Sculptor Wolradt Sithole says luring shapes and forms out of Namibian white marble is an act of listening.

“It gives you a sound. If it goes ding, ding, ding, it’s a hard surface. Choo, choo, choo, it’s soft,” says Sithole. “Those sounds become a song.”

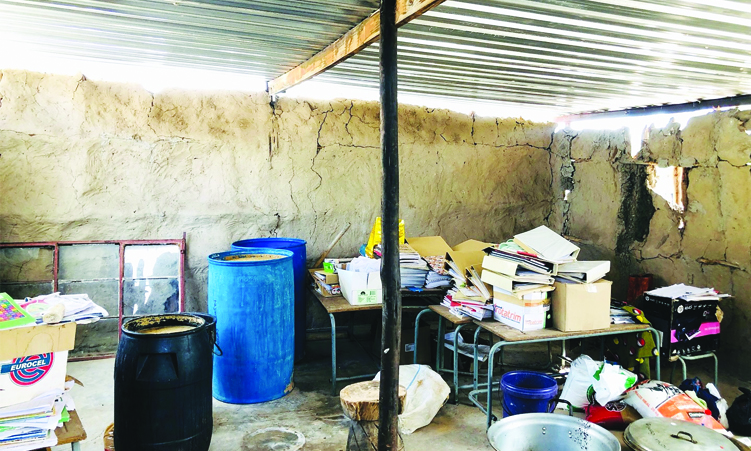

The young artist offers such lyrical insights during a sculpture workshop at Whuda Marble Art Namibia’s large corrugated iron studio in Windhoek’s Northern Industrial area. Across town, at the National Art Gallery of Namibia, ‘Earth to Light’ – Whuda’s otherworldly exhibition of 18 Namibian white marble statues – shines bright against a number of black partitions.

At the exhibition’s opening the previous evening, patrons have been invited to attend a sculpture workshop at Whuda’s studio and a few of them show up bright and early.

Whuda founder Winfried Holze is pleased to see them. He takes centre stage behind a block of white marble, expounding on the history of stone sculpting from the humble, hardworking chisel to the blaring power tools that send white marble flecks dancing across the room.

The white marble is sourced from Karibib and is one of Namibia’s relatively unsung yet sought-after natural resources. Though it’s not as famous as Italian Carrara marble and is primarily used to make tabletops, tiles or terrazzo, Holze hopes to elevate local white marble’s status at home and internationally, particularly in the art world.

An urban designer, city planner and architect by trade, Holze founded Whuda to add value to Namibian marble while transferring his skills as a sculptor and entrepreneur to the young artists who make up the Whuda collective.

Walking around the studio, the work of rising visual art stars Sithole, Kambezunda Ngavee, Isai Kamudulunge Alfeus and William Tonderai Chindoko creates a revolving exhibition that showcases Namibian white marble’s particular allure.

“You see this glowing edge and the sun going through the stone,” Holze says, pointing to a sculpture glistening in the sunlight. “There’s also this glitter. There are two things which are free of charge in Namibian marble. It’s that glitter and the transparency.”

Reimagining the marble offcuts and odd-shaped rejects that Whuda sources from a Karibib quarry, the collective has painstakingly fashioned the smooth souvenir elephants, striking Ovahimba busts, sensual feminine sculptures, abstract art pieces and bittersweet angelic grave stones that enliven the airy studio.

Each iteration speaks to Whuda’s three pillars of production.

“The first pillar is the tourist pillar where we make the elephants and rhinos, small things which a tourist can buy and put in their bag,” says Holze. “They are also kind of to [there] show that there is marble in this country.”

Whuda’s second pillar of production is commission, which has primarily involved sculpting angels and other figures for gravestones. This kind of sculptural adornment is something Holze hopes to drive in Windhoek architecturally.

“I want to introduce art back into architecture, meaning that I want to have sculptures on the buildings,” Holze says. “On the one hand, architecture has lost its soul. It’s four walls, usually square and a roof and a window. What does it give you? Nothing,” he says.

“Yet, if there is a sculpture, it becomes special. Buildings with sculptures on them become national heritage buildings. We have the marble, let’s do our buildings.”

Donning his urban designer hat, Holze also suggests that Namibian white marble be showcased in sculpture gardens and installations dotted around the city.

“As an urban designer, my interest lies in the public spaces, and our public spaces don’t have anything. The tourists coming to Windhoek run away within half an hour because there is nothing here,” he says.

“But imagine if every corner had a sculpture of some sort. It is marble or metal or whatever. Just have a sculpture there and people would come here because of our sculptures. How amazing would that be?”

Whuda’s third pillar of production speaks to their elevation of public spaces and is currently on show in Windhoek at the National Art Gallery of Namibia (NAGN).

“The third portion is the team’s own sculptures, their own expression and artworks,” says Holze.

In the exhibition ‘Earth to Light’, which refers to the land that births the marble and the unique glistening of the white stone, Sithole creates healing meditations in marble inspired by Namibia’s natural heritage of endless valleys, clear moonlight and godly expanses.

“Mostly, I was inspired by nature. Why do you go hiking?” asks Sithole. “When you are going through situations, when you want free space, when you want to think,” he says.

“You look down when you are on top of the mountain and you see the valleys. The river flows. You see the dunes, the sea, the waves. We incorporate these things into these artworks; the curves of the valleys, the stones that have been weathered by our winds.”

Speaking of a spiritual connection and a level of collaboration with the stone’s energy in the creation of his sculptures, Sithole believes Namibian white marble is imbued with the potential for restoration.

“Especially at night-time, you can’t go hiking. So you can use these sculptures as mental therapy,” says Sithole.

“You see these curves, this movement, this dune shape. These stones bring nature into your working environment, your school or home. It gives you light whenever you are in sorrow or in stress. It gives you the mental therapy to say everything will be all right.”

‘Earth to Light’ will be on display at the NAGN until 12 April.

‘Unity’, a sculpture welcoming patrons on the sidewalk outside the gallery, was created during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic by Holze, Kambezunda and Henry Coetzee.

In its celebration of Whuda’s multicultural identity and the diversity of Namibia, ‘Unity’ also refers to the studio’s work in creating an instantly recognisable Namibian art identity, driven by the country’s unique natural resources.

“If you think marble, you think Italy, you think Spain, Greece, and then, if you think about them, you think Michelangelo and the Parthenon and so on. Africa? White marble? You think there is none, it doesn’t exist,” says Holze.

“And yet we have a big occurrence at Karibib. It is being traded as one of the best marbles in the world. But nobody knows it.”

In transforming what is usually used for tabletops, tiles and terrazzo into art, Whuda does well to highlight Namibian white marble as precious, something to be proud of, to own in one’s home and to show the world.

“We need it. We need new inspiration and new hope for our materials. That is what I am in for,” says Holze.

“You must go to the gallery. If you see the guys and the talent that they’ve got, you will see their work is of an international standard,” he says.

“If we can do this in a space of five or six years, what can we not achieve in fifty?”

– martha@namibian.com.na; Martha Mukaiwa on Twitter and Instagram; marthamukaiwa.com

Stay informed with The Namibian – your source for credible journalism. Get in-depth reporting and opinions for

only N$85 a month. Invest in journalism, invest in democracy –

Subscribe Now!