They are known as Israel’s eyes on the Gaza border.

For years, units of young female conscripts had one job here. It was to sit in surveillance bases for hours, looking for signs of anything suspicious.

In the months leading up to the 7 October attacks by Hamas, they did begin to see things: practice raids, mock hostage-taking, and farmers behaving strangely on the other side of the fence.

Noa, not her real name, says they would pass information about what they were seeing to intelligence and higher-ranking officers, but were powerless to do more. “We were just the eyes,” she says.

It was clear to some of these women that Hamas was planning something big – that there was, in Noa’s words, a “balloon that was going to burst”.

The BBC has now spoken to these young women about the escalation in suspicious activity they observed, the reports they filed, and what they saw as a lack of response from senior Israel Defense Forces (IDF) officers.

We have also seen WhatsApp messages the women sent in the months before 7 October, talking about incidents at the border. To some of them it became a dark joke: who would be on duty when the inevitable attack came?

These women were not the only ones raising the alarm, and as more testimony is gathered, anger at the Israeli state – and questions over its response – are mounting.

The BBC has spoken also to the grieving families who have now lost their daughters, and to experts who see the IDF’s response to these women as part of a broader intelligence failure. The IDF said it was “currently focused on eliminating the threat from the terrorist organisation Hamas” and declined to answer the BBC’s questions.

“The problem is that they [the military] didn’t connect the dots,” a former commander at one of the border units tells the BBC.

If they had, she says, they would have realised that Hamas was preparing something unprecedented.

Shai Ashram, 19, was one of the women on duty on 7 October. In a call with her family, where they could hear gunshots ringing in the background, she said there were “terrorists in the base and that there was going to be a really big event”.

She was one of more than a dozen surveillance soldiers killed. Others were taken hostage.

As Hamas attacked, the women at Nahal Oz, a base about a kilometre from the Gaza border, began to say goodbye to one another on their shared WhatsApp group.

Noa, who was not on duty and was reading the messages from home, remembers thinking “this is it”. The attack they had long feared was now actually happening.

Because of the locations of their bases, the women of this military unit – known as tatzpitaniyot in Hebrew – were among the first Israelis that Hamas reached after rampaging out of Gaza.

‘Our job is to protect all residents’

The women sit inside rooms close to the border, staring for hours every day at live surveillance footage captured by cameras along the high-tech fence, and balloons that hover over Gaza.

There are several of these units next to the Gaza fence, and others at different positions along Israel’s borders. They are all made up of young women, aged in their late teens to early 20s. They do not carry guns.

In their free time, the young women would learn dance routines, cook dinners together, and watch TV programmes. For many, their time in the military was their first time living away from their families, and they describe forming sisterly bonds.

But they say they took their responsibilities seriously. “Our job is to protect all residents. We have a very hard job – you sit on shift and you are not allowed to squint or move your eyes even a little. You must always be focused,” Noa says.

An article published by the IDF in late September lists the tatzpitaniyot alongside Israel’s elite intelligence units as those that “know everything about the enemy”.

When the women see something suspicious they log it with their commander and on a computer system to be assessed by more senior officials.

Retired IDF Maj Gen Eitan Dangot says the tatzpitaniyot play a major role in “pushing the button that says something is wrong”, and that concerns they raise with a commander should be passed up the chain “to create an intelligence picture”.

He says the look-outs provide key “pieces of the puzzle” in understanding any threats.

In the months leading up to the Hamas attacks, senior Israeli officials gave public statements suggesting that the threat posed by Hamas had been contained.

But there were many signs along the border that something was very wrong.

In late September, an observer at Nahal Oz writes in a WhatsApp group of friends in the unit: “What, there is another event?”

A reply quickly follows by voicenote: “Girl, where’ve you been? We’ve had one every day for the past two weeks.”

The look-outs we speak to describe a range of incidents they observed in real-time in the months before 7 October, leading some to have concerns that an attack was coming.

“We would see them practising every day what the raid would look like,” Noa, who is still serving in the military, tells the BBC. “They even had a model tank that they were practising how to take over.

“They also had a model of weapons on the fence and they would also show how they would blow it up, and co-ordinate how to take over the forces and kill and kidnap.”

