Staff say they can’t authorize any transactions. Clients can’t open accounts. But the newcomer remains in suspended animation at the center of a political tussle.

Not much happens in Bulembu these days. The little company town grew around an asbestos mine that began operations in 1939. By the 1960s, Havelock Mine was one of the world’s biggest producers of the lethal mineral, but in 2001 the mine abruptly shuttered amid a plummeting demand for asbestos. Most of Bulembu’s inhabitants left in search of work.

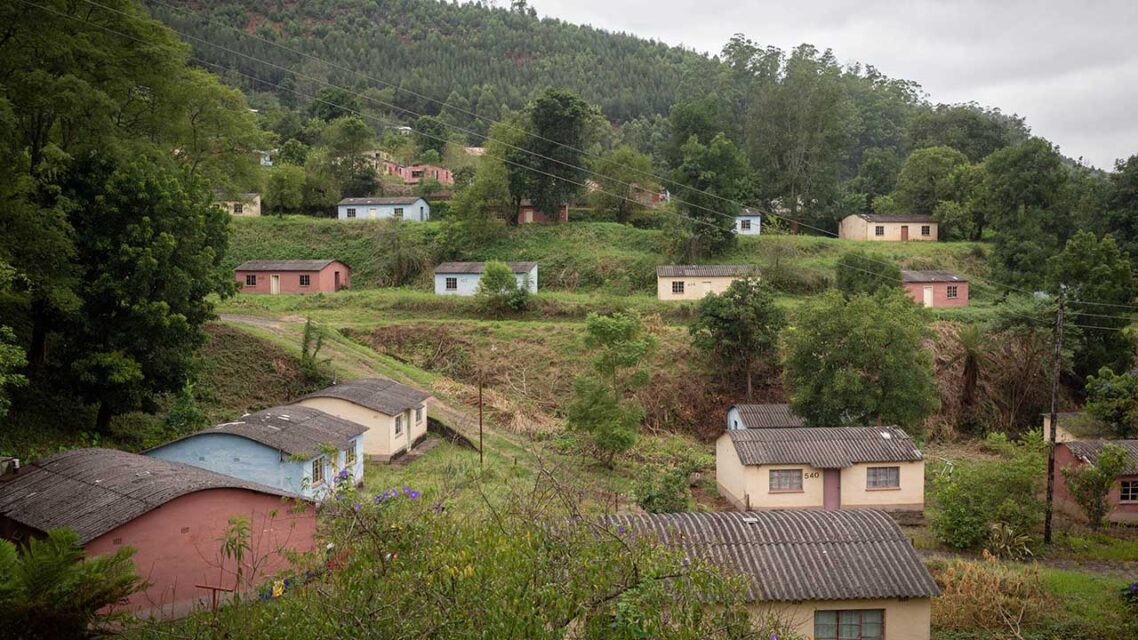

Bulembu sits in a green valley surrounded by timber plantations in a remote part of Eswatini, a tiny southern African kingdom of 1.2 million bordered by South Africa and Mozambique. Known as Swaziland until its king unilaterally changed its name in 2018, the country is ruled by the last absolute monarchy in Africa. Given the lack of businesses, the town in 2019 was a strange place for a bank to set up shop, in a simple one-story building with white walls and a green roof — the colors of Farmers Bank’s corporate logo. Inside, it is like any other bank: shiny imitation marble floors, a teller counter and a neat row of chairs, though they are still wrapped in plastic. The Farmers Bank employees in Bulembu and at its other branch in Manzini — Eswatini’s commercial center — arrive for work each weekday morning, but there is little more to do than water the potted plants and wait. The staff say they cannot authorize any transactions. Clients cannot yet open accounts, and the staff cannot issue loans.

Farmers Bank was supposed to rival the big, established high-street banks operating in Eswatini — mostly South African banks — and launch over 200 ATMs in its first 12 to 18 months. But it’s essentially a bank in name only. For the past few years it has been engaged in a tug-of-war with the regulator, the Central Bank of Eswatini, over its banking license.

