Thirty-four years after independence, Namibia’s former liberation movement seems poised to face its toughest challenge to remain in political control of the country’s central government.

But can anything new be expected?

The presidential and National Assembly elections of November 2019 illustrated wear and tear with the first major decline in voter support.

The results of the Regional and Local elections of 2020 reinforced the message that a heroic narrative of a patriotic history has reached its expiry date.

The born frees – and many among those who welcomed Independence – have experienced and reacted to new and sobering realities.

Civil Liberties, Democracy And Socio-Economic Realities

On 21 March 1990, a Constitution protecting civil liberties and human rights, the rule of law, and a plural multi-party democracy were reasons to celebrate.

However, those hoping for a better life for all under a government caring for all, instead of mainly for itself, were disappointed.

Controlled change has resulted in changed control.

While a new state administration recruited from a struggle generation moved into office, beneficiaries were mainly limited to an old and a new elite.

The composition of the haves has been modified since independence.

Its blend suggested majority rule and access to privileges for all.

A closer look shows this contrasted with the reproduction of the brutally stark class character of society.

Self-enrichment and clientelism for the benefit of some but at the expense of most continued.

Despite its relative wealth, Namibia remains one of the most unequal societies in the world.

Poverty, hunger, destitution, and marginalisation remain constitutive elements of an elite project.

Human dignity needs more than formal democratic rights.

It also needs necessary material improvement as an empowerment of individuals to fight for their rights.

A daily struggle for mere survival is not fertile ground for democratic participation.

It does not strengthen civil society advocating transparency and accountability by those who govern.

Alternatives Remain Wishful Thinking

One would have expected that the last election results would result in significant improvements for the ordinary people. This turned out to be wishful thinking.

The blame has been put on the continued rule of one party in central government so far. The verdict on its performance is pending.

Contenders promise to do better.

However, following the unfolding election campaign, there are reasons to be more sceptical.

The overall party political picture is rather sobering.

Sloganeering and mudslinging are no alternative to the lack of delivery experienced by ordinary Namibians.

Those who have let them down deserve to be punished at the ballot box.

But those considered as potential alternatives ought to earn the trust of the people.

What has emerged so far suggests there is little which is convincing in terms of nourishing hope for something better.

Sadly so, there seems to be one issue which unites most if not all parties.

It is the exclusion of a minority and the denial of their rights, even if the Supreme Court, in a principled ruling, confirmed these.

But if homophobia is cultivated as a central issue to attract voters, Namibia has not left its discriminatory past behind.

Today’s tune still carries a divisive melody. It betrays the slogan of “unity in diversity”.

It appeals to prejudices and intolerance to attract support, rather than promoting human rights as the guiding principle proclaimed during the struggle for independence.

Not only apartheid violated human rights. Other forms of discrimination also do.

As the famous trade union motto on solidarity declares: “An injury to one is an injury to all”.

More Of The Same?

The ‘new’ in Namibian electioneering seems to be transmitting much of the old.

Promises, fake news, misrepresentations, memory failure and gospels are preaching discrimination.

However, populist rhetoric does not compensate for a lack of vision.

Party programmes barely offer a coherent socio-economic strategy to elevate the country from the bottom of one of the most unequal societies.

They do not take a stand on providing civil liberties for all.

Campaigns resort to insinuations, accusations, namecalling and other forms of bad-mouthing, culminating in hate speech.

Portraying competitors as worse does not mean one is a good alternative.

This must be earned by convincing programmes and constructive arguments, which pass a reality check.

Many misunderstand the new political plurality as evidence that there is a seismic shift looming in Namibian politics. One should not be misled.

When it comes to Namibian political realities, even the Bible can err.

As 2 Corinthians 5:17 states: “The new creation has come: The old has passed away; behold, the new has come.”

No, it hasn’t arrived in Namibia’s political culture. What can be expected is more of the same.

Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci seemed much closer to the reality Namibians are witnessing these days.

As he observed in his ‘Prison Notebook’: “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.”

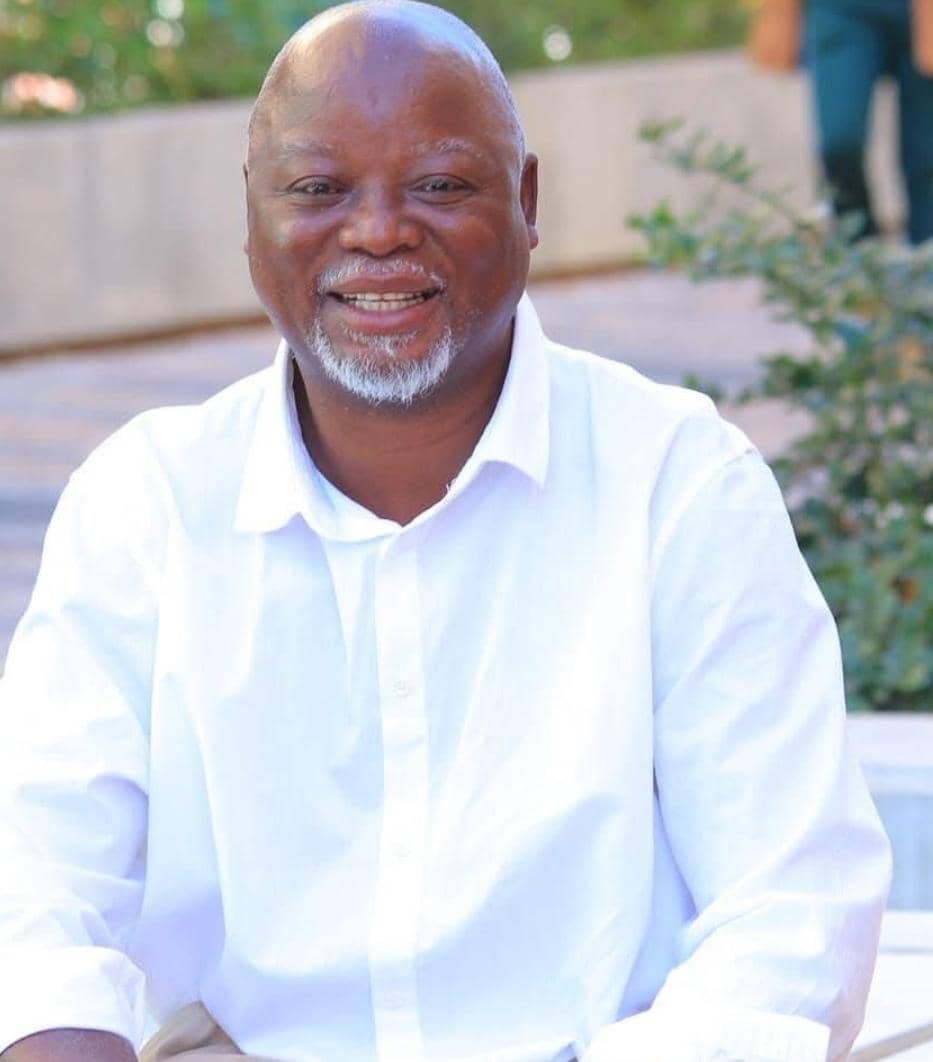

– Henning Melber has been a member of Swapo since 1974

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!