Eden Hadar, another observer from the base, remembers that at the start of her service, Hamas fighters were doing mainly fitness training in the section she looked over. But in the months before she left the military in August, she noticed a shift to “actual military training”.

At a different base along the border, Gal (not her real name), says she was also watching as the training increased.

She watched, via surveillance balloon, as a replica model of an automated Israeli weapon on the border was built “in the heart of Gaza”, she says.

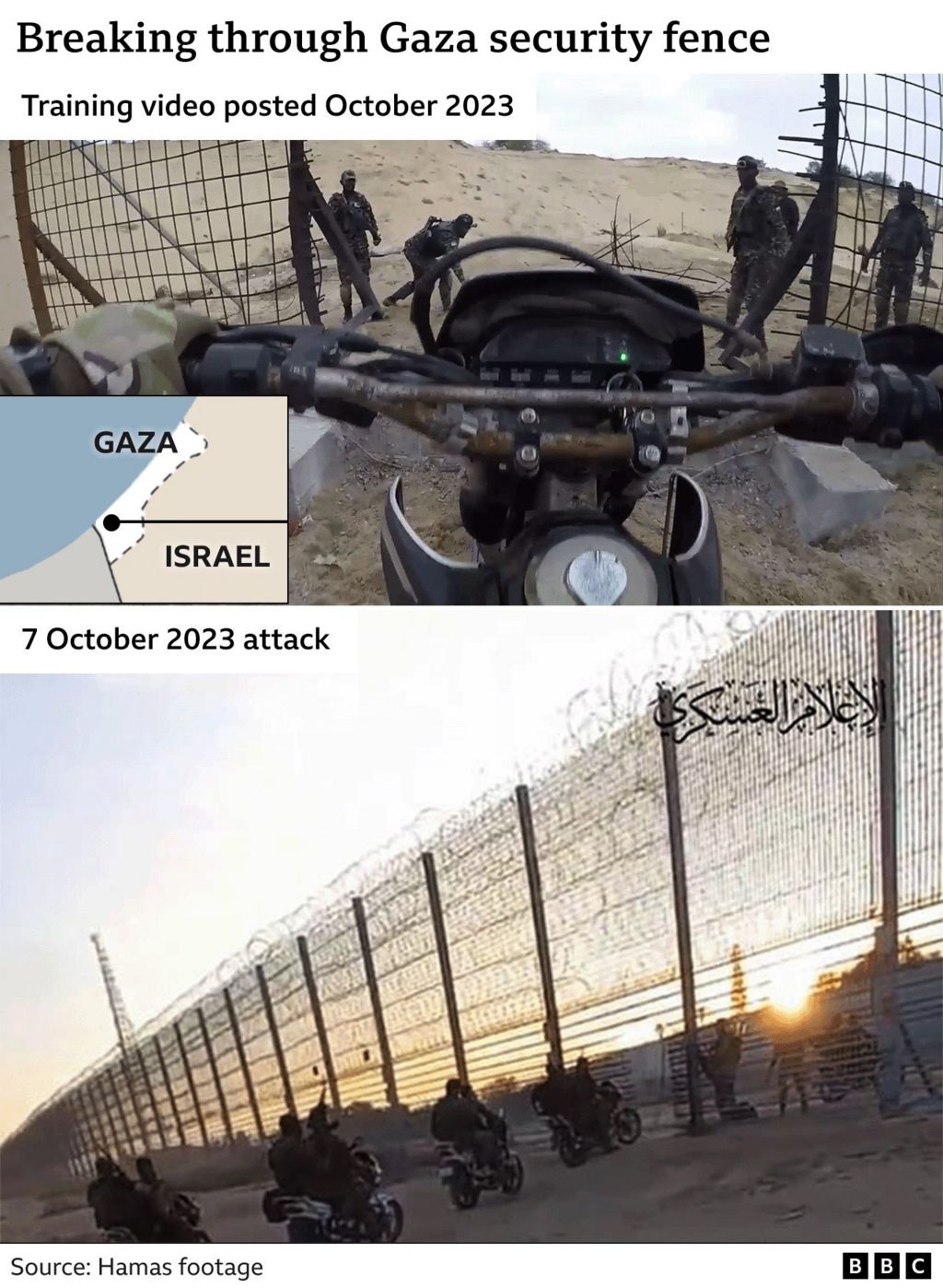

Several women also describe bombs being planted and detonated near the fence – known as Israel’s Iron Wall – seemingly to test its strength. Footage from 7 October would later show large explosions before Hamas fighters race through on motorbikes.

