Namibia has a mother tongue dilemma when it comes to the education system. It revolves around the language of instruction in schools, with arguments both for and against using indigenous languages as a medium of instruction.

This dilemma has proved a persistent challenge, with implications for academic achievement, cultural preservation, and national identity.

Namibia is a multilingual nation with various recognised languages spoken by its diverse population, including indigenous languages such as Oshiwambo, Otjiherero, Damara and Nama, among others.

However, the official language of instruction in schools has been English since independence from colonial rule in 1990.

This policy was established to promote unity and facilitate communication in a country with linguistic diversity.

Proponents of indigenous languages as a medium of instruction argue that it promotes cultural preservation and encourages academic success.

According to research conducted by Nekomba (2017), pupils taught in their mother tongue have a better understanding of the curriculum and are more likely to succeed academically.

Further, using indigenous languages in education is seen as a way to preserve Namibia’s rich cultural heritage, as language is an integral part of a community’s identity and serves as a conduit for passing down cultural knowledge and values (Shivute, 2015).

Proponents also argue that it can improve literacy rates among Namibia’s indigenous populations.

Many Namibian children, particularly in rural areas, struggle with English as a second language, which can hinder their ability to succeed in their studies.

Using mother tongue languages can bridge this gap and ensure that pupils have a solid foundation in their first language before transitioning to English (Hauptfleisch, 2018).

COMPLEXITIES

Opponents of indigenous languages as a medium of instruction argue it can hinder pupils’ ability to compete globally and limit their access to higher education and job opportunities.

They argue that English, as an international language, provides Namibians with the necessary skills to compete in the global job market and engage in international trade and diplomacy (Kapenda, 2019).

Additionally, opponents believe that using indigenous languages can lead to a lack of standardisation and quality control, as there may be variations in dialects and writing systems among indigenous languages (Nujoma, 2016).

The government has recognised the complexity of this issue and has made efforts to address it.

In 2018, the education ministry introduced a policy allowing indigenous languages as a medium of instruction in the early grades, with a gradual transition to English as pupils progress.

The aim is to strike a balance between cultural preservation and academic success.

However, challenges remain in its implementation, including the availability of teaching materials, teacher training, and infrastructure in rural areas.

In conclusion, the mother tongue dilemma is a multifaceted issue with implications for language, culture, and education.

As Namibia continues to navigate this complex issue, it will require careful planning, stakeholder engagement, and evidence-based approaches to ensure that the education system meets the needs of all Namibian pupils, while preserving the country’s rich linguistic and cultural diversity.

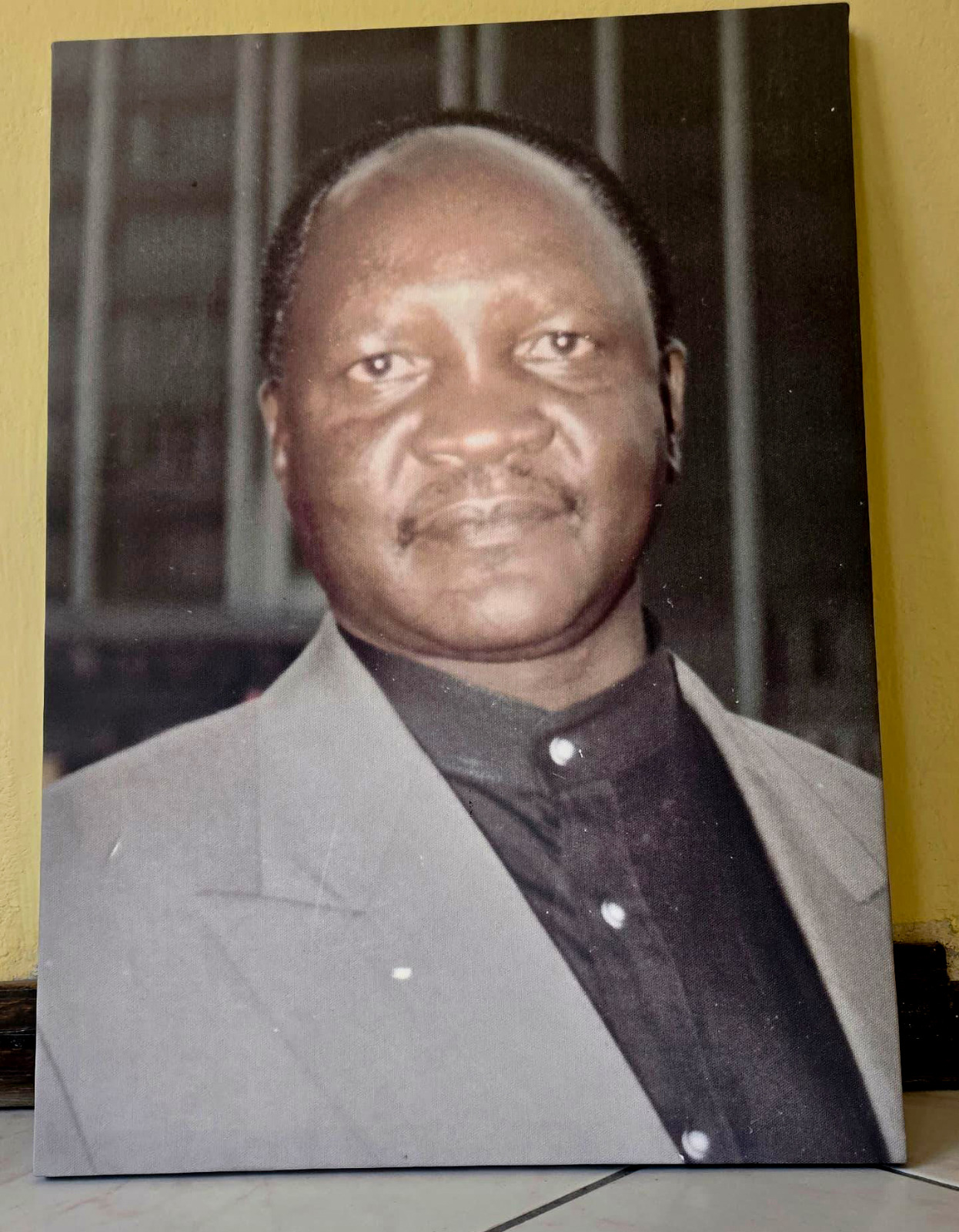

- Annanias Davis Sibeso is a teacher in the Oshikoto region, and has formerly served as a Nanso office-bearer.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!