Leaked documents capture multiple contradictions that played out in the Farmers Bank saga between a central bank designed to be independent and ensure financial probity and an opaque and unaccountable monarchy. They tell the story of how the CBE was alarmed by a litany of discrepancies in Farmers Bank’s application for a banking license, and in trying to put the brakes on the process, the CBE ran up against the political interests of King Mswati III and his associates.

As part of the project called Swazi Secrets, this investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists reveals that Eswatini’s finance minister, Neal Rijkenberg, was unusually involved with the bank, placing him in a potentially serious conflict of interest. In fact, the bank’s very location in Bulembu — which sits on land owned by a Christian nonprofit organization called Bulembu Ministries that Rijkenberg founded and once chaired — is one of several indications that he is linked to the bank and its Canadian owners.

The documents comprise more than 890,000 internal records from the Eswatini Financial Intelligence Unit obtained by Distributed Denial of Secrets, a nonprofit devoted to publishing and archiving leaks, which shared them with ICIJ. ICIJ coordinated a team of 38 journalists from 11 countries to investigate illicit or suspicious financial flows in southern Africa and beyond.

The EFIU, an independent statutory body intended to “provide financial intelligence that safeguards the local and international financial system” from money laundering, terrorism financing and other illicit activity, operates in Eswatini’s capital Mbabane and formed when the kingdom passed the Money Laundering and Financing of Terrorism Act in 2011, which was designed “to criminalise money laundering and suppress the financing of terrorism.”

The EFIU obtains so-called suspicious transaction reports, or STRs, from banks and financial institutions and uses that information to provide financial intelligence to Swazi and international authorities. Its task is to identify, monitor and investigate suspicious financial transactions, but its investigative powers are tightly circumscribed, and in most cases it cannot subpoena witnesses, conduct interviews or gather intelligence. Although the banks and EFIU flag countless transactions as “suspicious,” this does not show proof of wrongdoing but reflects suspicion of potential illicit activity.

The EFIU has regularly identified potentially serious crimes involving millions of dollars of possible illicit transactions. The subsequent investigations by the police and other authorities, though, have tended to stall and rarely ended up in successful prosecutions. As Eswatini’s National Risk Assessment — a high-level government review of the country’s exposure to money laundering — noted: “Even though safeguards exist in law, politicians may interfere with [financial crime] investigations for example. … Although [financial crime] investigators are well protected in terms of the legal framework, in practice they are not well protected against these political pressures.”

In Eswatini, independent institutions such as the EFIU and the central bank co-exist in an uneasy relationship with the monarchy. “At the most basic level if you’re not going to have a financial intelligence unit you are going to be gray-listed by FATF [the Financial Action Task Force, the global anti-money laundering watchdog],” says Holden. “And that has all sorts of knock-on effects in terms of … whether you can get investment into your location.” Holden says there are pressures compelling countries to establish institutions like the EFIU and ensure a degree of central bank independence, even in an absolute monarchy.

‘A royal command,’ a litany of errors

Back in August 2009, real estate developer John Asfar was facing financial trouble as the owner of Travellers Inn, one of the largest hotel chains in British Columbia, Canada. Travellers Inn was on the verge of bankruptcy, with creditors demanding $54.3 million. Asfar told local media that he had a plan to sell off some of his properties to settle with creditors and would offer them “100 cents on the dollar.” He said he had had enough of Canada’s government and tax system and would be moving to Africa to help the poor and orphans. The following month, Travellers Inn filed for bankruptcy.

Ten years after the demise of Travellers Inn, Asfar was involved in setting up a branch of Farmers Bank in quiet Bulembu on the border with South Africa, where there is no public transportation, no gas station and the nearest town is accessible only by driving 11 miles on a rough dirt road.

The thought of a new bank opening in Bulembu provoked the curiosity of local media. One journalist who traveled to the town asked in an article: “what is a bank doing in the sleepy town with virtually no activity to attract banking business?”