For former observer Roni Lifshitz, who was still in service but not working when Hamas attacked, the most concerning thing she saw in the preceding weeks was the regular patrol of vehicles full of Hamas fighters, which would stop at watch posts on the other side of the fence.

She remembers the men “talking, pointing at the cameras and the fence, taking pictures”.

She says she was able to identify them as being from Hamas’ elite Nukhba Force because of their clothing. Israel has said this was one of the “leading forces” behind the October attacks.

Roni’s account matches that of another woman at the base who spoke to the BBC.

Some of the watchwomen also speak of growing incidents of attempted incursions.

Messages shared with us by one female soldier make reference in code to vans along the border, as well as to the IDF stopping people trying to cross into Israel, which she says was happening more frequently. Members of the unit congratulate each other on these interceptions with heart emojis and GIFs.

In a message observer Shahaf Nissani sent to her mum in July, she writes: “Good morning mummy. I finished a shift now and we had an [attempted border incursion] but this event was really nerve wracking… like it was an event that no one had ever encountered.”

The women also started to see strange changes in patterns of behaviour along the border.

Gazan farmers, bird catchers and sheep herders began moving closer to the border fence, they say. The look-outs now believe these men were collecting intelligence ahead of the attacks.

“We know each one by face and know exactly their routine and hours. Suddenly we started seeing bird catchers and farmers we don’t know. We have seen them move to new territories. Their routine has changed,” says observer Avigail, who requested anonymity to speak out over what she saw.

Noa also remembers them getting “closer and closer” to the fence.

“The birders would put their cages right on the fence. It’s strange because they can put the cage anywhere. The farmers would also go down right next to the fence in an area that is not agricultural and there is no reason other than to gather information about the system and see how they can pass it. It seemed suspicious to us,” she says.

“We talked about it all the time.”

Not everyone we spoke to had been aware of the significance of what they were observing.

Hamas was always training for an attack, and some of the women didn’t anticipate that it was preparing for anything on the scale of 7 October, one said.

Several watchwomen who did fear a major attack was coming have told the BBC they felt their concerns were not being listened to.

When she noticed the vans on the border, Roni says the protocol was to alert her commander and then to keep watching until the vehicles were no longer in her section. She would then file it in a computer system where it would be “passed on”.

But, she says, she has “no idea” where these reports actually went.

“Probably to intelligence but whether they do something with it or not, I don’t really know,” she says. “No one gave us an answer back about what we had reported and conveyed.”

Noa says she couldn’t count how many times she had filed reports. Within the unit, everyone “took it seriously and would pass it on but in the end they [people outside of the unit] didn’t do anything about it”.

Avigail says that even when senior officials came to the base “no-one would talk to us or ask our opinion or tell us a little about what was going on”.

“They just came, gave a task and left,” she says.

‘Why are we here if no-one’s listening?’

As a commander at her unit, Gal says observers would pass information to her which she then passed to her supervisor.

But she says that while this was included in “situation assessments” – when higher-ups at the base would discuss the reports filed by the observers – nothing seemed to be done beyond that.

Several of the women say they voiced their frustrations and worries with their families.

Shahaf’s mother, Ilana, remembers her saying: “Why are we here if no-one’s listening?”

“She told me that the girls see that there is a mess. And I asked, ‘Are you complaining?’

“And I don’t exactly understand the army, but I understood that it’s not the base, it’s the ranks above” that needed to take action, she says.

But despite Shahaf’s worries, her family, like others, had full confidence in the army and the Israeli state, and believed that even if something was being planned, it would be dealt with quickly.

“In the last months she said again and again there will be a war, you will see. And we laughed at her for exaggerating,” Ilana recalls, taking deep breaths between words.

