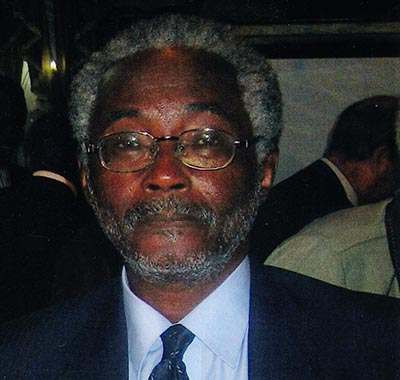

“PAN-AFRIKANIST Bankie Foster Bankie has died. His comrades are quiet. Not even a tribute.”

This was the text message sent to me by one furious comrade of Bankie Foster Bankie, precisely at 12h58, Monday, 14 August 2017. Those simple, yet powerful lines struck me. My mind raced back in time to quickly recall many historical figures who lived on this earth, imparting wisdom.

It reminded me of towering organic intellectuals such as WEB du Bois, William Sylvester Padmore, Kwame Nkrumah, Dani Nabudere, Toussaint L’Ouverture, kaptein Hendrik Witbooi, chief Hosea Kutako, king Cornelius Goreseb and kaptein Hermanus van Wyk.

Bankie F Bankie was one of those men. Bankie understood in meaning and in deed what being an African meant. He understood the importance of Pan-Africanism as a means to unite both Africans on the continent and in the diaspora. This was felt in his work every day.

His idea of unity did not only concentrate on continental unity, as is the preoccupation of the current African Union (AU).

Bankie at the time of his death was preoccupied with some work at the Pan-African Institute for the Study of African Society (Paisas) with former cabinet minister, Nahas Angula.

Bankie was more than just a theoretician. He was a philosopher, an educationist, a historian, a father and a guide.

For many of us, he symbolised resistance, resilience, tenacity and unrestricted belief in the cause of Pan-Africanism. Today, we can confidently claim that Bankie had given his all for the African cause, which cause included mentoring, coaching and teaching future African personalities who shall continue the task of African unity and advancement.

He was a selfless man, and shared whatever little resources he had with others. For him, every occasion was an opportunity for a lesson. I am reminded how he summoned myself and Bernadus Swartbooi to his house in 2010. Professor Kwesi Kwaa Prah, the great African personality, had visited him.

He seized that opportunity, and thought we could learn a great deal from his wisdom. You see, Kwesi Kwaa Prah is a mobile African encyclopaedia. He is a living museum. He is a walking library.

To have spent those few hours in their company enriched our lives for sure. The one thing that is elusive to us all is the tenth Pan-African Congress (PAC).

Bankie, and many others who departed before him, did not really see Africa through the prisms of Western civilisation like Dani Nabudere.

Bankie, and I would want to believe Nabudere, were not ethno-philosophers, nor did they subscribe to African mythologies and falsehoods to propel themselves.

Bankie did not spend much time to interrogate how and what an African should be. His template was African unity at all costs necessary.

I wonder sometimes how Kwame Anthony Appiah would have categorised Bankie had he known him.

For Appiah, Cheik Anta Diop is nothing but an Egyptianist choosing to root African modern identity in an imaginary history, which requires us to see the past as the moment of wholeness and unity, much like a fancied past of shared glory; Blyden, Crummell and Du Bois, collectively as racialists and racists against Africa as a shared metaphysics of Wole Soyinka (Appiah, In My Father’s House).

In essence, Appiah characterises the whole Pan-Africanism movement as nothing else than a racial project advocated by racists.

He does this so with such simplicity: “Pan-Africanism inherited Crummell’s intrinsic racism … we can see Crummell as emblematic of the influence of this racism on black intellectuals, an influence that is profoundly etched in the rhetoric of post-war African nationalism”

Much less, Bankie and many of us couldn’t be bothered by such characterisations. The work must be done.

For him, it was a path of permanent revolution.

For example, in Namibia, Bankie’s work speaks volumes. He engineered with the Pan-African Students Society of the University of Namibia the hosting of the conference on ‘The African Origin of Civilisation and the Destiny of Africa’ on 24-25 May 1999.

This was a historical conference in post-colonial Namibia, which culminated in the birth of the Pan-Afrikan Centre of Namibia (Pacon).

This partly resulted in the personality cult of former President Sam Nujoma with the million dollars’ loss-making movie produced based on his autobiography, ‘Where Others Wavered’.

Bankie also spearheaded various discussion forums in Namibia.

He spearheaded the convention of students at the University of Namibia in 2005 for a conference on ‘Pan-Africanism -strengthening the unity of Africa and its diaspora’, under the 17th All African Students Conference (AASC). These conferences are a long-held tradition of conferences which are held at different universities across the world. The essence is that it brings together students from Africa and its diaspora.

For the first time, after 16 years, it was held in Africa at the University of Namibia. It is critical to acknowledge undoubtedly that Bankie Foster Bankie provided me personally all the ammunition that I could today claim to know a bit on African history. He provided me from time to time with valuable books on Pan-Africanism, and served as a critical link with the outside world. Last time we met, he gave me a Paias handbook and a pamphlet.

With the fossils and dinosaurs of the liberation movements still trying to play a ‘role’ in the new Africa, it is nothing but blocking the vision for the next generation of Africans.

Sometimes, African leaders do not understand what it means to ‘tjaila’.

Kleptocracy and oligarchy have overtaken the dreams of Pan-Africanism on the continent.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!