By then, Bulembu was already closely associated with Rijkenberg, who was at the time a prominent businessman in the forestry industry. In 2004, the town had been effectively taken over by the Bulembu Development Corp., for which Rijkenberg was a director and shareholder. When the corporation’s plans to rehabilitate the town and attract business fell through, the shares in the holding company that owned the property were transferred to Bulembu Ministries — the Christian nonprofit founded by Rijkenberg. With the backing of Canadian donors, Bulembu Ministries aimed to breathe new life into the town by setting up social enterprises and an orphanage.

A born-again Christian and ardent believer in the free market, Rijkenberg is also the chairperson of Silulu Royal Holdings, a private company established by the king and registered to the monarch’s office.

After the king transferred about 37,000 acres he held in “trust” for the benefit of the kingdom’s people to Silulu, ordinary citizens evicted from the land accused him of “land grabbing.” Ostensibly, the transfer was to widen access to small-scale Swazi (as the people of Eswatini are known) farmers, but instead the land has been leased to commercial farming operations, with the profits going to the royal company.

The origin of Farmers Bank, however, starts before Rijkenberg was appointed finance minister in late 2018, and there were signs that the bank was beginning the process to enter the Eswatini market in late 2016 or early 2017. This finding is from a 2022 report by the New York-based financial and risk advisory firm Kroll, which was commissioned by the CBE to review Farmers Bank’s application for a banking license. The confidential report was obtained by ICIJ’s South African partner, OpenSecrets.

According to the Kroll report, an unnamed CBE official said in an internal email that he received a request “in late 2016 or early 2017” from someone named Sikelela Dlamini to meet with “acquaintances of one of the Princes” about the banking license application process. The official believed — though could not confirm — that the request concerned Farmers Bank, the report says.

On July 14, 2017, Majozi Sithole, the governor of the CBE, sat down for a meeting with then-Minister of Finance Martin Dlamini, the minister of agriculture and unidentified businesspeople who wanted to set up a bank in the kingdom. There were early indications of high-level interest in the venture when Sithole wrote in an internal email that he was given a “royal command” from the king to attend the meeting, the Kroll report notes.

As the last remaining absolute monarch in Africa, King Mswati III holds veto power over all branches of government and is constitutionally immune from prosecution. The royal family has interests in various facets of Eswatini’s economy and grabs property, shares and other assets seemingly at will. Critics and rights organizations allege that nepotistic appointments of royal family members and associates to board positions at large private firms and government-owned entities is the norm.

“When we talk of the Swazi economy we can say the king himself is the economy, because Swaziland is emblematic of a country where the entire economy is actually captured by royal interests,” said one Swazi human rights activist who asked not be named for fear of retribution.

Those in the king’s favor operate with impunity, say rights groups like Amnesty International. King Mswati III and his large family — whose size is a secret but said to be 11 wives and more than 30 children — have a reputation for flaunting their lavish lifestyles, which detractors of the monarchy say shows a callous disregard for the suffering of his subjects, who mostly live in impoverished rural areas and struggle to find work.

On the day of the meeting Sithole attended at the king’s instruction, Farmers Bank submitted an application for a banking license. Over 500 pages long, it contained a litany of errors, discrepancies and what looked to be questionable audited financial statements, according to the Kroll report. ICIJ’s investigation found that names of proposed executives were misspelled, their roles were mixed up and the statements incomplete.

Farmers Bank also said in its application that it was preparing to move into a glitzy four-story office building in George, South Africa, which it said would be called the Worldwide Corporate Center and would house “one of the most technologically advanced & largest Boardrooms in Africa.”

But that building, under construction at the time, was owned by South African property company Dynarc, via a related company. Dynarc’s financial director, Vanessa Blom, told ICIJ that Equity Check Capital, a company that listed John Asfar’s brother as its sole director, was going to lease a large portion of the building. Blom says Dynarc mostly dealt with John Asfar and that neither Equity Check nor Farmers Bank ended up moving into the building. Dynarc obtained a judgment against Equity Check for breach of contract, says Blom, but her company has not been able to contact the Asfars.

In over 100 pages, the Kroll report corroborates the CBE’s concerns about Farmers Bank’s application for a commercial banking license that the central bank initially rejected in late 2017. But as the report shows, the CBE came under political pressure to walk back its decision.