Shahaf was among the first people to be killed on 7 October, when Hamas overran Nahal Oz.

It would come to be the deadliest day in Israel’s history, with some 1,300 people killed, according to the prime minister’s office, and 240 taken hostage.

Air and ground assaults launched by Israel in response to the attacks have gone on to kill more than 23,000 people in Gaza, according to the Hamas-run health ministry.

While they did not know it at the time, the tatzpitaniyot were not the only ones raising concerns, and their observations were not the only intelligence that something was coming.

According to a report in the New York Times, a lengthy blueprint detailing Hamas’s plans had been in the hands of Israeli officials for more than a year before 7 October, but was dismissed as aspirational.

A veteran analyst in Israel’s intelligence agency Unit 8200 warned three months before the attacks that Hamas had conducted an intense training exercise that appeared similar to that outlined in the blueprint, but her concerns were brushed off, the newspaper reports.

The drills conducted by Hamas and other armed groups had also been posted publicly on social media, as seen in this BBC investigation.

The women ‘didn’t get attention they should have’

“The signs were bubbling,” says retired Maj Gen Eitan Dangot. “When you collect all the signs, you would make an earlier decision and do something to stop it.

“Unfortunately this is something that was not done.”

He says that while a full investigation has not yet been conducted, it is clear that the reports from the watchwomen “didn’t get the attention they should have”.

“Sometimes it has to do with the self-confidence of senior officers… ‘OK, I hear you, but I know better than you. I have the experience. I am older than you. I have the strategic picture, and it cannot be what you are telling me,’ for example.

“Or sometimes it can also be chauvinism,” he says.

“In intelligence, you have to sit at a round table and collect information and then build your puzzle. With these people, when you want to know what’s really going on, you have to sit with them, to listen carefully to what they are telling you, what is their way of analysing it.”

Brig Gen Amir Avivi, former deputy commander of the Gaza division, does not believe sexism was a factor, but agrees that more should have been done to address the lookouts’ concerns.

“I cannot say for sure exactly what happened but I can say what is expected,” he says.

“What is expected is that when people on the border do their job and they have concerns and they see things that need to be looked at and assessed, you need to listen. Because they are the professionals. They are the ones who are really the eyes of the battalion and the brigade and the division.”

He says the “biggest failure” was the “assumption that they [Hamas] are deterred” – the assumption that “yes they’re training, yes they have a plan but they’re not going to execute it”.

The IDF has promised a future investigation, and responded to BBC requests by saying: “Questions of this kind will be looked into at a later stage.”

The observers have different opinions about why their reports didn’t get a bigger response, but Avigail shares the view of several we spoke to: “It’s because we are the lowest soldier in the system… so our word is considered less professional.”

“Everyone saw us only as eyes, they don’t see a soldier,” says Roni.

Three months after the attacks, the surviving tatzpitaniyot and grieving families of those killed are struggling to come to terms with what happened as they wait for an investigation.

In Shai Ashram’s bedroom, military berets are hung on a dressing table, upon which there are drawings and photos of her dressed in uniform.

Her dad, Dror, says he sometimes walks into the room and cries.

“She loved her job very much. She loved the army and she loved being a soldier,” he says.

“I’m a taxi driver and I pick up people from the train station and when I see a soldier whose father is picking her up, it hurts me. I’m jealous.”

‘It is with me everywhere’

At her own family home, Noa looks every day at old social media videos of her friends singing and dancing at the base. She sleeps on the sofa every night, afraid to be on her own in her bedroom.

“It is with me everywhere – in nightmares and thoughts, in lack of sleep and lack of appetite,” she says. “I am not the same person I was.”

Scrolling through the WhatsApp chat she shared with other tatzpitaniyot, she points at their names, saying “killed” or “kidnapped”.

At her base, Nahal Oz, the room where the tatzpitaniyot worked now lies in ruins, and the screens they looked through as Hamas prepared for its attack are burned and blackened.

As Hamas surged through Nahal Oz, they killed dozens of people.

Among the dead are many of the women who watched the border so closely for the Israeli state, and who had dared to fear – despite knowing the immense might and resources of Israel – that something like this might one day happen.

Additional reporting by Idan Ben Ari.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!