The main unstated aim of the former liberation movements of southern Africa – an informal club of seven movements/parties that brought freedom to their countries – has always been to help each other stay in power.

Until recently, they had been doing a pretty good job of it as all had remained in power since independence.

But things now look gloomier.

In May, the African National Congress (ANC) lost its simple majority in South Africa’s legislative elections and was forced to form a Government of National Unity with several other parties.

In October, the Botswana Democratic Party (BDP), which had been in office since independence from Britain in 1966, was unexpectedly trounced in general elections.

It fell from 38 seats to four, and came only fourth in parliamentary seat numbers, conceding power to the Umbrella for Democratic Change.

After Mozambique’s presidential and parliamentary elections on 9 October, the national electoral authority declared an overwhelming victory for the ruling Mozambique Liberation Front (Frelimo) and its presidential candidate, Daniel Chapo.

But the opposition said the results were rigged, declaring Venâncio Mondlane the winner.

Some independent observers, including the Episcopal Conference of Mozambique and the European Union, also reported evidence of rigging.

Mondlane unleashed a cascade of protests that security forces violently dispersed, shooting more than 30 people in the aftermath of the election.

The outcome of this unprecedented wave of demonstrations remains uncertain.

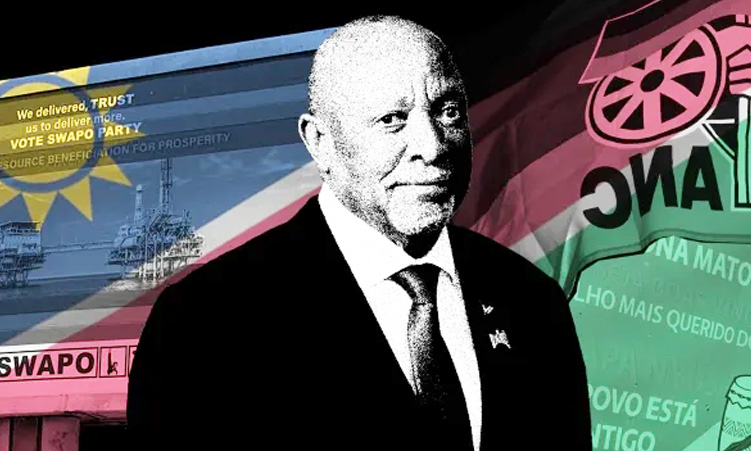

Now general elections are looming in Namibia on 27 November, and some analysts predict that the ruling South West Africa People’s Organisation, now the Swapo Party of Namibia (Swapo), in power since independence from South Africa in 1990, could go the way of the ANC or BDP – or, less pleasingly, Frelimo.

Henning Melber this week wrote on The Conversation: “Swapo might face defeat for the first time since independence in 1990.”

Melber is a Swapo member and an extraordinary professor of political science at the University of Pretoria.

He notes that in the 2019 elections, the late president Hage Geingob was re-elected with the worst result ever for Swapo, only 56% – down from 87% in 2014.

His erstwhile Swapo comrade Panduleni Itula, running for president as an independent candidate, amassed an impressive 30% of the vote.

Swapo’s downward trend “was confirmed by a dramatic decline in support in the 2020 regional and local elections”.

Now, he says: “Swapo faces a new quality of opposition. For the first time a clear victory for Swapo seems less certain.”

Melber said Swapo’s presidential candidate for this month’s polls, Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah, faced strong competition from Itula and his new Independent Patriots for Change, which he said made inroads in its first contest – the 2020 regional and local government elections.

Melber identifies a general obstacle faced by many African opposition parties trying to dislodge a stubborn incumbent.

That is the failure to unify around a single presidential candidate or party because of “factionalism, internal conflicts and a perennial struggle for power”.

This might just save Swapo, but Melber sees the possibility of Swapo and Nandi-Ndaitwah falling below 50% of the vote and being defeated.

Or being forced into a coalition with the opposition.

Or – “in an unlikely but possible scenario” – some other candidate, probably Itula, could win the presidential election while Swapo controls the National Assembly, creating two centres of power.

Graham Hopwood, the executive director of the Institute for Public Policy Research in Windhoek, also believes Swapo could have “its poorest electoral performance since independence”.

“There are indications that much of the urban youth vote is frustrated with the ruling party, and their participation in this election could have a strong influence on the outcome,” he says.

However, Hopwood thinks none of the opposition parties are making a strong enough pitch to this disaffected youth vote, and much of Itula’s support in 2019 was just a protest vote.

“But he is no longer the new kid on the block, and his appeal may have dimmed in the intervening time.”

Hopwood nonetheless thinks high youth unemployment, nearly 50% in 2018, will be the key factor driving young people, especially the urban youth, away from Swapo.

He thinks Covid-19 probably increased unemployment.

He says the government has just published the main census results without any employment statistics, “provoking claims that they . . . censored the report”.

Disenchantment with corruption, particularly the Fishrot scandal that rocked the party over the past few years, is also a factor.

Hopwood says: “There is no quick fix that any government can take on the joblessness situation. Namibia’s oil and gas discoveries won’t move into production phases until 2029 at the earliest, and even there will be limited job creation. The same goes for Namibia’s green hydrogen ambitions.”

POLITICS OF EXCLUSIVITY

Nevertheless, much voter disenchantment stems from poverty and unemployment levels in Namibia and regionwide.

This is aggravated by “a politics of exclusivity [that] sees only those connected to political and economic elites benefiting,” says Piers Pigou, the head of the Southern Africa programme at the Institute for Security Studies.

For the born-frees, “clearly the allure of Swapo as a former liberation movement is fading”, Hopwood says.

“Young people have no memory and little knowledge of the pre-1990 era. They are likely to judge Swapo on its job creation and service delivery record, which has been mixed at best.”

The same causes could be identified for the declining support for incumbent former liberation movements in South Africa, Botswana and Mozambique, and elsewhere.

CONTAGION

Arguably too, there has been contagion.

Just as former liberation movements support each other to stay in power, so opposition parties appear to be drawing inspiration and courage from the successes of their kindred spirits across the region.

Identifying as a former liberation movement is probably becoming a liability, not an asset.

Membership of the club may be on the decline even if some members – like Frelimo, Zanu-PF, Angola’s MPLA and perhaps Tanzania’s CCM – continue to violently resist the trend.

Melber says Swapo could have a future even if it loses its outright majority.

“Swapo could get beyond the nostalgic liberation struggle mindset and reinvent itself as a modern political party. This could – as happened in South Africa – pave the way to enter coalition politics in the best interest of the people.”

Or if necessary, as the BDP so inspirationally did, it could simply concede defeat and exit office with no fuss. – Daily Maverick

– Peter Fabricius is a consultant at the Institute for Security Studies (ISS)

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!