This scholarly book by author Henning Melber is based on a diverse and impressive body of literature. The fruit of much reflection on colonialism, the book is a testament to hope.

In the preface to the book, the author tells the reader that he intends journeying into “the heart of colonial Germany and its remnants today”.

Significantly, he also sees the journey as personal.

The idea of living in the wreckage of colonialism can constitute a productive place to think and act from. Invoking postcolonial theories and memory discourse, the task is not simply to deconstruct older narratives, but to fashion new ones, while acknowledging: “We cannot change the past, but we can change our blindness to the past”.

The author lays before the reader the main currents of thought – enlightenment, racism, colonialism and genocide – that gave rise to colonial mass violence.

What he calls, “the dark side of Enlightenment” in Western philosophical canon, with a Eurocentric civilising mission and the contested idea of “progress” as constitutive elements, the author posits: “The link between colonialism and genocide remains an integral part of European modernity and its legacy”.

German Colonial Brand

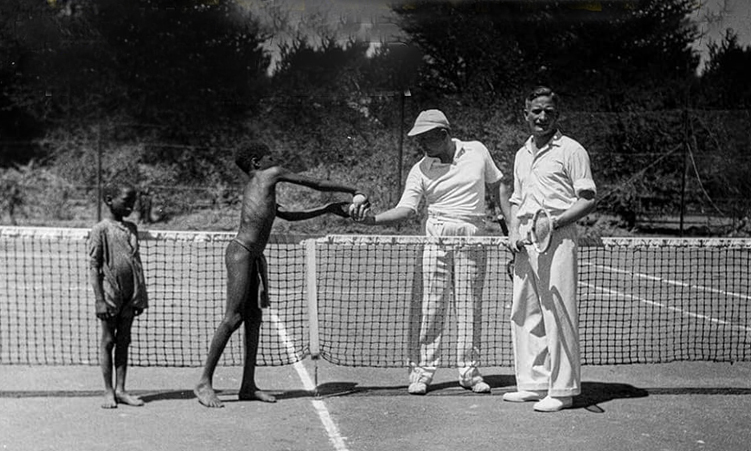

Chapter 3 offers a critical reading of ‘the German Colonial Brand’ in different contexts, replete with its “civilising agents”, the notion of terra nullius (“the land of no one”), the romantic notion of Heimat (imperial homeland), the politics of space and the expropriation of land.

Building on the previous chapter, Chapter 4 teases out the lineaments of ‘(Post-) Colonial (West) Germany’ as a precursor to what follows in the following two chapters. What informs the analysis is the argument that “memories of the colonial era and entanglements linger on in the present” and how these continue to impact German development policy.

The presence of the German-speaking minority in post-independent Namibia continues to imprint diplomacy, culture and intellectual life.

Since the 1990s, the advent of African, development, cultural and postcolonial studies, colonialism came into sharper relief.

The author points to two implications of this. First, it impacted Germany’s politics of memory, that since then took on the features of “screen memory”, a “covering memory” that occludes or ignores the past. Secondly, it also played its part in the construction of German identity.

The chapter concludes with a nuanced consideration of the ominous rise of ‘Reactionary Revisionism’ and its denialism of the Holocaust and other moral crimes committed in the colonies. The chapter culminates in a textual analysis of key parliamentary debates on colonialism in that country and poses the question if some form of ‘internal liberation’ is possible.

Germany and Namibia

For Namibian readers, Chapter 5 that deals with Germany and Namibia may well be the jewel in the crown. The underlying premise is that whereas it is possible to rule lives and bodies, it is not right, nor possible, to rule minds.

In any consideration that privileges justice and fairness – the supportive pillars of genuine reconciliation and reparations – there has to be room for non-European perspectives in the study of any colonial past.

In a masterful rendition, the author trawls over the twists and turns of the negotiation process between the two countries, the legal battles in the United States, land matters, legal doctrine, Namibian disagreements, alternative voices, and the most recent developments in Germany and Namibia in the aftermath of the largely flawed Joint Declaration of May 2021.

The author concludes by echoing the sentiments of the late Jewish historian Yosef Yerushalmi, who once asked: “Is it possible that the antonym of ‘forgetting’ is not ‘remembering’ but ‘justice’?

Challenging Colonial Asymmetries

The author contrasts the international respect that Germany earned in relation to the Holocaust through acts of restitution, while refusing to come to terms with moral crimes committed in that country’s former colonies.

The explanation for this paradox lies in the construct of “selective memory” – “cultural dementia” – that denotes “particular kinds of forgetting, misremembering and mistaking the past”. Unlike other forms of “selective memory”, “cultural dementia” is largely “irreversible”.

Amnesia does not mean the absence of colonialism in the public sphere. Rather it means “that the dominant discourse ignores existing counter-knowledge or applies some degree of immunisation against its revelations”. Such counter-knowledge is either expunged or fails to enter memory. “Hegemonic Knowledge” and power went (and continues to go) hand in hand in sustaining “colonial relations”.

Notwithstanding the difficulties associated with “learning from the past”, we need to do so. Local memory spaces can be translated into transnational memory spaces and this in turn could open up possibilities for a truly human encounter through mutual learning and sharing.

Thus, the “coloniality of power” can be reshaped by an alternative discourse and political practice.

German colonialism is the metallic counter on which Melber throws down his human coinage to test the claims of trueness by those who suffer from amnesia and those who continue to live in denialism.

‘The Long Shadow of German Colonialism Amnesia, Denialism and Revisionism’ deserves to be widely read and discussed in Germany, Namibia, and beyond.

– André du Pisani is professor emeritus of politics at the University of Namibia.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!