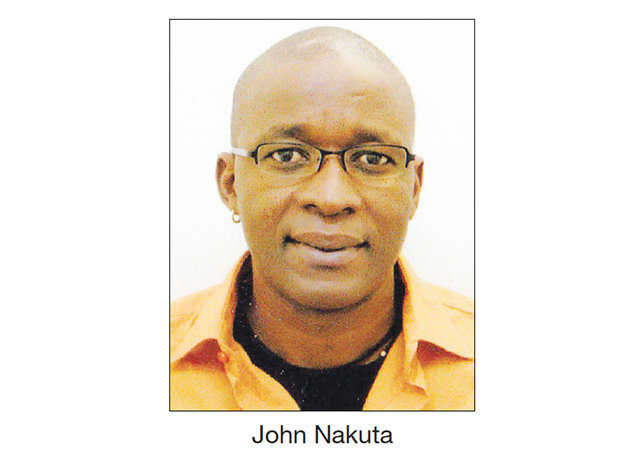

JOHN NAKUTAUNDER ARTICLE 32 (5)(c) of the Namibian Constitution, the president is empowered to appoint eight non-voting members to the National Assembly by virtue of their special expertise, status, skill or experience. On 22 April 2021, the nation learned that president Hage Geingob invoked this power to appoint Patience Masua as a member of the National Assembly to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Peter Hafeni Vilho.

The appointment was not well received in certain quarters. Specifically, the Swapo Party Youth League (SPYL). The merits or demerits of the appointment is territory this opinion piece will not venture into. To do so would divert from the real problem, Article 32 (5)(c) itself!

Namibian legal culture displays a tendency to concentrate vast discretionary powers in institutions, functionaries and officialdom.

Article 32 (5)(c) is an apt manifestation of that. It gives the president powers of appointment without accompanying guidelines on the proper exercise of this power. That is problematic and unhealthy. It potentially enables a president to select appointees based on self-interest or political motivation.

The granting of broad discretionary powers without accompanying clear criteria, to echo the language of the Namibian Supreme Court, opens the article to potential abuse. In this context, in its Medical Association of Namibia ruling, the Supreme Court stressed that where wide discretion is conferred upon a functionary, guidance should be provided as to the way those powers are to be exercised. Article 32 (5)(c) fails to do so.

Countries such as Rwanda, Burundi, Kenya and Zimbabwe have similar constitutional provisions which are strikingly different from that of ours. To begin with, their special seats schemes apply to both houses of parliament unlike ours which only applies to the National Assembly.

Secondly, these seats are filled through an electoral process conducted by their respective electoral management bodies. These provisions are formulated to promote the representation of marginalised groups in their respective parliaments. These marginalised groups variously include women, youth, persons with disabilities, workers, and indigenous people. Such progressive and transformative phrasing is sorely absent from the language of Article 32(5)(c).

It is common knowledge that Article 32 (5)(c) was one of the provisions targeted for amendment in 2014. The ruling elite used the opportunity to increase their seats around the legislative table instead of using it to achieve greater representation of marginalised groups in parliament. Also, nothing was done to make the selection and appointment of such members more transparent, inclusive and democratic. The anti-democratic tenets of Article 32(5)(c) are accordingly still intact.

It serves the political elite to retain it in its current form. What incentive is there for them to amend it in a manner more representative and inclusive? Change, to paraphrase Martin Luther King Jr, is never given voluntarily by the ruling elite, it must be demanded by the people.

By way of illustration, in South Africa it took Chantal Revell, a descendant of the Khoi and San royalty to successfully challenge the use of the political party proportional representation system as the exclusive voting mechanism for electing members of the national assembly and provincial legislature in that country.

On 11 June 2020, the South African Constitution Court agreed with her assertions that the political party list system cannot be seen as the alpha and omega of the proportional representation system required by the South African Constitution. Accordingly, the South African parliament was given 24 months to amend the electoral scheme in a manner that combines political party list representation and independent candidates in time for the 2024 general elections for members of parliament.

The Chantal Revell challenge resolutely reaffirms that the people are their own liberators. Unless we the people demand that Article 32 (5)(c), and by extension the preferential political party list system be amended in a way that is more transparent, inclusive and democratic, we will continue to bicker and fight amongst ourselves for the crumbs falling from the legislative table.

*

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!