An election year with intense competition and fierce campaigning needs measured behaviour.

When the dominance of a former liberation movement is waning, political opponents risk violating the norms and principles of a constitutional democracy.

But efforts to minimise such risks should not abandon core democratic values.

They should not restrain constitutionally guaranteed principles such as freedom of opinion and speech.

These are individual rights to which scholars and students are also entitled. If academic freedom and civil liberties are sacrificed on campus as some kind of collateral damage, the price is too high.

The recent prohibition of political activities on the University of Namibia (Unam) campus misjudges the role of institutions of higher learning and patronises staff and students.

INTERNATIONAL SOLIDARITY

In the early 1960s, South African activist Neville Alexander studied at the University of Tübingen in Germany.

On returning to South Africa, the apartheid regime imprisoned him for political reasons. Students at Tübingen mobilised for his release.

The campaign, supported by academic staff, achieved his temporary release. It was the first step towards a West German anti-apartheid movement.

Alexander later became one of South Africa’s most renowned academics.

Inspired by Frantz Fanon’s ‘The Wretched of the Earth’, universities in Western democracies became the cradle of so-called Tiersmondisme (Third worldisms).

Student protests in the US, West Germany, France, the UK and elsewhere culminated in organised protests against the war in Vietnam.

Politics on campus also supported the liberation struggles in southern Africa. Students and scholars alike created public awareness to end large-scale human rights violations under settler-colonial minority rule.

South African universities were the cradle of the Black Consciousness movement.

Steve Biko, like many other students and scholars, including Rick Turner, paid for his activism with his life.

SCHOLAR ACTIVISM

Scholars are at times also public intellectuals and political activists.

Without value-based scholarship, there would have been no Russell Tribunal investigating American war crimes in Vietnam.

The British philosopher Bertrand Russell, American Noam Chomsky, the Palestinian Edward Said, Tanzania’s Issa Shivji, Guyana’s Walter Rodney, Zimbabwean John Makumbe, South Africans Archie Mafeje and Rick Turner, and Nigeria’s Claude Ake are but a few prominent examples.

They personify a dedicated combination of scholarship and political engagement, fighting injustices guided by humanism.

They are testimony that living certain values and insights require leaving academia’s ivory tower.

Such commitment informs teaching, writing and speaking, guided by one’s accumulated knowledge.

Notably, this is not only the privilege of those committed to promoting human rights.

It also allows scholarly proponents of oppression and discrimination, of apologetic colonial reasoning and imperialist advocacy, to act accordingly.

It is the price of democracy and the right to speak out. Such opposites underline that scholars are not neutral.

How can one abstain from a personal view when participating on a panel or offering a course on the genocide in South West Africa?

How can teaching and discussing colonialist history remain value free?

How can one take no side when debating or lecturing on racism or other forms of discrimination?

Academic discourse and analysis should be based on facts, but it does not happen in a value-free context without positioning.

Why should scholars and students not be allowed to take sides on campus with the victims of Israel’s war on Gaza? Universities there were destroyed, and hundreds of students and scholars were killed.

Why should student organisations with a party political affinity not be allowed to meet on campus?

Why should scholars not voice their views in public as commentators on policy matters?

THE FICTION OF POLITICAL ABSTENTION

Banning political activities at universities is a form of censorship.

It raises the question: Who holds the power of definition? And who controls those doing the policing, thereby executing a political act?

How does one deal with university staff (administrative or academic) as members or even activists of a political party?

Why should a university prevent scholars (or students) from using their freedom of expression in public debate? Do they have to wear a muzzle?

If rigorously applied, the fiction of a sanitised, non-political university would require further steps to secure at least some degree of credibility.

It should not have political office-bearers holding positions – including the chancellor, for a start. Nor should it dish out honorary doctorates to politicians left, right and centre.

Trying to impose political abstention is a flawed approach. It stifles intellectual exchange and debate.

Universities are a political arena. Only the degree of liberties or limitations varies.

Academia needs freedom to evolve to its best. A university must offer space for creativity and innovation.

It should not impose a mental straightjacket, restricting constitutionally defined limitations on freedom of speech and civil liberties.

Preventing political activity on campus is not an administrative act – it is repressive, undemocratic politics.

If this is the cost of an electoral year in a democracy, the price is too high.

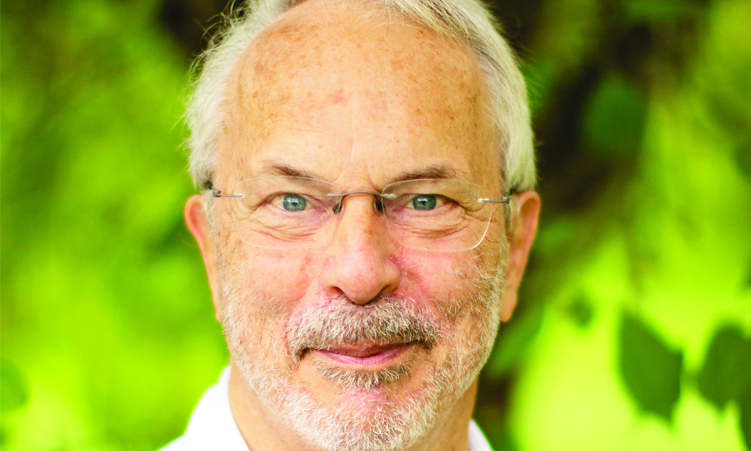

- * Henning Melber studied political science and sociology. He is extraordinary professor at the University of Pretoria and the University of the Free State, a senior research fellow with the Institute of Commonwealth Studies at the University of London, and associated with the Nordic Africa Institute in Uppsala.

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!