A finance minister’s mysterious connection

In May 2018, according to the Kroll report, then-finance minister Dlamini informed the CBE that the king had ordered an investigation into its licensing process and its “reluctance” to issue a license to Farmers Bank, despite the errors and inaccuracies of the application. ICIJ could not confirm if that investigation happened or, if it did, what the outcome was. But in September of that year, another “royal command” directed the central bank to grant a full commercial license to Farmers Bank, the report shows. The CBE complied, though the approval was subject to conditions, including that Farmers Bank submit additional disclosures about the source of its seed capital. The Kroll report also contends that throughout the application process, Farmers Bank was evasive about the background and role of John Asfar, who founded the bank with his brother Alexandre. The two are sons of Egyptian-born real estate developer Najib Asfar, who died in 2011.

The CBE had “concerns around the transparency of beneficial ownership and control of Farmers Bank and connected companies,” the report says. Those concerns “increased due to the involvement of J. Asfar.” John Asfar was a key player in the Farmers Bank matrix. He was a director of the bank and a director of the company that owned all of its shares, New Zealand-registered Worldwide Capital Corp. Ltd., as well as that company’s owner, Tetrillion Corp., which was registered in Canada. John Asfar was also a director in, and had control over, an Eswatini-based company, Pentillion, which would hold Farmers Bank’s reserves in silver bullion. Pentillion was “outside of the immediate Farmers Bank corporate structure,” but its “financial operations also appear to overlap with those of Farmers Bank” and it made monthly payments to the bank’s staff, the report says.

Yet Farmers Bank downplayed Asfar’s involvement in the bank and claimed that his role was merely to “set up the bank,” according to the Kroll report. “Such a statement suggests that his role does not extend to involvement in the ongoing operations of Farmers Bank once it had been incorporated,” the report reads. “However, in respect to Pentillion alone, J. Asfar is intricately involved in the operations of this company and also in the management of Farmers Bank’s most significant asset, the silver bullion.”

In a long letter to ICIJ, John Asfar didn’t respond to any of the specific questions ICIJ posed to him for this story but wrote that “For the record, 99.99% of each question/subject is a false narrative” and that the story ICIJ was planning, as he discerned it, was “financial terrorism.”

Alexandre Asfar did not respond to ICIJ’s requests for comment.

Farmers Bank maintained that Alexandre Asfar was the “controlling shareholder and beneficial owner” of the bank’s holding company, Tetrillion, but the CBE suspected John Asfar also had an ownership stake in the bank via the holding company. However, the CBE was unable to independently verify Tetrillion’s shareholding, notes the Kroll report.

John Asfar, however, was a director of the bank and was supposed to submit personal financial records and a CV that the central bank required to perform a so-called fit and proper assessment, which he refused to do, according to Kroll.

On Oct. 5, 2020, the CBE notified the bank of its decision to revoke its license “on the basis that Farmers Bank had failed to satisfactorily demonstrate the source of its seed capital and that it had failed to commence operations within the prescribed twelve-month period.”

Rijkenberg was appointed by the king to the finance ministry in 2018. “When I was appointed to be a member of parliament, I realized His Majesty might have a plan to put me somewhere,” he said in an interview with local media at the time.

Two days after its license was revoked, Farmers Bank notified Rijkenberg of its intention to appeal. According to media reports, when the appeal was lodged, Rijkenberg, who as finance minister would normally have heard the appeal, recused himself. He appointed the minister of commerce, industry and trade, Manqoba Khumalo, to adjudicate the matter. The Kroll report does not include Rijkenberg’s reason for the recusal, but Rijkenberg told ICIJ in an email that the Asfars rented a building in Bulembu “to use as a bank one day” and confirmed that he founded the organisation that runs the town and was on its board: “Due to there being a link to [Farmers Bank] before I became a Minister of Finance, I felt it best to recuse myself.”

The Kroll report, however, notes that the CBE informed both Farmers Bank and Rijkenberg on Jan. 17, 2020, of its intent to revoke the license. According to the report, “the turn of phrase and wording used in the notice to Minister of Finance Rijkenberg suggest that he was possibly given notice prior to Farmers Bank, and that he and the CBE had consulted each other in relation to the matter on previous occasions.”

