play a game called //hu¯s to settle any disputes.

Living museums ensure these ancient cultures do not die and that future generations know where they come from.

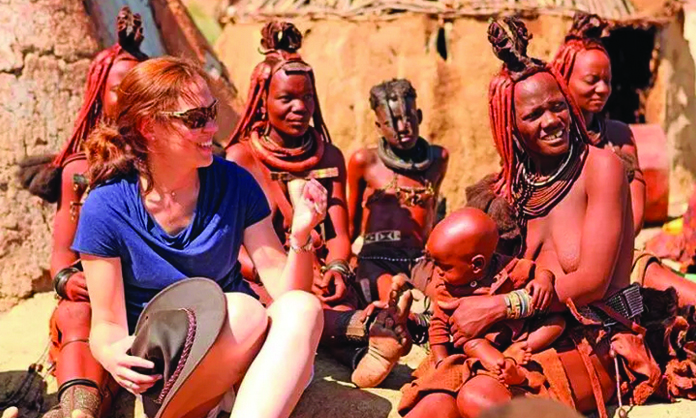

Namibia’s marginalised communities are on full display on this route, as the Ovahimba community allows tourists to step into their world at the Otjikandero Ovahimba Village.

The popular tourist attraction 20km from Kamanjab sees Ovahimba girls and women between the ages of 16 and 50 gathered in a semicircle to explain their practices, including that of child marriage. This is a sensitive topic in the country which has left many in the community feeling judged and misunderstood. They are adamant that child marriage is part of Himba culture, something which not everyone understands.

“From two years onwards the elders can arrange a marriage,” Ekandjo explains. He confirms that a 12-year-old girl’s union was arranged. She has to wear the veil until the village knows her well enough, he says.

Vipuakuje Muharukua, who is from the Ovahimba community, says since child marriage has declined, he has seen their children on the streets. This is due to the loss of their ‘safety net’ practice, he says.

“You have to realise two things about the Himba people: We do not have street kids. Yes, lately because there’s no more child marriage. The practice is not rife any longer.

“Secondly, the Himba people do not have children out of wedlock. Every child in the Ovahimba community had a father, and that is owing to child marriage,” he says.

Muharukua says a young or unborn girl is promised to a man and married at the age of one or two.

The marriage needs to take place at a very young age, he says.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!