“As Kroll was not provided with documentation in relation to consultations between Minister of Finance Rijkenberg and the CBE, we have not been able to confirm this point,” the report says.

In December 2020, Khumalo determined that Farmers Bank should retain its license and that there was “no compelling reason to doubt the source of funds.”

The CBE objected to the “procedural improprieties” used for the appeal, specifically that “the appeal was conducted in the absence of the regulations governing the process” — a claim backed up by the Kroll report. Beyond that, the report refutes Khumalo’s idea that there weren’t convincing reasons to doubt the origin of the capital, demonstrating in detail the inconsistencies and omissions in Farmers Bank’s explanation of the source of its money, in addition to the lack of transparency in the bank’s corporate structure.

Nevertheless, in January 2021, a month after Khumalo’s ruling, the CBE reluctantly reinstated Farmers Bank’s license, conditionally, giving the bank until January the following year to begin operating and insisting that it provide “financial statements of all individuals and companies directly or indirectly linked to the initial capital” and “three (3) months bank statement(s) from all bankers of FB’s main shareholder, Mr. Alexandre Asfar.” As that deadline approached, however, Farmers Bank requested a nine-month extension. The CBE gave it only two and cautioned that it had still not provided documents to substantiate the source of its initial capital.

In February 2022, Farmers Bank wrote to Rijkenberg seeking his intervention in the “impasse” with the CBE. It is unclear what, if anything, Rijkenberg did, but two weeks later the central bank changed its position and allowed an extension to September 2022. The Kroll report, which was completed during that time, could not find any rationale for the extension.

There are several records in the leaked documents linking Farmers Bank to the finance minister. A March 2019 import permit for Pentillion — the company that would hold the bank’s reserves in silver bullion — gave its address as Usutu Mill in Bhunya. The mill is owned by Montigny Investments Ltd., a forestry company Rijkenberg founded in 1997 and still has a stake in.

Bank statements reflect various payments involving Rijkenberg and the nonprofit he founded, Bulembu Ministries, and entities linked to Farmers Bank. The payments were relatively small but showed a link between the finance minister and those behind the bank. Bank statements from 2019 to 2021 show that both Worldwide Capital and Pentillion — two of the companies tied to the Asfars — made multiple payments of differing amounts to Bulembu Ministries. These were usually worth a few hundred dollars (several thousands of South African rands). Worldwide Capital bank statements reflect one payment to the company of $907 on March 29, 2021, labeled “Neal Rijkenberg.” Rijkenberg’s name also appeared on a Nov. 29, 2019, payment of $751 to Nhlonipho Dlamini, who while chairman of the board of directors at Farmers Bank was also being paid monthly on retainer by Montigny-owned Usutu Forest Products Ltd. as a “consultant.” It is unclear why Rijkenberg’s name appears on the statements and whether the money came from him.

Rijkenberg did not answer detailed follow-up questions about the payments and said that he could not respond to what he called “illegally obtained or leaked information as it would be a breach of the laws of Eswatini.”

It was not the first time Eswatini authorities came across payments involving Rijkenberg’s companies. In September 2017, South African commercial bank First National Bank sent the EFIU a suspicious activity report concerning its client, Usutu Forest Products, when it transferred funds to U.S.-Israeli cyber firm Verint, which was found by Amnesty International to have sold sensitive surveillance technology to the South Sudanese government “despite the high risk that the equipment could contribute to human rights violations.”

First National Bank’s report stated that the transaction was for the purchase of a PI2 system, “purportedly on behalf of the Royal Swaziland Police.” Verint’s PI2 system, known as the Grabber, is a highly sophisticated device able to intercept, decrypt and record mobile phone and satellite calls and messages without leaving a trace. Such a system, noted the report, “would generally be procured through the Government and not private entities” and was “not in line” with Usutu Forest’s business.

The transaction was referred to Eswatini’s Anti-Corruption Commission for investigation. In a May 2020 report, years after the Usutu transaction was first reported, the commission noted that the matter was still “under investigation” and that Usutu was thought to be a conduit for the Royal Eswatini Police Service to procure “investigative tools.”

Responding to written questions, First National Bank Eswatini said it could not comment, citing “regulatory and legal obligations” that prevented it from disclosing “confidential customer information.”

The EFIU, CBE and ACC issued a joint response to ICIJ’s requests for comment, saying that “Without confirming the veracity or otherwise of the information contained in your emails, kindly be informed that we cannot respond to questions on any information relating to confidential communications and operations other than to entities legally entitled to hold this information as that would amount to breach of the laws of Eswatini.”

‘Perplexing’ explanations

In 2019, First National Bank, where Farmers Bank had two accounts, decided that it did not have the appetite for the risks associated with Farmers Bank and terminated their relationship, citing “inconsistencies … pertaining to the information contained in the client’s KYC documents.” KYC refers to “know your client” — the obligatory steps required for a bank to verify a client. According to a note contained in the leaked EFIU records, First National Bank determined that Farmers Bank had “falsified” documents about its directors, which aroused suspicion that Farmers Bank was just a “shell bank” — in other words, a bank created for reasons other than its stated purpose and potentially to facilitate hidden financial maneuvers.

“If you control a bank, you control the reporting mechanism, so you can move all sorts of money in and not raise red flags with authorities,” observed Paul Holden, the financial expert. “But also if you’re registered as a bank you have all sorts of abilities to create esoteric financial instruments … which makes things easier to hide.”

Farmers Bank’s coyness about the identity of who owned and controlled it, and about the source of its funding, only fueled suspicion at the CBE. At first, when it applied for its license, the bank did not specify the origin of its funding, which the central bank inferred from the included financial statements would come from its ultimate parent company, Tetrillion. But the CBE wanted to know more. According to the Kroll report, the original source of that seed capital from Tetrillion was unclear, and three years of audited Tetrillion financial statements only further muddied the waters.

ICIJ reached out to Tetrillion for comment but did not hear back.

“Our review of the information in these financial statements has identified accounting treatments for certain assets which do not appear to follow accepted accounting principles, as well as notes to the statements which are illogical, contradictory, and unclear,” the Kroll report says.

“The integrity and reliability of Tetrillion’s financial statements appear to be questionable, which supports concerns raised by the CBE in its assessment report that the source of the Applicant’s seed capital had not been adequately evidenced or explained,” it concludes.

After inquiries by the CBE, Farmers Bank claimed its seed money was coming from the inheritance Alexandre Asfar received from the estate of his deceased father. According to the Kroll report, the bank then changed its story, saying there was no link between the seed capital and the inheritance, and that instead the money had come from the sale of properties in Canada — houses and apartment buildings — that Alexandre Asfar held through companies and a trust. The CBE found the about-face “perplexing,” the report says.

As it turned out, between August 2015 and November 2017, Alexandre Asfar had transferred about $9.8 million in 15 payments to an account of South African lawyers Wynand Naude Inc. — a conduit for the money to fund the bank — according to the Kroll report. But Farmers Bank was unable to adequately explain the source of five of these payments, three of which had “no established link” to the sale of a property, the report shows. Kroll also found there were missing wire confirmations, and although Farmers Bank repeatedly told the CBE that the properties sold to generate the seed capital were owned by Alexandre Asfar, it provided no documentation to show that he was the true owner.

In March 2020, having received information from the CBE, the Eswatini police reported the Asfars to Interpol on suspicion of having submitted fraudulent documents to the central bank. “They [the Asfars] presented copies of their passports, copy of bank statement, and other documents which are suspected to be fraudulent,” the police said in a formal request for Interpol’s assistance.

Interpol would not comment for this story as to whether there was any investigation and, if so, what came of it.

Meanwhile, years after Farmers Bank opened in Manzini, in a shopping arcade overlooking a busy junction, the staff still dutifully show up to work. There are no customers in the branch, only workers with seemingly nothing to do. Nonetheless, one employee told an ICIJ reporter who visited the branch that they hope to be up and running as a normal bank sometime this year.

Warren Thompson is a reporter with Finance Uncovered.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!